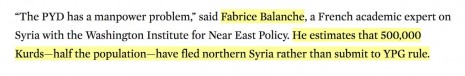

This a response to neocon interventionist Roy Gutman’s two-part hit job smearing the leftist Kurdish resistance in Syria, published in The Nation in February (here and here). Since Gutman’s article was published, his own sources accused Gutman of fabricating their quotes and inventing things that never took place. In one case, Syria expert Fabrice Balanche, took to twitter to call out Gutman for fabricating his quote on why 500,000 Kurds fled northern Syria — Balanche says they fled for economic reasons and due to wars, not because they fled the allegedly repressive rule of the leftist YPG:

Gutman’s misquote:

Balanche responded on Twitter:

Finally, Gutman was forced to retract the quote. But even in something this simple and straight-forward Gutman had a hard time being honest, explaining his fabricated quote as having been “inaccurately compressed”:

I quoted Fabrice Balanche correctly on the numbers who fled, but I inaccurately compressed his estimate into the same sentence as my broader observation. I acknowledge Balanche’s view that most of the refugees fled for economic reasons.

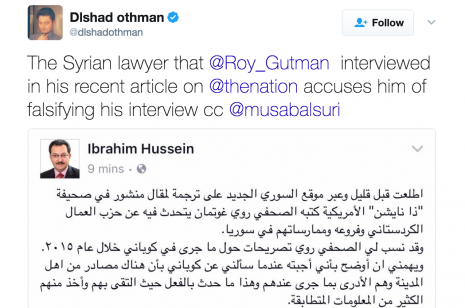

Balanche wasn’t the only one who called out Gutman for fabricating quotes or events.

John Dolan—aka The War Nerd “Gary Brecher” — sent out a special Radio War Nerd subscriber newsletter to respond to Gutman’s hit pieces. He asked to repost it on eXiled Online, open and free to everyone, so that Gutman can’t escape it and everyone who cares knows Roy Gutman’s sleazy game.

I’ve responded to the article in several Facebook posts, but this is important enough to deserve a more formal response. So here it is.

Gutman’s article is a shoddy, dishonest mess, but it will be effective, because the Nation has a better rep than the author’s usual venue, The Daily Beast. So Gutman’s smear will stick, eroding support for the YPG/J, the one heroic faction in the miserable Syrian War.

Gutman didn’t get a six-month grant to write this just for fun. He’s a serious journalistic hit-man.

When Roy Gutman starts writing attack stories, attack aircraft soon follow.

Of course there have been plenty of hit-pieces on the YPG/J before. (I’ll use “YPG/J” for simplicity here, though the YPG/J is now part of a new alliance called “Syrian Democratic Forces,” or “SDF.”)

Some of these marginal reactions were hilarious, as when American right-wingers, infatuated by photos of the women of the YPJ carrying heavy weapons, volunteered — only to discover that they’d joined up with a bunch of socialists who fought under the red flag.

And among those who fly the red flag themselves, there were the inevitable quibbles — mostly by leaders of “movements” with a two-digit membership, seething with rage at this upstart Kurdish militia for being big, successful, and popular. This sort of noise is inevitable. War is a nasty business, and often the combat isn’t the nastiest part.

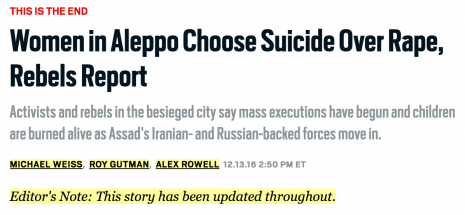

Luckily for the YPG/J, the more sinister elements of the big media were, until now, too busy coming up with stories about atrocities committed by “The Regime” (the Assad government) and its Shia allies to deal with the Syrian Kurds. If you’ve read any Syria stories in The Daily Beast, you’ve seen this kind of atrocity-on-demand reporting, usually bearing the tell-tale byline “Michael Weiss.”

Weiss & co. led the way with reports on the atrocities committed during the “fall” of Aleppo to the Syrian government. If you recall, there were mass rapes,civilians shot on sight, and 250,000 civilians in Eastern Aleppo who would inevitably be slaughtered by “The Regime.”

Except it turned out none of that was true. It was fake news.

There were not hundreds of thousands of civilians in East Aleppo in the first place, largely because the rule of the chaotic, factionalized jihadi militias was so inept that almost all residents got out as soon as they could. Children were not burned alive. There were no mass rapes. It was all lies, produced by journalists nowhere near Aleppo, swallowing and amplifying the sort of hysterical rumor that inevitably accompanies a big defeat and deploying it for the purposes of their patrons: the deep states of Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and above all the United States — all of whom want regime change in Syria at all costs.

Aleppo “fell”; the stories stopped; no burned children’s bodies were discovered, no mass graves were found other than the ones in which Weiss’s (and RoyGutman‘s) “hero jihadis” buried the prisoners they killed. And of course, apologies were not forthcoming. Weiss & co. are not the sort of people to waste time in vain regret, they moved on to the next front in the propaganda war: slandering the YPG/J. The Turkish state was getting more worried about the Syrian Kurds than “The Regime.” Assad’s Alawites are no threat to Turkey, but the YPG/J, with its strong links to the Turkish-Kurdish PKK militia, could become a real problem.

Enter Roy Gutman. He was doing Weiss’s kind of journalism while Weiss was still checking out Barney for possible war crimes. Gutman won the Pulitzer Prize in 1993 for a series of stories on Serbian “atrocities.” Interestingly, both of the 1993 winners of the “International Reporting” Pulitzer won for stories on Serb “atrocities” that turned out to be, at the very least, exaggerated:

“International Reporting:

Roy Gutman of Newsday, Long Island, NY

For his courageous and persistent reporting that disclosed atrocities and other human rights violations in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.”

The stories paid off in the US-led air war against Serbia in 1999 — in that sense they were very successful. They were not, however, especially accurate. The New York Times’ Balkan correspondent, David Binder, wrote that,

“…Gutman’s stories [on the Balkan War], far from representing on-the-scene reporting, were based on scantily identified sources who never surfaced as real people” and that one of Gutman’s key sources “turned out to be using five different aliases.”

Binder sums up Gutman’s work with Orwell’s phrase “Once a whore, always a whore.” So naturally The Daily Beast thus found Gutman the perfect co-author for Weiss for its endless flow of hit-pieces on Syria. When the Beast told its readers that the Syrian Army was committing mass rapes in Aleppo, Gutman and Weiss shared the byline.

When the Turkish state wanted the Kurds softened up in advance of an attack on Rojava (the de facto Kurdish state in Northern Syria), it turned to Gutman, now based in Istanbul.

And Gutman came through in his classic style. Let’s have a look at what he managed to do with his assignment: maligning the YPG/J for The Nation.

