|

Birthday Boy

A Week in the Life of the Kremlin Chief of Staff

A Stringer/eXile Exclusive

(taibbi@exile.ru)

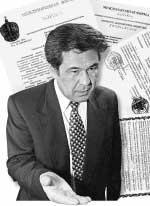

By most accounts, he’s at least the second-most powerful man in Russia, after President Vladimir Putin.

According to a significant minority, his status is even greater. There are many observers who believe that Kremlin Chief of Staff Alexander Voloshin is not merely the man whispering in the king’s ear, but the gatekeeper to the throne, whose good graces Putin himself once had to court in order to pass. Although the full story has never been told satisfactorily, most versions of the maneuverings within the Kremlin during the summer of 1999—which landed Putin in the post of Prime Minister—have Voloshin occupying a central role, brokering Putin’s ascension.

Then as now, the balding, bearded, shifty-eyed Voloshin was the Kremlin Chief of Staff, only then he was serving under ailing president Boris Yeltsin. He was considered a central figure in the Yeltsin “Family,” the privileged group of court insiders who surrounded Yeltsin in the waning days of his rule. He was known to enjoy a close relationship with Yeltsin’s daughter, Tatyana Dyachenko, and was long thought to be a henchman for another key “Family” member, the notorious businessman and oligarch Boris Berezovsky.

Years before, Voloshin’s name was linked to Berezovsky’s in the scandal surrounding the AVVA, a kind of Russian national car, modeled after the Volkswagen, that Berezovsky had proposed building. Together with Voloshin, who worked on the project, Berezovsky raised an enormous amount of capital to finance the construction of the AVVA. But as so often happens in Russia, the car was never built, the money disappeared, and everyone involved got promoted—Berezovsky assumed control over a large part of Russian industry, and Voloshin began to advance quietly in government, eventually becoming Yeltsin’s right-hand man.

Because of this link, it was frequently speculated that the decision to put forward the unknown KGB veteran Vladimir Putin as a candidate for Prime Minister that summer was conceived by Berezovsky, with the faithful Voloshin merely executing the plan.

Two years later, however, Berezovsky is out, his commercial empire is in ruins, and he is facing a series of criminal investigations. Voloshin, meanwhile, has remained in place as Putin’s Chief of Staff. To the surprise of many, Voloshin also survived Putin’s first major cabinet reshuffling last month. There was speculation that Putin would dispense with all of the major holdovers from the Yeltsin era once he’d completed his first year in office. Staying power through successive periods of purges is rare in Russian national politics; Voloshin’s ability to remain entrenched in the Kremlin over the course of the last few years suggests that there is some compelling reason why he has not suffered from his associations with either the mafia overlord Berezovsky, or the deposed monarch Yeltsin.

Which brings us to the present. A few weeks ago, the eXile, along with its Russian partner Stringer, unexpectedly came into possession of a compact disc containing some six hours of telephone conversations. The package in which the disc was delivered contained a note indicating that the recordings had been made on Voloshin’s Kremlin telephone line—not the phone on Voloshin’s desk, but the one in the reception area of his office. Through a careful review of the disc, we were able to determine that the recordings covered a six-day period—from Wednesday, February 28 through Monday, March 5 of this year.

Your guess is as good as ours as to the source of the recording. In fact, we’d prefer to leave it to Stringer to explain that end of the story when they publish their lengthier feature about the recordings next week. Suffice to say that we’ve determined that the recordings are genuine, and that we will make an effort to allow doubters to decide for themselves. Audio excerpts of the recordings will be posted on the eXile website following the release of the Stringer feature next week.

The period covered by the recordings was an extremely interesting one for several reasons. For one thing, it came during Voloshin’s birthday—the Chief of Staff turned 45 on day four of the six-day period (Saturday, March 3). The disc therefore contains calls from scores of Russian political heavyweights, with one tripping over the next to offer gifts and effusive expressions of congratulation. The nature of these conversations, and the way in which they were received by Voloshin and his subordinates, go a long way to determining the status of these politicians in the eyes of the Kremlin.