The first part has a real grabber of a title, using the time-honored ask-a-question method: “Have the Syrian Kurds Committed War Crimes?”

Gutman concludes, inevitably, that indeed they have. Never mind which crimes; most people will simply pass the headline around on social media. You know how it works. I know, everybody knows: somebody sends you the headline, you get the point, you don’t bother reading the story. So, thanks to Gutman and the editors at The Nation, thousands of naive Twitter and Facebook users will draw the easy, lazy conclusion that the Syrian Kurds are just as dirty as Islamic State, Jabhat Fateh-ash-Sham, or any of the other factions in the Syrian war. They’re all the same, right?

Wrong. If you actually get past Gutman’s headline, his evidence for “war crimes” committed by the Syrian Kurds is remarkably feeble. Given what might be called the ambient level of horror in this war, what’s striking is Gutman can’t even accuse the Kurds of the sort of crimes that have become commonplace among other militias. Have they slaughtered civilians for speaking the wrong language? No. Have they said, as the leaders of most of the Sunni militias have done, that everyone must accept their creed, leave, or die? No.

Gutman’s main claim is that the YPG/J has expelled villagers from their houses and even demolished or burned those houses. That’s possible, though people I know who are serving with the YPG/J deny it. And in the Syrian context, where massacre videos have become old news, mere expulsion and property damage hardly register as “war crimes” at all.

Let’s suppose that, for once, Gutman’s sources are telling the truth. Why would the Kurdish militia expel people or burn their houses? Irregular war is not Gettysburg. When an irregular force occupies a village or town dominated by hostile factions, it has limited options. Faced by harassment sniping or collusion with the former rulers among inhabitants, the irregular force can, and usually does, simply kill those it suspects. The YPG/J doesn’t do that, as even Gutmanimplicitly admits.

So, faced with implacable ethnic or sectarian enmity — in practice, refusal to accept “atheist” YPG/J occupation among devout Sunni Arabs — the Kurds may (or may not) have expelled suspects from occupied villages. That may not be Geneva Rules, but by the standards of irregular war, let alone the standards of Syria over the last four years, it’s the mildest reaction possible.

Gutman also claims that the YPG/J has colluded with the Assad regime to divide up parts of the country, notably Hasakah. Very possible. Again, standard multi-faction war behavior. And very sensible, too, since until recently there was a little problem in that part of Syria called Islamic State that called for collusion, a damned sight more collusion than actually occurred.

Gutman implies that this collusion proves that the YPG/J is a creature of the Assad regime. This is nonsense. The guy needs to watch Game of Thrones, even if he can’t do any more serious historical research in the pattern of endless treachery which defines these wars. Actually, Assad’s “Regime” hates the YPG/J. Assad’s defenders on social media never fail to sneer at the YPG/J’s good reputation, and call people like me “Rojava-heads” while vowing to reconquer every inch of Syria. That vow is addressed to Syria’s Kurds, and is an existential threat (as they say) to Rojava. Any collusion between Assad and the YPG/J was a classic alliance of convenience, as local observers have always realized.

Gutman‘s claims all depend on pretending that irregular war is inherently evil, that there are no rules governing unconventional war. If the YPG/J’s tactics are illegitimate, you’re delegitimizing all irregular war. You’re describing tactics practiced by every irregular leader from Collins to Mandela. You have not found evidence of actions that are considered atrocities by legitimate irregular groups: enslavement, sectarian murder, forced conversion, massacre of prisoners.

That last one, “massacre of prisoners,” is the most significant. If you know irregular war, you know that groups can’t afford to keep POWs in nice neat camps. So most of the time, they try to trade them, or kill them outright. Killing of prisoners has been documented among many groups in the Syrian War.

There’s no evidence, no claim even by Gutman that it’s been carried out by the YPG/J.

To decry the tactics of irregular militias by way of advocating high-tech bombing campaigns is Gutman’s standard MO. It’s also a particularly vile, though lucrative, form of hypocrisy.

Oddly, Gutman takes on the YPG/J’s greatest moment, Kobane — a purely conventional battle where no civilians were involved and where the Syrian Kurdish militia behaved heroically.

But look what that struggle becomes in his hands:

“In late 2014, when ISIS attacked Kobani, drawing US air strikes that killed as many as 2,000 ISIS fighters….[a]ccording to former residents, the YPG abandoned the outskirts of Kobani to ISIS without a fight, ordering residents to leave the villages they were eager to defend.”

Even by Gutman‘s very low standards, this is appalling. He accuses the YPG/J of abandoning outlying villages — a “war crime”, apparently.

Remember the siege of Kobane? Remember the situation in Syria in the winter of 2014-15?

IS was advancing on the little Kurdish border town of Kobane with a huge force, complete with all the heavy weaponry it had inherited from the collapse of the US-funded Iraqi Army. YPG/J was holding out — outnumbered, outgunned by IS, which was coming off a string of remarkable victories and considered unstoppable. After all, the much bigger, better-armed Iraqi Army had just abandoned half of Iraq to a few hundred IS troops.

And now they were closing in on Kobane. Erdogan, whose spies were helping IS, gloated in October 2014 that “Kobane is about to fall.” No one doubted him.

As the huge IS force closed in on the town, YPG/J commanders withdrew to the city, and ordered locals to pull back with them. They told civilians to flee across the border, but they themselves set up defensive positions in the town and prepared to die fighting.

They did die, in huge numbers. Estimates vary, but at least 2,000 women and men of the YPG/J were killed in that battle. But they held on. They held Kobane against that formerly unstoppable IS force, and with US air support killed thousands of those slave-dealing sectarian IS fighters. IS was never the same “unstoppable” force after its defeat in Kobane. (And Turkey began to be concerned about this annoyingly undefeated Kurdish militia on its southern border which had failed to collapse on schedule.)

A great moment, one of the few truly heroic moments in our era. But not for Roy Gutman. Hey, that’s not his assignment. Gutman dismisses the Siege of Kobane with a single paragraph implying that ordering an outnumbered defending force to pull back into a central urban position, against the wishes of “former residents” of those “outlying villages,” is in some way blameworthy. Withdrawing to a central, defensible position is the obvious tactic for an outnumbered defensive force. Oh, and in passing he slanders the thousands of Syrian Kurds killed in the battle with the outright lie that it was the “US air strikes” alone that killed IS attackers, as if the defenders of Kobane somehow failed to inflict a single casualty on IS in the entire long siege.

Gutman’s lack of conscience actually frightens me a little. You’d think he’d avoid talking about the Syrian Kurds’ most heroic moments, like Kobane. Au contraire! In the second part of his Nation piece, snidely titled “America’s Favorite Syrian Militia Rules with an Iron Fist,” he takes on another of the Syrian Kurds’ most heroic actions, the liberation of Sinjar.