The second, more pressing subplot of the recordings involves the no-confidence vote that was about to be put forward in the Parliament. To backtrack a little, the Duma, on the initiative of the pro-Putin Unity party, had put forward the idea of passing a vote of no confidence in the government of Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov. The measure, which ultimately failed, has been variously interpreted as a ploy by the Kremlin to create an excuse to dissolve the Parliament (which would have allowed for new elections that would presumably have resulted in a greater pro-Kremlin majority) and as a means of restoring the credibility of the captive opposition, the Communist party, by allowing them a loud but ultimately unsuccessful public rebellion. In either case Voloshin, as a key Kremlin insider, was assumed to play a significant role in the hatching of the plot.

The recordings seem to bear out that assumption. And, because they cover such a lengthy period of time, they also provide a rare look at how day-to-day affairs are managed at the seat of power in Russia: the protocol observed by politicians looking to gain an audience, the language they use on the phone, the strategies they employ in repeat calls to press some issue with the chief. The also provide an off-camera look at Voloshin himself, as he appears in the calls he takes personally.

Unfortunately, the material on the recordings is too vast to cover in the space of one article. A more complete version of the transcript story, including in-depth commentary, will come out in the May issue of Stringer, which will hit the newsstands in about a week and a half. In the meantime, we will have to limit ourselves to a broad review of a week in the life of the Kremlin chief, beginning with the day one.

Wednesday, February 28, Call #6

Journalist Alexander Minkin

|

Minkin is the first big name to call. It’s worth noting that the bearded journalist, lately back with Moskovsky Komsomolets, was a Duma candidate in 1999 on the Fatherland All-Russia ticket—opposing, in other words, the Voloshin-supported Unity Party. Both Fatherland and Minkin fell on hard times after Unity dominated the 1999 Duma elections, but Minkin, it seems, has found a way to put himself back in the Kremlin’s good graces. At the very least, Voloshin’s secretary does not hang up the phone when he calls:

- Reception, hello.

- Hello, this is Minkin Alexander.

- Good day.

- Tell me, is Alexander Staliye-vich in? I can’t seem to get hold of him.

- Not yet. I’ll look now, wait, please… he was asking just yesterday… No. You just want to talk to him?

- Yes. Actually, it’d be better if he set up a meeting.

- Understood. I’ll just write that you called to set up a meeting.

- Yes.

- If there is any kind of reaction, I’ll call you straight away.

- Thank you.

|

The timing of Minkin’s call was interesting. Just two days later, Moskovsky Komsomolets ran a lengthy article by Minkin which blasted the man who many consider to be Voloshin’s closest political ally, Kremlin ideologue Gleb Pavlovsky. The thrust of Minkin’s article was that Putin’s chief ideological adviser was a cheat and a liar and should be removed by a regime that has enough “common sense” to know better. Minkin’s article was aimed at least in part at a general audience, making such populist observations as the following:

As far as Pavlovsky is concerned, those who can’t understand him, should read Yelena Bonner’s words: “I knew Pavlovsky for what he was back in 1980 or 1981, when he gave evidence against Sergei Adamovich Kovalev’s son to the KGB. He showed who he is.”

But Minkin was not only playing on popular anti-KGB sentiment; he was also clearly making a rhetorical pitch to Russia’s chief KGB icon of late, Vladimir Putin, who would not be likely to look down upon Pavlovsky for having given evidence to the KGB. In the piece, Minkin argues at length that Pavlovsky has outlived his usefulness to the regime, that Putin, safely in power, has no need for an intriguer and creator of false enemies and media distractions. Toward the end of the article Minkin makes a classic appeal from the ordinary Russian to the better judgment of the Tsar:

The president should use clever, experienced, and respected people with good reputations. The president has enough common sense.

If Voloshin were indeed a close ally of Pavlovsky, it would be hard to imagine him having a friendly chat with a reporter who was just days away from running a demolition job on his friend. The tone of Minkin’s article suggests an appeal aimed over Pavlovsky’s head; perhaps criticism of Pavlovsky was not unwelcome to Voloshin, whose name was conspicuously absent from the Minkin piece. It’s impossible to draw any conclusions, but the timing, again, is interesting.

Call #15

ITAR-TASS

|

- Reception. Hello.

- Good day. Forgive me, for God’s sake. I’m calling from ITAR-TASS. Maybe

you can help us.

- Yes.

- Do you have a number for Pavlovsky?

- Yes, of course.

- His birthday—to congratulate him.

- Is it today?

- March 5th.

- Uh huh. We’ve all got March birthdays, it seems. I’ll give

it. [Gives phone number].

- Thank you.

- Reception. Hello.

- Good day.

- Hello.

- Semenishyev Vasily Nikolayevich. I’m calling on the following question. I

need the telephone number for Anatoly Borisovich Chubais.

- Semenishyev, excuse me, you’re from where?

- Vasily Nikolayevich.

- Yes, Vasily Nikolayevich.

- I’m the director of the Russian cooperative group of [unintelligible] ventures.

- Why are you calling us? Call information [gives number for information].

- Uh… thanks.

- Thanks.

Of course, it was completely natural for this Semenishyev to call Voloshin’s office looking for Chubais’s number—after all, it used to be Chubais’s office! (Chubais was Yeltsin’s Chief of Staff in 1996). But it appears that Chubais, who has been struggling to maintain his seat as the director of the national power company RAO UES, is no longer on Voloshin’s short list of friends. On the other hand, the idea that Voloshin’s office would be a good place to look for a number for Pavlovsky—the dissident-turned-media-mastermind who once claimed to have “created” the Putin phenomenon—elicited no surprise whatsoever. Pavlovsky’s name would figure heavily in Voloshin’s phone traffic in the upcoming week.

Call #28

The Foreign Affairs Ministry

Just one day before, on February 27, the Russian oil company Zarubezhneft, in conjunction with Tatneft, was given permission by the UN Iraqi Sanctions Committee to drill 45 oil wells in northern Iraq. Just over a week before that, on February 16, U.S. and British warplanes attacked Iraq, prompting, on February 21, a call from Iraq for Russia to remember its “responsibility” to hold U.S. power in check. In light of these events the following call, from the Russian foreign ministry, offers some interest:- Hello. The RF Ministry of Foreign Affairs has the honor of troubling you with a call.

- Yes, I’m listening.

- We have the following question… [inaudible] to consult. Just now the Iraqi embassy has contacted us and asked for a list of government officials, including the members of the presidium. Who in the President’s administration is handling this and where can we get such a list, can you advise us?

- Try Abramov. He’s at [gives number]. That’s the reception number I’ve given you.

- Thank you.

- You’re welcome.

Alexander Staliyevich never made it into his office that afternoon; he was tied up in meetings all day and didn’t take any calls. Later in the day his secretary would call up a friend and conspire to appropriate for herself a pair of theater tickets, to a show called “Kopellio” that the Kremlin palace had offered to Voloshin. “They offer them to him because they think he’s such a theater buff,” Elena says. “But in fact he doesn’t go anywhere…. They say, ‘give it to him’, but they don’t necessarily mean exactly to him.” The two women discuss the ins and outs of the operation for a while. Elena finally explains to her friend at one point what the plot of “Kopellio” is, leading the conversation in a decidedly Gogolian direction.

The plot is apparently the following: a boy falls in love with a doll… in short, a comedy.

But I know “Kopellio.” In general, to be honest, it’s not altogether a comedy.

Well, that’s what I heard, that’s what I was told.

The rest of the day is mainly a series of cold calls. A man claiming to be an old acquaintance of Voloshin’s calls up and says that he is “between jobs” and would like to discuss “service to the Motherland.” The day ends with a male evening watchman taking over for Elena and answering a few calls, both hangups.

Thursday, March 1 Call #2

“I’m not an ordinary citizen. I’m an investor.”

The second call to Voloshin’s office on this day comes from a belligerent official from the Orthodox Church, a Father Georgi Dolgoruky. In his threatening tirade, the priest reveals a thing or two about the relationship of the Kremlin to various nongovernmental political figures. Father Dolgoruky is upset that Voloshin has been ignoring him, and gives him a piece of his mind:- I can’t seem to get these papers to Alexander Staliyevich.

- What’s the problem?

- Well, I deliver them to the usual place. They tell me: “In a month.” What “month,” if they need an immediate decision? With me it’s always been: I give the papers, and on the next day I get an answer. I’m not an ordinary citizen of the Russian Federation, you understand. I’m an investor. If I come, I come for a few days, then leave. I can’t wait for a month.