Again, it helps if you actually know a little about the context, because Gutman and his editors are hoping you don’t. Sinjar is a town in northwestern Iraq inhabited mostly by the Yezidi, a minority religious sect. IS overran the area in the Summer of 2014. The people of Sinjar were expecting to be protected by the peshmerga militia of the KRG (Kurdistan Regional Government) of northern Iraq. For reasons still not clear, the peshmerga fled and left the Yezidi defenseless (rumor has it that this involves PUK/KDP rivalry within the KRG.)

Islamic State zoomed into Sinjar unopposed. And then, because the Yezidi were “kaffir,” “unbelievers,” Islamic State murdered thousands of civilians, saving only young women. They kept the young Yezidi women and girls alive so they could be sold as sex slaves. Even now, Yezidi women are sold as sex slaves. This is not a wild rumor, unlike Gutman’s tales. Islamic State not only admits the massacre and enslavement, they boasted about it in an article, “The Revival of Slavery before the Hour,” in their glossy magazine, Dabiq.

The fall of Sinjar was one of the worst war crimes — real war crimes — in recent history. And it remained unavenged until the Syrian and Turkish Kurds of the YPG/J and PKK freed the area.

Now, let’s have a look at that horrific story as reported for The Nation by Roy Gutman:

“Turkey is not the only US ally at odds with the YPG. Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government in late December threatened to use force if the PKK didn’t withdraw from Sinjar in northern Iraq, which the KRG insists is in its security sphere. (The PKK had moved into Sinjar in 2014 to fight off an ISIS attack against the Yazidi population there.)”

Did you catch that? For Gutman, the liberation of the Yezidi survivors proves only one thing: The YPG and PKK are troublemakers, unpopular not only with Turkey but the KRG which had abandoned the Yezidi to their fate. He gives one sentence—in parentheses, yet! — to the cause which brought these interlopers to Iraq: “..to fight off an ISIS attack against the Yazidi population there.” Yes, Roy, there was a bit of an attack. A bit of a genocide, in fact, but never mind — it’s not going to help your case, so never mind.

You can see Gutman’s core agenda in this disgusting passage. Gutman’s patron is the Turkish state, and its quarrel with the YPG/J is that it’s too closely associated with the Turkish-Kurdish militia, the PKK. The Turkish military/intelligence state fears that a de facto Kurdish state in Rojava will serve as a cross-border sanctuary for PKK fighters within Turkey.

Months before Gutman’s Nation article appeared, Erdogan’s favorite newspaper, The Daily Sabah — the Fox News of Turkey — published an article accusing the YPG/J of being a tool of the PKK. It would have made (may have made, for that matter) an excellent first draft for Gutman’s piece.

So, if the PKK rather than the YPG/J itself is the real villain of Gutman’s piece, what can we say about the PKK? Gutman makes three points about them:

1. The PKK is listed by some countries as a terrorist group.

2. The PKK is funded by Iran.

3. The PKK and YPG/J are really the same organization.

The third claim, that the YPG/J and PKK are basically the same group, is roughly true. “Roughly” because the history of insurgent groups is full of factional splits among groups that were once united. For the moment, at least, it seems that the YPG/J and PKK share leadership.

And the proper response to this is, “So what?” Which brings us to the big question, the one that Gutmanwill never ask: Why is there a PKK in the first place?Why are Turkey’s Kurds, who make up about a quarter of the country’s population, so angry that they’re willing to undergo the horrors of irregular war against a powerful, ruthless security state, in order to win autonomy?

The treatment of Turkey’s Kurds is an appalling story. Modern Turkey was founded as a mono-ethnic state. Everyone inside it was a Turk. Those who were not (Greeks, Armenians) were killed or expelled. Those remaining inside its borders were Turks — by law:

“A 1924 mandate forbade Kurdish schools, organizations and publications. Even the words ‘Kurd’ and ‘Kurdistan’ were outlawed, making any written or spoken acknowledgement of their existence illegal…[B]etween 1925 and 1939, 1.5 million Kurds, a third of the population, were deported and massacred.

“In 1930 the Turkish Minister of Justice declared, ‘I won’t hide my feelings. The Turk is the only lord, the only master of this country. Those who are not of pure Turkish origin will have only one right in Turkey: the right to be servants and slaves.'”

The Turkish state’s hatred for Kurds has been a constant of modern Turkish history. I’ve talked to ethnic Turks who grew up in the Southeast, watching Kurdish kids’ bodies dragged behind M113s. This mistreatment intensified when a Kurdish-oriented political party, HDP, played a role in Erdogan’s only election setback in 2015.

Since that loss, Erdogan’s AKP party has unleashed the state security apparatus on anyone connected with the HDP or any other Kurdish-oriented politics. The co-mayors of Diyarbakir, the biggest Kurdish city in Turkey, have both been arrested, as have thousands of Turkish Kurds suspected of any link to Kurdish activism. So the next time somebody tells you the PKK “engages in violence, why don’t they try peaceful political means?” — ask them to tell you how many peaceful HDP activists are now in Turkish prisons, where torture is SOP.

Remember, Gutman is a journalist based in Istanbul. He must be familiar with this information. It’s not exactly obscure. But you won’t hear about any reasons for Kurdish discontent in Turkey in his PKK-bashing.

As for Gutman’s second point, the PKK’s “terrorist group” designation — it depends on who you ask. The PKK is an irregular militia, or “guerrilla” organization (which for Gutman means it’s automatically in the wrong, since he fails to recognize any rules operating in irregular war) — but the PKK is actually rigorous in trying to avoid random civilian casualties. This can be demonstrated very simply if you go through the record of bombing attacks in Turkish cities. When they target random civilians, even Turkish authorities know they can safely be attributed to Islamist militias. When they are aimed at Turkish police or soldiers, they are inevitably the work of the PKK.

So which countries say the PKK is a “terrorist” group? Turkey, as you might expect. And NATO, because Turkey is a huge part of NATO’s military power. And the US, which has nuclear weapons stored on Turkish bases. All of which proves nothing. Other groups not dependent on Turkish military support refused to classify the PKK as a terrorist group. The UN does not consider it “terrorist.”

Even the tame US media gets a little confused about why the PKK must be called a terrorist group, as in the Washington Post’s headline: “A US-Designated Terrorist Group Is Saving Yazidis and Battling Islamic State” — one of those headlines that seem to have in implied “WTF!?” in invisible ink at the end.