- Well, you understand, we have a procedure here by which papers are delivered. We can’t take papers from everybody here in this office.

- I’m not everybody! I can go to Putin faster than to you.

- Well, be my guest.

- Therefore you are told: if I say, I know. What I’m saying.

- And I know what I’m saying.

- Tell Alexander Staliyevich that I called.

Dolgoruky calls back several times over the course of the next few days, but never reveals just what his “investment” is.

|

Call #8

Kinder Surprise

Early in the day there is a mildly suspicious call from the office of Sergei Kiriyenko. The caller asks Voloshin’s secretary for the phone numbers of some of “the prikreplyonnykh” (reinforced, protected), whoever they are:- I’m calling from the office of Kiriyenko. Tell me, please, can I look from someone among the prikreplyonnykh [unintelligible]? How can I find them?

- They’re not in yet.

- Can I have one of their mobile phones?

- You know, I don’t even know who’s going to be in today.

Call # 15

Gleb Pavlovsky

|

- Voloshin’s office.

- Good day. Pavlovsky.

- Good day. Yes.

- Is two o’clock still on?

- You know, probably not, because Alexander Staliyevich just

came in and a one hour meeting will be just starting now. Why don’t you…

in the best case, come at 2:30.

- Okay. Good. Thank you.

It never comes out what that meeting was about, but it’s worth noting again that this comes just two weeks before the no-confidence vote. Further information supporting the idea that the two men discussed this issue comes later on.

Call #26

Gazprom

|

- Hello. This is Gazprom. Vyakhirev’s office calling. Tell me, please, could Rem Ivanovich speak with Alexander Staliyevich after six?

- Well, we’ll be here. Let’s try.

- We’ll try. Because we have a big meeting going on right now.

- Yes, us too. He’s not here right now. At a meeting.

- But by six he should be around?

- After six he’ll be here, yes.

- Thank you. Goodbye.

Friday, March 2

Call #5

Birthday greetings

It is the day before Voloshin’s birthday and the congratulations begin pouring in right from the start. The first call comes from an automaton in the office of the president of the Far Eastern Federal okrug, asking where to send gifts. He is followed, ironically, by an automaton in the Federal Fisheries Committee—the place where onetime Far East heavyweight Yevgeny Nazdratenko moved after being banished from his post as Primorye governor. First the new Far East power calls, then the old-school version calls.In the fifth call, however, a real heavyweight calls up, personally:

- Reception. Hello.

- Lena? Has he showed up yet?

- No, not yet, Tatiana Borisovna, but now… if you want, wait a moment.

- No, allo. Has Lyuda come in?

- Lyuda’s here.

- Oh, well then, that’s all.

Call #30

Dobrodeyev to Voloshin: “The problems that were there are removed.”

|

The best gift offer of the lot comes from Kemerovo governor Aman Tuleyev’s office.

|

After a lengthy series of these calls, Voloshin himself unexpectedly comes on the line to take a call from RTR director Oleg Dobrodeyev, who is calling from Sochi. eXile readers may recall that the director of the local director of the VGTRK (All-Russian Television and Radio Committee) was removed in February, on the order of Mikhail Lesin, on the eve of a mayoral election in which a Communist candidate was threatening to defeat a pro-Kremlin incumbent. In this regard the following conversation is an extraordinary one. Note Dobrodeyev’s abject groveling before Voloshin—he apologizes no fewer than four times in the course of a very short conversation:

- Hello.

- Alexander Staliyevich?

- Yes, Oleg.

- Hello, it’s Oleg. Alexander Staliyevich, I replaced the chief in Sochi, but there’s a real cyclone here, and I’m stuck in the airport for three hours.

- I understand, I understand.

- I beg your forgiveness. But this is an emergency. It’s not my fault.

- [irritated] Yes, I understand. But don’t worry, it’s nothing, no disaster.

- You forgive me?

- Yes, of course. Is everything relatively calm in Sochi?

- Yes, yes, yes. In fact I was in Krasnodar yesterday, today in Sochi, later [unintelligible], took care of everything, everything is good.

- Oo-hoo. Well, excellent.

- Therefore the problems that were there have been removed. Zyuganov called me today.

- Yes.

- He said he was going to take all possible measures.

- How interesting.

- I don’t know.

- Well, let him take them. We… also will.

- I don’t know, what’s what…. They are preparing some other announcement to go on two stations. Well, you saw them yesterday and the day before.

- Saw part of them. Well, it’s okay.

- Well, it’s simply that they seem to be in a state of extreme… over-agitation.

- Well, that’s fine. That’s good.

- That’s… that’s what I wanted to say.

- Uh huh. Okay. Thank you.

- Alexander Staliyevich, forgive me.

- Yes, fine, thank you.

…the initiative of the communists (on a no-confidence vote to the government) is a political mistake first of all because the strongest player today is the President, and no matter what the outcome, he is risking nothing. For some unknown reason, the Communists think that the president will, under no circumstances, take such a step as dissolving the Duma.

Now, this may have been an act on Pavlovsky’s part, or he may have been giving a sincere assessment of the political situation. But from Dobrodeev’s call it does appear here that Zyuganov and the communists were legitimately “agitated,” and one might assume that the “measures” Dobrodeev called for might have included continuing the no-confidence campaign.

Voloshin here says, “Well, that’s fine, that’s good” and “We also will” when Dobrodeev informs him that the Communists are planning to take measures. Three days after this call, on Monday, March 5, the Unity party announced that it was considering supporting the no-confidence measure. On that same day, Voloshin gave an off-the-record phone interview—captured on these recordings and published later—in which he intimated that the whole no-confidence vote had been dreamed up by him and Pavlovsky with the aim of dissolving the Duma. These calls, taken in context, suggest that the chronology of the no-confidence story might be that it was a movement that began at least in part in earnest, only to be subverted and appropriated through an opportunistic ploy by Pavlovsky and Voloshin.

Call #64

Tatiana Dyachenko—at work and at play

|

Respected Alexander Staliyevich! I’m glad that in a difficult times I had the opportunity to work with you. More than once I’ve been convinced of your extremely high level of professionalism, your preparation, your competence, and your excellent business and personal qualities. I value the sincere and trusting relationship which has formed between us. From all my soul I wish you and those close to you, respected Alexander Staliyevich, strong health, success, and all my best.

But Dyachenko’s more interesting, and serious call comes about an hour later, in call #78. In it, she speaks directly to Voloshin, and discusses the “privatization” of Yeltsin’s presidential dacha in Barvikha, a neat piece of state embezzlement which is apparently being handled by Voloshin, former Federal Property Fund chief Igor Shuvalov, and director of Presidental Affairs Vladimir Kozhin. Note the way Dyachenko first makes sure to congratulate Voloshin on his birthday once again before getting down to business:

- Hello.

- Hello, Sasha?

- Hello. Yes, Tan, hi.

- Sasha, I wanted to know, when can I come to congratulate you?

- I don’t really know. Let’s get in touch on the phone later. In general I was going to try to take tomorrow off.

- Yes?

- Uh huh.

- Well, okay, let’s call each other later…. [pauses] Sash, I also talked with Igor Ivanonivch Shuvalov. He’s got almost everything all ready, he’ll take care of it at the beginning of next week. The only thing he needs is a paper from Kozhin.

- Which one?

- Well, a request as it were for the transfer of the object.

- Oo-hoo.

- Well, and there [unintelligible] they’ll put it into action. And he said that [unintelligible] knows about it.

- That a letter is needed? About the letter he didn’t say anything.

- Sash, if it’s not too much trouble, maybe you could speak with him one more time?

- Sure. Okay.

Call #85

“Kiselyov gives me heartburn.”

More birthday congratulations follow Dyachenko’s calls: from Sberbank, from the Ukrainian embassy, from a Duma Deputy named Konstantin Vetrov, and others. In between those, Voloshin’s secretary finds time to chat with a friend and make a sarcastic crack about Putin: “He [Voloshin] was planning on asking our Great Leader for the day off tonight.” Later on in the day, however, an unnamed man, obviously a ranking Kremlin economic advisor, calls up, apparently in a call from London. After a witty exchange of birthday greetings (“it’s not easy to reach that age, no mean feat,” says the caller, “and particularly in this wonderful country of ours, with such diseases as anthrax and mad cow”), he speaks with the boss about the possibility of appearing on NTV that weekend:- I have one other question. I wanted to consult with you…. Now, the respected company NTV has expressed the desire to invite me on to the program “Itogi”, which will air on Sunday, to talk about the economy and the economic situation.