As for Gutman’s claim that the PKK is funded by Iran, it’s impossible to verify or refute with any certainty. If you were running the Iranian state, you might have an interest in funding insurgent groups which could be employed against troublesome neighboring states (and then betrayed to their security forces when relations improved). That sort of Byzantine treachery has been the Kurds’ fate for decades, and no doubt Iran is playing some murky role in the process even now. But again — so what? Why is “Iranian involvement” somehow prima facie evidence of innate evil, when blatant interference in Middle Eastern wars by other states — the US, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Israel, Qatar, Britain — is taken as natural or even beneficent? Iran is a regional power with its own Kurdish population (which it generally treats better than Turkey has treated its Kurds); as such, it may dabble in Kurdish insurgency. One good way for Turkey to stop that would be to end the reason for the PKK insurgency in the first place: by ending the Turkish state’s monstrous oppression of its Kurdish population.

In short, Gutman’s two-part article is a shockingly dishonest, sleazy and incompetent performance. I wouldn’t have been surprised to see it in the pages of The Daily Beast; they have made it very clear they have no standards in reporting on Syria. The surprise is that it appeared in the pages of The Nation. You expect a little more out of them.

Or at least I did. My mistake. Turns out that some editors there have the same dreary Manhattan-Leftist envy and hatred for a victorious, non-sectarian socialist militia as every other dismal basement Trotsky.

John Dolan (aka “Gary Brecher”) co-hosts the Radio War Nerd podcast with Mark Ames. Subscribe today!

This review was originally published in The eXile on March 30, 2000

After reviewing so many well-meaning, badly-written books, it’s a pleasure to dissect the work of a skilled liar. The liar in question is Leon Aron, the book is Yeltsin: A Revolutionary Life. Aron’s book attempts a task which is, to borrow his favorite Classical allusion, “Augean”: cleaning up the filth-dripping career of Boris Yeltsin.

But though the task is, as he puts it, Herculean, Aron has one tremendous advantage: he is writing for readers who know very little about contemporary Russia. Only an audience deeply ignorant of Russia would stand for a biography of Yeltsin which in 750 pages makes only four brief references to Boris Berezovsky. Writing a Yeltsin biography which ignores Berezovsky is like writing a history of the Nicaraguan Contras without mentioning Oliver North. Yet Aron expects to get away with excluding Berezovsky from his story – and based on the reviews of this book by what passes for the American intelligentsia, he will succeed. Martin Malia has informed the readers of the Wall Street Journal that “whoever wishes to understand post-Communist Russia…must henceforth start with Mr. Aron’s path-breaking book.” The New York Times, gullible as ever, has termed Aron’s book “a fine, full-blooded portrait of Yeltsin.”

Sadly, very few of the readers who buy Aron’s book on the strength of these endorsements will know enough about Russia to see the scope of the Big Lie Aron feeds them. They will end up believing that Yeltsin and his friends were doing God’s work, or at least Adam Smith’s — rather than divvying up the plunder of a fallen empire while its stunned, exhausted people were too busy trying to survive to put up any resistance, and whose hope and faith in a better, more just future had been coapted and perverted by some of the most bloodless, amoral nihilists-posing as free-market democrats-that the world has ever seen. Just taking the loans-for-shares scheme alone — a theft that even the IMF and World Bank have disavowed — it is estimated that at least tens of billions of dollars worth of state assets were literally given away to the oligarchs (and often times even paid for by stealing the unpaid wages of Russia’s state workers and pensioners) for almost free. That alone would qualify Yeltsin as the greatest thief that mankind has ever known.

Aron has so little respect for his American readers that he actually attempts to tell them that the oligarchs aren’t really such a big deal, that they’re largely myth:

“…The secrecy in which the Russian robber barons cloaked their dealings resulted in a vast exaggeration of their wealth and power both by the Moscow rumor mill and by the resident correspondents of Western newspapers and television networks…The truth was further obscured by a deep suspicion of personal wealth…and by self-aggrandizing claims and accusations with which the perennially warring moguls puffed up their worth and which they hurled at one another through their media outlets.”

Aron’s prose slips a bit here, particularly in that last sentence. If the oligarchs are really so marginal, how is it that they apparently own all the “media outlets”? Or is ownership of the electronic media such a minor advantage? Aron simply dismisses other charges against Yeltsin without argument:

“…equally bizarre [is] the ‘theory’ that explained Yeltsin’s dependence on the oligarchs by the gifts which they showered on his family — as if the President of Russia, should he decide to do so, needed intermediaries in raiding the country’s treasury.”

One would like to ask Mr. Aron exactly what is “bizarre” about this “‘theory’.” “Intermediaries in raiding the country’s treasury” is a fairly exact description of the talents of Berezovsky and above all Chubais (whom Aron treats very delicately). It seems less than “bizarre” that Yeltsin, whose job was not to cook the books but to present a “democratic” face to the West while the cooking was in progress, would work with the leading embezzlers rather than carrying sacks of dollars out of the banks. He’s not in that sort of condition.

The one figure of the 1990’s who stirs Aron’s bile is Yavlinsky, the least corrupt of all the “reformers.” Quiz for non-Russian readers: explain why does Aron hate Yavlinsky, of all people, so intensely. In 25 words or less. [HINT: Yavlinsky, as the only authentically democratic, untainted Western-style politician in Russia, and the part-Jewish leader of the fiercest opposition Duma faction, does WHAT to Aron’s central argument that all those opposed to Yeltsin were crypto-fascist/anti-Semitic-Stalinist monsters?]

In whitewashing Yeltsin’s astoundingly sleazy career, Aron leans heavily on his readers’ worship of the free market and the power of the individual to transcend, even remake, the world around him. (In other words: successful Americans.) Playing on the paradigmatic narratives Americans absorb with their morning cartoons, Aron transforms young Yeltsin into a Siberian Abraham Lincoln, growing up in “…the Ural-Siberian tradition of diversity, acceptance and meritocracy.” Yeltsin may not have lived in a log cabin, but as Aron points out, his grandparents did. As a boy, Yeltsin rambles in the woods, explores Siberian rivers and generally gets up to all sorts of Huck-Finn deviltry (blowing half his hand off while playing with a grenade, for example), but grows up to be the hardest-working, straightest-speaking construction boss in the history of Sverdlovsk, a totally (!), incorruptible workaholic who sternly rejects every attempt at a bribe or dubious gift. To give Yeltsin due credit, one must admit that he certainly transcended that provincial prejudice in later life.

Aron is at his best when his knack for hagiography has the fewest obstacles (ie facts) to overcome. This means that his early chapters about Yeltsin’s life in Sverdlovsk are his best. When Boris is summoned to Moscow — his drive and goodness recognized at last — Aron’s task becomes much harder.

Aron has two strategies for wrestling his readers into respecting Yeltsin. First, he uses his early chapters to paint the Soviet system so black that a naive reader will accept any change as an improvement. In the process he makes Yeltsin’s task literally Herculean – and I mean literally: Aron consistently compares Yeltsin’s tasks to the labors of Hercules, above all to the cleaning of the Augean stables. (Though, in a momentary lapse, he fudges a bit by describing Yeltsin as “both Augeas and Hercules” — that is, the man responsible for the mountain of dung, as well as its remover.)