- Uh huh.

- In a live broadcast with Mr. Kiselyov.

- Aha.

- There. What do you say to that?

- And what’s it all about?

- Well they’re, how do you say, “Live from the banks of the Thames.”

- Oo-hoo.

- But I’m on an official trip, and I’m actually having a lot of meetings here….

- Oo-hoo.

- …with local officials.

- Oo-hoo, oo-hoo. And what’s the theme?

- Their theme is “The year 2000 in review. Economic Summary of the year 2000. The current economic situation.”

- Oo-hoo!

- They… judging from the questions they sent me, they, it would seem, would like, first, to make the observation—insofar as they can, obviously—that in the year 2000 the results were the best for the last third of a century, but that on the other hand, they want—judging by the questions—to call attention to the fact that the rate of economic growth has slowed.

- Oo-hoo… I don’t know. Kislyeov, of course… somehow he gives me heartburn.

- He gives me heartburn too, but on the other hand…. No, and in general, how do you say it, the Itogi show itself, how it’s all done, with some kind of subtext….

- Yes, yes, yes, they….

- That’s all absolutely clear. On the other hand… on the other hand, if you try to do it firmly enough and accurately enough….

- Oo-hoo.

- In fact it’s always better to take it from the receiving end, if you do it accurately, and how do you say, delicately, then it, in general, might also not be bad.

- Oo-hoo. And when already? This Sunday?

- This coming Sunday.

- Well, my assessment is, that it’s not worth it.

- Not worth it, huh?

- No. We have a difficult situation, the no-confidence vote…. They’ll somehow stick in their own context, the hell knows which one, yes? I think they’ll put in some kind of trap for you…. set you up somehow.

Saturday, March 3

Voloshin is absent Saturday morning, but the calls keep pouring in nonetheless. Gifts continue to come in: an assistant to Kiriyenko calls to ask for a pass to drop off a gift, as does Dobrodeyev, the Belarussian embassy, and others. Dyachenko calls to ask which mobile phone Voloshin can be reached at; she gets the number, and is in addition told by the Saturday secretary, Irina, that there are “papers” in Voloshin’s office that are awaiting Tatyana Borisovna. Irina may be referring to the text of Boris Yeltsin’s birthday greeting, which has yet to be read to Voloshin himself. A representative of Gazprom also calls, and is upset to find that Vyakhirev’s meeting has been canceled.

Sunday, March 4

Call #4

Hung over?

A groggy-sounding Voloshin contacts Lena.- Len. Talk to me.

- Uh huh. Thank you.

- Hello?

- Alexander Staliyevich, happy birthday to you.

- Thank you.

- Are you coming in to work today?

- Generally speaking… I’d rather not.

Monday, March 5

Call #52

“Fuck the Duma.”

Most of the day is occupied with late coming birthday well-wishers—the office

of the president of Tatarstan, Vladimir Potanin’s office, a series of others.

Not until call #52, from Svetlana Babayeva of Izvestia, does Voloshin himself

come to the phone. The interview he gives, apparently off the record, goes

into great detail about the no-confidence vote. In it, Voloshin, who calls

Babayeva “Svet” and sends a number of chatty and even flirtatious comments

her way, offers what seems to be a subtle mix of political posturing and candor.

By this time, Interfax had already reported that the Unity party was considering

supporting the vote, which would explain Babayeva’s comment about “livening

up the landscape.” It should be noted here that Voloshin at one point uses

the word trakhnut with regard to the Duma, which using its innocent

meaning in this sense translates as to “give a jolt,” but also, of course,

means “to fuck,”- I want to understand what’s happening. What, were you bored on Saturday? And you decided to celebrate your birthday by livening up the landscape? What is this?

- What is what?

- What’s going on with the vote?

- [unintelligible]

- I don’t understand anything. You want to dissolve the Duma or replace Kasyanov?

- Why replace Kasyanov? Kasyanov is an excellent person.

- That’s what I say: an excellent person.