Aron’s not shy about enlisting a plurality of Classical heroes, either. When Hercules tires, enter Sisyphus. Here is Aron’s depiction of Yeltsin after he has been rebuked by the CPSU:

“Yeltsin sat on the dais, motionless, his head in his hands. The monstrous boulder that he, day and night, had pushed up, up, up the steep slope, through briars, his hands cut and bleeding, his knees in muck, his sides bruised and his heart strained – had finally crushed Sisyphus.”

If I may resort to the argot of my native malls: what crap. The torture to which Yeltsin has been subjected is no more than a public scolding by his fellow apparatchiks, to which Yeltsin reacts not by standing up for his rights in Lincolnesque fashion but by groveling, as Aron admits, “like a star defendant of Stalin’s show trials in the 1930’s.” And Yeltsin, when challenged, shows that he can grovel with the best of ’em:

“I am very guilty before the Moscow party organization, very guilty before the GorKom, before the buro, before all of you and, of course, I am very guilty before Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev, whose authority is so high in our country and in the whole world….”

But Yeltsin groveled, not before Stalin but…Gorbachev! It’s no shame to grovel before Stalin — God would grovel before Stalin — but to react to a tonguelashing by his doddering epigones of 1987 vintage, as Yeltsin did, is hardly Sisyphus-level heroic endurance.

Aron’s other strategy for rehabilitating Yeltsin is simple old Russophobia. He says outright that Yeltsin’s opponents are anti-Semitic fascists, and offers several grotesque cartoons out of Zavtra as evidence. In other words, Russians who objected to seeing their jobs, their savings, their country whisked away; who were bothered by the starvation and entropy of the countryside; who found it suspicious that every item of value in the former USSR had passed, somehow, into the hands of a dozen master embezzlers; that all these people were no more than Jew-baiting racists. Now that is what Dr. G. used to call the biiiiiiiiiiig lie. 900 pages of it. Now that’s big.

The only remaining issue for the reader is guessing how big was Aron’s compensation package for producing this shameless encyclopedia of court flattery. We’d bet that it was real big. And judging by the early reviews, it was money well spent.

John Dolan is co-host of the Radio War Nerd podcast. Subscribe here.

This review was originally published in The eXile in April 2004

In a review of several Vietnam memoirs, I asked readers for information on oral histories by Soviet soldiers who served in Afghanistan. Several mentioned this book, Zinky Boys, published in English translation 12 years ago. As far as I know, it’s still the only oral history by Afghan vets available in English.

Zinky Boys is clearly modeled on the many bestselling Nam memoirs. The introduction is written by one Larry Heinemann, a Vietnam vet who visited Russia to talk to Afghan vets. His introduction is the worst thing in the book, full of silly blather about how democracy is sweeping over Russia and how the Afghan vets will no doubt play a part in its victory.

Yet, for all the superficial resemblance to Nam books, Zinky Boys is unlike any American war memoir. The differences are easy to spot, but hard to explain. Some you’d expect: for one thing, the editor can hardly make a point without quoting Dostoevsky, Lermontov, Berdyayev or Tolstoy. You don’t find that sort of literary figure quoted much in the typical Nam memoir. Hendrix is about as close to high culture as they usually get.

A far more radical and intriguing difference is the prominence of women in the book, starting with the fact that the editor is Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian journalist. I can’t think of a single Nam memoir edited by a woman. It may be that Russian women feel entitled to speak about war more freely than American women simply because Russian women took a huge role in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945. In fact, one of the Afghantsi who tells his story here mentions that his grade school was once visited by a WW II vet nicknamed “Mother Sniper,” whose claim to fame was that she had killed 78 Germans during the war. (She scared him so much he was ill for a week.)

But the women who speak here really didn’t enjoy Afghanistan much. As one of them says frankly, “I wanted to be in a war, but not like this one. Heroic World War II, that’s what I wanted.”

Zinky Boys focuses, much more than any Nam memoir I know, on the dead. Even the title refers to the closed zinc coffins in which Soviet dead were sent home. Grieving families were forbidden to open the coffins, and many of the soldiers’ mothers interviewed talk about how awful it was, never knowing whether their dead son was actually in that zinc box:

“They brought in the coffin. I collapsed over it. I wanted to lay him out but they wouldn’t allow us to open the coffin to see him, touch him…Did they find a uniform to fit him?…Now I just want to be in the coffin with him. I go to the cemetery, throw myself on the gravestone and cuddle him ….”

Many of the mothers interviewed went insane after their sons’ deaths: “His mother went mad two days after the funeral. She ran to the cemetery at night and tried to lie down with him.” Does the emphasis on grieving mothers reflect simply the author’s special interest, or does it imply that the mother-son relationship is more important in Russian than American culture? Some of the interviews suggest that this is by far the strongest bond in Russian women’s lives: “Yura was my eldest son. A mother shouldn’t admit it, probably, but he was my favorite. I loved him more than my husband and my younger son.”

Yura’s mother’s story is one of the grimmest in the book, because she blames herself — with some justice — for his death. Theirs was a “good family” in Soviet terms. And like a good Soviet son, Yura enters officers’school, then tells his mother, “All those high ideals you taught me, they don’t exist. Where did you get them all from?” His mother keeps up the lie: “I told him yet again that our Soviet life was wonderful and our people were good.”

Inevitably, Yura ends up dead. And his mother, a born storyteller, tells how she prayed that it was her other son, Gena, who was dead: “I asked them, ‘Is it Gena?”No, it’s Yura,’ one of them said, very quietly.” She tells this story against herself. Now that’s horror.

Not all the women interviewed in Zinky Boys were entirely unhappy in Afghanistan. The Russian proverb, “War is a stepmother to some and a mother to others,” applies even to those women who served. One who volunteered for Afghan duty as a civilian employee has some of the best war stories I’ve ever read. She starts out fending off attempted rape by every officer she meets. (No Afghan women feature in the book in any sexual or romantic context. You get the sense that, unlike US GIs in Vietnam, Russian troops didn’t find the local women attractive — not to mention the fact that, unlike the GIs, the Russian troops were even poorer than the Afghans, making prostitution unprofitable.)

Then she finds a man she likes: “…I found…love? That’s not a word much used over there.” But if it wasn’t love, it was something intense enough to make her shield his body with her own when they come under fire. The narrator boasts that “…when we got back [to base] he wrote his wife about me. He didn’t get any letters from home for two months after that.”

It’s strange how little wives and husbands figure in these stories. Again, I’m comparing these stories in my own provincial, ethnocentric way with the Nam memoirs I’ve read. In those books, if anyone else is mentioned it’s usually the wife or longterm girlfriend. That’s not the case here. There are lovers, who seem to attain, however briefly, the status of mothers in the narrators’ lives. But when those lovers become spouses, they seem to fade into the background; only the mother/son bond remains.

The soldiers’ own stories of combat in Afghanistan don’t seem nearly as vivid as their mothers’ accounts of meeting the zinc coffins. Is this the result of editing by a female, antiwar writer, or does it mean Russian men are reluctant to tell war stories? I can’t believe it’s hard to get vets of any war to start trotting out the war stories, so I’m inclined to think that either the editor suppressed them or, perhaps, Afghan battles just didn’t make good stories.

That may well be it, because most of the casualties seem to have been inflicted by landmines. And mines just don’t make very good war stories: boom, you’re maimed.

Or maybe Russians just didn’t have time to perfect their war stories, because they were trying to deal with the chaos that soon followed the end of the Afghan campaign. Maybe that’s the biggest Nam/Afghan memoir difference: the Vietnam War struck a country at the peak of its power and wealth. In a real sense, America could afford to listen to the Nam vets’ accounts, even savoring the exotic gore they offered to a country swaddled in comfort. The Afghan vets’ stories were lost in the far greater catastrophe playing out in the homeland. The USSR they fought for ceased to exist a few years after their Afghan war ended. Maybe the best story in Zinky Boys is by an ex-artilleryman distracted from his own case by that of another victim of the collapse of “the Motherland”:

“There’s an old woman living in our block…As a result of all these articles nowadays, the revelations, exposes…she’s gone mad. She opens her ground-floor window and shouts, ‘Long live Stalin! Long live communism — the glorious future of all Mankind!'”

The grief of aging women — that’s the biggest impression you take from Zinky Boys. Why the prominence of mothers in this war book? My guess, and it’s no more than a foreigner’s wild guess, is that gender roles are so sharply, excitingly polarized here that only a woman could negotiate the shame of telling the misery of those who served in a Russian defeat, since her gender has far more license to explore grief and sorrow. Hence, perhaps, the soldiers’ mothers’ horror at not being able to embrace their sons’ bodies: a vital part of their role had been denied them, locked up in those closed zinc coffins.

John Dolan is co-host of the Radio War Nerd podcast. Subscribe here.

This review was first published in The eXile on September 4, 2004

We must remember the millions who died in the Soviet camps. Why? That nasty, nagging “why?” kept dogging me as I made my way through Anne Applebaum’s long (600 pp.) and well-researched history of the GULAG. If I hadn’t lived in Moscow from 2002 to 2004, I probably wouldn’t have had the nerve to challenge Applebaum’s mission, commemorating the victims of Stalinism. But one thing you learn in Russia, whether you want to or not, is that the Russians are not interested in this subject at all. And their lack of interest is strangely contagious, infecting even formerly avid fans of Zek literature like myself.

Before living in Russia, I used to wonder why none of the sons or grandsons of GULAG prisoners hunted down the thugs who tortured and killed their relatives. It happened in China, where descendants of those persecuted by the Red Guard tracked down and beat or even killed ex-Guards. And there’s an army of well-funded pursuers tracking down the few living ex-Nazis. Why didn’t Russians go after Stalin’s surviving executioners?

The simple, disturbing answer is that they’re not interested. And that bothers us. It’s not that the West cares very much about the Russians — either the millions who died, or the 140 million struggling to live in contemporary Russia. We’ve made our indifference to them pretty clear, over the past fifteen years.

Rather we need to believe that everyone shares our alleged dedication to the Christian-derived notion that we have to love everyone. And that means mourning, or at least going through the motions of mourning, every mass death.

So we wait for the Russians to start moaning and gnashing their teeth over the GULAG, as we would wait for a bereaved family to start keening over their loss. We’ve been standing nervously outside the Russians’ hut for over a decade now, waiting for those banshee wails to trigger our public tears.

And there’s been this silence — at first puzzling, then offensive. And at last, realizing that these shameless Russians aren’t going to start their own rites, we decided to do the job ourselves.

Thus Applebaum’s book was born. And it has the feeling of a belated, awkward funeral oration by one who didn’t know the deceased very well, but is driven by a deep sense of moral righteousness to perform the proper rites. To her credit, Applebaum knows and admits that the Russians themselves aren’t interested in commemorating the victims of the camps. She mentions that the only monument they have in Moscow is a single stone from the Solovetsky Islands. We lived a block from that stone, and for two years we walked past it nearly every day. I don’t recall seeing anyone take notice of it, even once. It sat there, splattered with birdshit, facing Lubyanka — completely forgotten. By contrast, the statue of Dzerzhinsky, though exiled to the Statue Garden by the river, is covered with curses and homage, just biding its time.

Anne Applebaum bears the sufferings of Stalin’s GULAG victims

In her final chapter, “Memory,” Applebaum attempts to account for the Russians’ indifference. She’s quite intelligent for a conservative, and surprisingly fair-minded for someone associated with a Tory rag like the Spectator. She even acknowledges that anti-Soviet rhetoric is soiled, in the minds of most contemporary Russians, by its association with the Gaidar kleptocracy, and offers a cogent summary of other possible factors:

“There are some good, or at least forgivable, explanations for this public silence. Most Russians… spend all of their time coping with the complete transformation of their economy and society. The Stalinist era was a long time ago, and a great deal has happened since it ended. Post-Communist Russia is not postwar Germany, where the memories of the worst atrocities were still fresh in people’s minds.”

The comparison to post-1945 Germany is the crucial one, the one by which contemporary Russia keeps disappointing and annoying righteous Westerners like Applebaum. This is yet another case of the “Hitler Standard,” by which the Nazis are the gold standard of evil, and the painful rehabilitation of Germany after 1945 the gold standard of recovery.

And of course this version of what happened in Germany in 1945 requires a suppression of memory at least as great as that involved in Russia’s apathy towards Stalin’s crimes. In the first place, it’s not the case that Germany’s crimes, in general, made much of an impression on “people’s minds.” Germany’s crimes against Russians, in particular, were little noticed nor long remembered in the West — despite the fact that the majority of the Wehrmacht’s victims were Slavs.

Most massacre victims are the sort of people not likely to be remembered. This is one of those almost-tautologies that’s still worth saying, like the old evolutionary biologists’ joke that most of us are descended from people who didn’t die before puberty.

And as another cynical French wit put it, we are all very good at bearing the sufferings of others.