- We should all hope for such Prime Ministers.

- Well… what then?

- Fuck the Duma, of course.

- Why?

- Something has to be [laughs] No. Realistically, the Duma can be better. It’s a normal parliamentary procedure. In Western countries if one of the political forces is absent, it can improve itself by virtue of extraordinary elections, it goes down that path boldly, and nobody thinks anything of it.

- You’re kidding!

- Seriously.

- But for some reason that doesn’t seem so realistic, considering that would be July, and through the elections not altogether the right people would be voted in….

- Ah. We’ve thought through that possibility. Somehow an improvement doesn’t seem to be in the cards.

- Everything will be fine, fine. It will be good.

- Are you serious?

- Yes.

- Will it be good, or will it be amusing?

- It will be amusing first, then good.

- Alexander Staliyevich… so you’re not touching Kasyanov?

- No, of course not.

- Because we have two versions, either the Duma or Kasyanov.

- Oh, come now. I can tell you honestly: it’s excluded.

- Well, I hope so.

- Yes.

- That the government will not be touched for now.

- He’s the only normal human being in the government.

- I’ll remember that.

- [laughs]

- I’ll remember that. So what, it’s the Duma, then?

- Yes, of course.

- Or what, you decided to liven things up, you were bored?

- No.

- You and Gleb Olegovich were bored? One has a birthday, the other has a birthday….

- Yes.

- So you sat down together and decided to liven things up?

- Yes, yes, yes, yes. That way, say. Decided to liven things up.

- As usual, you’re making fun of me….

- No, no, everything’s fine. We’ll fuck the Duma. Either now, or in the fall.

- What about the Duma bothers you?

- What bothers me? Well, there are a lot of Communists. The OVR is there, you understand….

- But they’re all bunny rabbits.

- Let them be bunny rabbits somewhere else.

- Understood.

- Now there’ll be kitty cats!

- So that’s how it is. It’s clear.

- Yes, yes. On the Unity list we’ll put a bunch of young girls, so that it’ll be fun in the Duma.

- My God!

- Yes, yes!

- [laughs] Alexander Staliyevich, it’s a good thing I haven’t completely lost my wits as a journalist. Otherwise I might print this.

- [laughs]

- Not everybody understands that kind of humor!

- You’re right!

As is well known by now, the no-confidence vote was a failure; Unity backed out of it, and the whole bid collapsed. Was the whole incident designed to send a message to the Communists to stay in line—or else? And will the Duma really be dissolved in the fall? As they say—only time will tell.

Voloshin in these transcripts comes across as a chatty, cynical wit, with a talent for keeping his social and political connections warm. The conversations with Dobrodeyev and Dyachenko and the others suggest that he is a real decision-maker inside the Kremlin, on matters ranging from the privatization of dachas to the removal of pesky provincial television station managers. Significantly, he does not mention Putin even once in the dozen or so personal conversations of his captured on the tape. Figures such as Potanin and Vyakhirev try to get through to him and are rebuffed for days on end. His attitude also suggests a significant shift in the equilibrium of power towards his position. Five years ago, it would have been impossible to imagine Chief of Staff Anatoly Chubais sarcastically describing Viktor Chernomyrdin as “the only normal human being in government” to a reporter and flightily discussing the possibility of teaming up with a Gleb Pavlovsky to dismiss him. Obviously, the Chief of Staff is a much more important person now than he was five years ago, while the Prime Minister is correspondingly, it seems, a less important person.

It is also clear from the transcripts that certain people who used to be Kremlin fixtures are now no longer in the inner circle. Except for Kiriyenko, who of course occupies an important place in the Putin government, none of the famed “young reformers” made regular calls to Voloshin’s office. Neither Chubais nor anyone from his office called even once, not even to send a trite birthday greeting. Kokh is mentioned once, in a Gazprom call, but then Kokh has crossed the river to Putin’s camp. On the other hand, Pavlovsky and Tanya Dyachenko appear to be regular confidantes, as does Lesin, who is greeted with familiarity by Voloshin’s secretary on two occasions.

The eXile will continue to publish excerpts from the Voloshin telephone transcripts in the upcoming months. For a more in-depth look at the recordings, be sure to look for the next issue of Stringer.