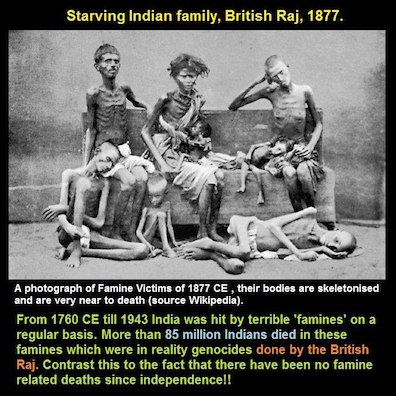

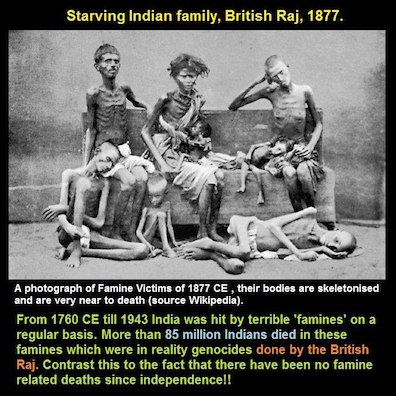

Only when a massacre is unusually dramatic and interesting, and/or involves people to whom we feel particularly close, do most of us feel anything. In other words, the Christian-derived premise that there is some Enlightenment moral sense in each of us, which reacts with instinctive horror at any mass suffering, is simply nonsense. There is no such sense — and a quick look at the archives of a Tory magazine like the Spectator, for which Applebaum proudly toiled, would reveal that fact a million times over. Ever hear of the “Black Hole of Calcutta”? Of course you did. That terrible overheated room in which some English prisoners were kept during the Indian Mutiny, so stifling that some of them actually died! Now, let’s do the math: what is the ratio of Indians killed during the British occupation to British prisoners stifled in the Black Hole? Few of you will have any idea, because those millions of dead never registered with us.

Applebaum would not have been capable of accepting a position with a vile publication like the Spectator unless her own consciousness contained at least one huge, highly adaptive amnesiac blob where all the crimes of the Empire should have been filed. So vast and horrific were these crimes, so long did they continue, that you could pretty much spin a globe, jab a finger at it blindfolded, and land on a spot where some Imperial force committed some sort of atrocity. (Unless, of course, you landed on ocean — though the Royal Navy would do its best to provide you with material even there.)

The crimes of history are optional. We mix, match and discard according to taste and convenience. It’s useful for Applebaum’s Tory backers to remember Stalin’s crimes because they can still use them to bash anyone who might want to beef up the National Health system with higher taxes. “Today an extra 1% VAT on my Jag convertible, tomorrow Kolyma!” is a very familiar war cry from these crusaders for human rights. Other massacres are dim stats, to be dredged up when necessary. Take, for example, all the tens of millions of dead in the Japanese occupation of China. They are rarely invoked in the West, because we don’t need them. The Japanese are thoroughly spent, neither a threat nor a bad example of anything we worry about at the moment. The Chinese are more of a worry, making the invocation of their dead a dangerous concession. And in the Tory mind, those dead are connected with ignominy: the surrender of Singapore without a fight, the sinking of the Repulse and Prince of Wales…and so it goes, with a huge number of tangential mental associations determining which of the billions of corpses clogging the earth will be dug up and flung at one’s opponents at any particular moment.

In this context, the Russians’ lack of interest in Stalin’s victims seems quite natural and healthy. It’s Applebaum’s arduous disinterment of them that ends up seeming forced, disingenuous and surprisingly dull.

John Dolan is co-host of the Radio War Nerd podcast. Subscribe here.

Don’t be a dick! Buy John Dolan’s comic memoir “Pleasant Hell” (Capricorn Press):

Buy John Dolan’s novel “Pleasant Hell” (Capricorn Press).

This article was published in The eXile on June 28, 2002 Dispatchesby Michael Herr , Vintage 1977 Everything We Haded. by Al Santoli , Random House 1981 Once A Warrior Kingby David Donovan , Ballantine 1986 Chickenhawk by Robert Mason , Penguin 1983 We Were Soldiers Once…And Young by Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore (ret.) and Joseph L. Galloway , Harper Perennial 1992 |

| |

Mel Gibson’s Vietnam movie We Were Soldiers just hit New Zealand, so I’ve had to deal with endless commercials of that sagging beagle-face of his, carefully smeared with artificial dirt and smoke, rallying the troops in a laughable attempt at a Southern accent. Having seen The Patriot, featuring Mel doing a similarly rotten Carolina accent as he ran around chopping up Redcoats with a teeny little tomahawk, I think I’ll skip his remake of Vietnam.

But it did send me back to reread the book Mel bought to use as the basis of the film: We Were Soldiers Once…and Young. It seemed like a good occasion to review some of the innumerable Vietnam memoirs I’ve bought over the years.

Yes, chillun, I am old enough to remember that once upon a time, nice people didn’t even want to talk about Vietnam, let alone read about it. Now how did it git so’s they don’t hardly wanna talk ’bout nuthin’ else? Gather ’round the fire and I’ll tell you all about it.

Avoiding Nam was pretty much a fulltime job for sensible Americans of the 70s. It didn’t look like fun yet — not when it was actually happening. That took several years and about a thousand war memoirs. At the time, it looked like a remarkably uninteresting war, with wretched losers from inland America standing around the paddies twitching nervously, wondering whether the water buffalo in the next field was going to whip out a Kalashnikov and start shooting.

That changed very slowly. The first book to make Nam seem cool was Michael Herr’s Dispatches. This was the first Nam book taught at universities (I encountered it in a course at Berkeley). Herr wrote as one of the college boys who didn’t fight. He was there to watch, write, and make a name for himself. He wrote guilty erotica, and spoke for the smart guys who got themselves deferments but always wondered what they would’ve done if they’d gone: “You know how it is, you want to look and you don’t want to look. I can remember the strange feelings I had as a kid looking at the war photographs in Life…”

Since the deferred guys were the core of the teaching pool at most American universities, they tended to assign Herr’s book, and it became one of those “instant classics” which make it more for demographic than artistic insights. Herr’s book was a first draft of Apocalypse Now, with Hendrix soundtrack and quick cuts between cool gore and Saigon lies. It doesn’t read particularly well now; there’s too much caution there, like someone trying to do Hunter S. Thompson after halfheartedly inhaling one tiny line of speed. But then that’s always the way to crack the upscale porn market: just a little whiff of the really hard stuff, enough to grab the safe people. After all, the safe, guilty males of the Nam era had two advantages over the ones who went: they had graduated to teaching jobs and could force large numbers of students to buy the book — and they were alive.

Herr’s book came out in ’77, two years after the fall of Saigon. It was a while before anybody wanted to hear from the losers who’d actually gone and fought in Nam. It took a lot of concerted lying, in films like Deer Hunter, to erase all those images and persuade the home folks that the enterprise had been a noble one.

In strictly literary terms, this great lie was of some benefit, because there are few genres as rich as the war memoir. Virtually anyone who saw combat and has a decent memory can write a decent book about it — and Vietnam, a war characterized by thousands of small skirmishes, was richer in incident and gore than an inner-city basketball tournament. When next you hear that rough voice asking, “War — what is it good for?”, you tell it: “First-person memoirs, that’s what!”

By 1981, the memoirs were coming fast. The first and in some ways still the best was Everything We Had, a collection of oral reminiscences by 33 vets who’d done everything from nursing the wounded to slitting throats with Bob Kerrey and his pals. I’d still recommend this book as a starter-kit for the prospective Nam fan, because the 33 voices offer something for virtually everyone. Parts of the book are very funny, as when Gayle, the cute li’l nurse, recalls her answer when asked if she’d serve on a ward for Vietnamese casualties: “And I said, ‘No, I would probably kill them.’ and she said, ‘Well, maybe we won’t transfer you there.'” And they say the Army has no heart!

By the early 80s, it was not just cool to’ve served in Nam; it was glorious. It was, in fact, the only sort of martial glory available (Grenada didn’t quite carry the same “cachet,” as they said in the Reagan era.) Every Vet still alive and compos mentis — and some who weren’t — headed for that early-model KayPro or Northstar keyboard to turn his ranting into cash. They were a little confused at first, having been shunned and pitied as they dragged their way from halfway house to detox to medium-security institution…but slowly a canny ambition shouted down the voices babbling in their addled heads with the news that the war stories which had driven the wife and kids to move out with no forwarding address were now box-office boffo.

And damned if many of them, fingers trembling on the keyboard, one hand on the Jack Daniels or rolled-up twenty, didn’t hunt-and-peck out some quite good books.

This high literary output was a delayed gift of the utter lack of strategy which doomed the American enterprise in Vietnam: a war which consisted largely of sending small contingents of infantry out into the jungle to find the enemy, usually by getting ambushed, is bound to be a military disaster — but equally bound to produce an extraordinary number of fantastic combat tales. As Walter puts it in Big Lebowski: “Me and Charlie, eyeball to eyeball.” Throw in the treachery of the South Vietnamese, the social and racial bombs going off non-stop back home, the feeling of abandonment, the music — greatest soundtrack of any war ever — and you had the elements of better stories than more intelligently-conducted wars could ever yield. (If there were any true aesthetes worthy of Oscar Wilde’s mantle, they’d’ve agitated for the continuation of the war at all costs. Alas, dreary Utilitarian ethics have conquered us so thoroughly that not a single voice urged the continuation of the war as the greatest performance art of the century.)

I’ve read a dozen of these memoirs, and enjoyed almost all of them. They come in all flavors. There’s the raunchy defeatism of F. N. G., which describes a “fuckin’ new guy” entering an infantry squad after Tet, when the Americans had pretty much given up trying to win and were fighting a strange, highly mobile but essentially defensive war. Then there’s Once A Warrior King, describing one very conservative Virginian’s relatively straightforward war, working with a fiercely anti-VC village in the Delta. This is Greene’s Quiet American told by the quiet A. himself, as it were — and he tells a good story. It’s the food I remember best, in that one: the long descriptions of roasted rat with fish-sauce. That’s one of the delights of war and prison memoirs: you can count, in these solidly grounded stories, on some excellent descriptions of meals good and bad. (The POW memoir, combining the genres, often yields the most mouth-watering descriptions of all; if you want a book full of the delight of eating, read Brendan Behan’s one good book, Borstal Boy.)

The best of all these might be Chickenhawk, the story of a helicopter pilot who was, as Martin Sheen says of “Chef” in Apocalypse Now, “…wound up a little too tight for Vietnam.” Robert Mason, the pilot-narrator, takes the reader in and out of so many LZs, hot, cold and medium, that you develop a veteran’s wince everytime his slick starts descending toward the purple smoke.

One of the many delights of Mason’s book is that it describes the battles for the Ia Drang — the same campaign glamorized in We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, the book Gibson filmed. The campaign, which is depicted as a noble, though doomed, strike for freedom in We Were Soldiers…. doesn’t come off so well in Mason’s memoir. In fact, he and his fellow pilots seem to have done something the generals in charge of the operation didn’t do: read the books about earlier French campaigns against the Viet Minh in that same valley. Mason and his drunken buddies end up predicting the failure of the campaign while their superiors are still sending home the sort of communiques which did so much to cement the American Army’s reputation for…er, “emphasizing the positive,” let’s say.

But Mason’s topper, his most brilliant passage, comes at the very end, in the epilogue summarizing his messed-up return to civilian life. Here’s the superb two-paragraph conclusion, describing his next move after the early drafts of his Nam memoir had been rejected and he’d failed in everything he tried since getting back to The World:

“What did the desperate man do? I can tell you that I was arrested in January, 1981, charged with smuggling marijuana into the country. In August 1981, I was found guilty of possession and sentence to five years at a minimum-security prison. I am currently free as of February 1983, appealing the conviction.

“No one is more shocked than I.”

Just roll that last sentence over on your tongue. “No one is more shocked than I.” Now there is a meal. Even the fussily correct grammar, that annoying “…than I” rather than the colloquial “than me” or “…than I am”; so perfectly droll, such a change from the Nam dialogue in which every other word is “fuckin'”. And the grand historical irony, that the junked helicopter jock should become desperate enough to sell his one skill to the only people who wanted it, the drug dealers, designated New Enemy of the Reaganites. And the timing! Mason’s manuscript got four rejections in the years leading up to 1981, when the memoirs started appearing. A little later, and he’d’ve been cool. But that would have been disastrous. To go to prison for piloting a helicopter full of drugs, albeit unworthy boring drugs like marijuana, even as that great war-dodging hypocrite Reagan shoved his leathery grin in front of the flag — ah, It’s a fate better than death.

This article was published in The eXile on June 28, 2002

The recent death of Andrea Dworkin didn’t even make the small print news in Russia. Feminism, at least the feminism of the kind Westerners take for granted, never caught on. Patronizing Westerners often see that as a sign that Russians are culturally too primitive. Russians, particularly Russian women — and particularly the Russian female intelligentsia — literally laugh and roll their eyes when you mention feminism of the American or West European brand. The reason is fairly simple: Russians haven’t quite learned the Western art of sloganeering for radical philosophy without meaning a word of what they say. A Russian woman would assume that if you’re a feminist, you’d actually have to live out the philosophy. In that sense, Andrea Dworkin was, in her own way, the only “Russian” feminist in America — and that is why she was so hated.

(more…)

Posted: September 14th, 2013

Auden is the worst famous poet of the 20th century. He simply cannot write a decent line, let alone a decent poem. Some of his very worst poems are among those “classics” found in every anthology of Modern poetry. They’ll continue to clog those penitential first-year university texts until we find the courage to laugh out loud at stanzas like this:

Earth, receive an honoured guest:

William Yeats is laid to rest.

Let the Irish vessel lie

Emptied of its poetry. (more…)

Posted: August 28th, 2012