Posted: December 20th, 2013

Posted: December 19th, 2013

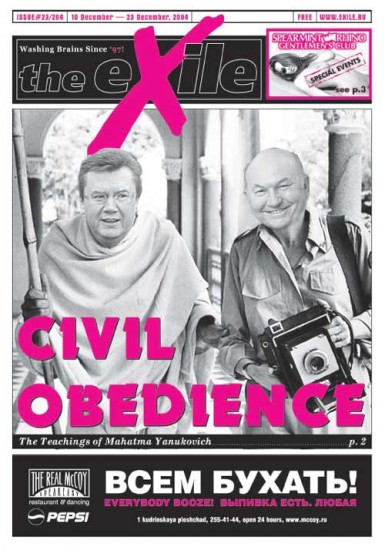

This review was first published in The eXile on September 4, 2004

We must remember the millions who died in the Soviet camps. Why? That nasty, nagging “why?” kept dogging me as I made my way through Anne Applebaum’s long (600 pp.) and well-researched history of the GULAG. If I hadn’t lived in Moscow from 2002 to 2004, I probably wouldn’t have had the nerve to challenge Applebaum’s mission, commemorating the victims of Stalinism. But one thing you learn in Russia, whether you want to or not, is that the Russians are not interested in this subject at all. And their lack of interest is strangely contagious, infecting even formerly avid fans of Zek literature like myself.

Before living in Russia, I used to wonder why none of the sons or grandsons of GULAG prisoners hunted down the thugs who tortured and killed their relatives. It happened in China, where descendants of those persecuted by the Red Guard tracked down and beat or even killed ex-Guards. And there’s an army of well-funded pursuers tracking down the few living ex-Nazis. Why didn’t Russians go after Stalin’s surviving executioners?

The simple, disturbing answer is that they’re not interested. And that bothers us. It’s not that the West cares very much about the Russians — either the millions who died, or the 140 million struggling to live in contemporary Russia. We’ve made our indifference to them pretty clear, over the past fifteen years.

Rather we need to believe that everyone shares our alleged dedication to the Christian-derived notion that we have to love everyone. And that means mourning, or at least going through the motions of mourning, every mass death.

So we wait for the Russians to start moaning and gnashing their teeth over the GULAG, as we would wait for a bereaved family to start keening over their loss. We’ve been standing nervously outside the Russians’ hut for over a decade now, waiting for those banshee wails to trigger our public tears.

And there’s been this silence — at first puzzling, then offensive. And at last, realizing that these shameless Russians aren’t going to start their own rites, we decided to do the job ourselves.

Thus Applebaum’s book was born. And it has the feeling of a belated, awkward funeral oration by one who didn’t know the deceased very well, but is driven by a deep sense of moral righteousness to perform the proper rites. To her credit, Applebaum knows and admits that the Russians themselves aren’t interested in commemorating the victims of the camps. She mentions that the only monument they have in Moscow is a single stone from the Solovetsky Islands. We lived a block from that stone, and for two years we walked past it nearly every day. I don’t recall seeing anyone take notice of it, even once. It sat there, splattered with birdshit, facing Lubyanka — completely forgotten. By contrast, the statue of Dzerzhinsky, though exiled to the Statue Garden by the river, is covered with curses and homage, just biding its time.

Anne Applebaum bears the sufferings of Stalin’s GULAG victims

In her final chapter, “Memory,” Applebaum attempts to account for the Russians’ indifference. She’s quite intelligent for a conservative, and surprisingly fair-minded for someone associated with a Tory rag like the Spectator. She even acknowledges that anti-Soviet rhetoric is soiled, in the minds of most contemporary Russians, by its association with the Gaidar kleptocracy, and offers a cogent summary of other possible factors:

“There are some good, or at least forgivable, explanations for this public silence. Most Russians… spend all of their time coping with the complete transformation of their economy and society. The Stalinist era was a long time ago, and a great deal has happened since it ended. Post-Communist Russia is not postwar Germany, where the memories of the worst atrocities were still fresh in people’s minds.”

The comparison to post-1945 Germany is the crucial one, the one by which contemporary Russia keeps disappointing and annoying righteous Westerners like Applebaum. This is yet another case of the “Hitler Standard,” by which the Nazis are the gold standard of evil, and the painful rehabilitation of Germany after 1945 the gold standard of recovery.

And of course this version of what happened in Germany in 1945 requires a suppression of memory at least as great as that involved in Russia’s apathy towards Stalin’s crimes. In the first place, it’s not the case that Germany’s crimes, in general, made much of an impression on “people’s minds.” Germany’s crimes against Russians, in particular, were little noticed nor long remembered in the West — despite the fact that the majority of the Wehrmacht’s victims were Slavs.

Most massacre victims are the sort of people not likely to be remembered. This is one of those almost-tautologies that’s still worth saying, like the old evolutionary biologists’ joke that most of us are descended from people who didn’t die before puberty.

And as another cynical French wit put it, we are all very good at bearing the sufferings of others.

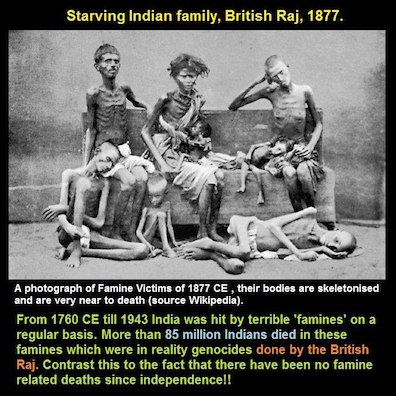

Only when a massacre is unusually dramatic and interesting, and/or involves people to whom we feel particularly close, do most of us feel anything. In other words, the Christian-derived premise that there is some Enlightenment moral sense in each of us, which reacts with instinctive horror at any mass suffering, is simply nonsense. There is no such sense — and a quick look at the archives of a Tory magazine like the Spectator, for which Applebaum proudly toiled, would reveal that fact a million times over. Ever hear of the “Black Hole of Calcutta”? Of course you did. That terrible overheated room in which some English prisoners were kept during the Indian Mutiny, so stifling that some of them actually died! Now, let’s do the math: what is the ratio of Indians killed during the British occupation to British prisoners stifled in the Black Hole? Few of you will have any idea, because those millions of dead never registered with us.

Applebaum would not have been capable of accepting a position with a vile publication like the Spectator unless her own consciousness contained at least one huge, highly adaptive amnesiac blob where all the crimes of the Empire should have been filed. So vast and horrific were these crimes, so long did they continue, that you could pretty much spin a globe, jab a finger at it blindfolded, and land on a spot where some Imperial force committed some sort of atrocity. (Unless, of course, you landed on ocean — though the Royal Navy would do its best to provide you with material even there.)

The crimes of history are optional. We mix, match and discard according to taste and convenience. It’s useful for Applebaum’s Tory backers to remember Stalin’s crimes because they can still use them to bash anyone who might want to beef up the National Health system with higher taxes. “Today an extra 1% VAT on my Jag convertible, tomorrow Kolyma!” is a very familiar war cry from these crusaders for human rights. Other massacres are dim stats, to be dredged up when necessary. Take, for example, all the tens of millions of dead in the Japanese occupation of China. They are rarely invoked in the West, because we don’t need them. The Japanese are thoroughly spent, neither a threat nor a bad example of anything we worry about at the moment. The Chinese are more of a worry, making the invocation of their dead a dangerous concession. And in the Tory mind, those dead are connected with ignominy: the surrender of Singapore without a fight, the sinking of the Repulse and Prince of Wales…and so it goes, with a huge number of tangential mental associations determining which of the billions of corpses clogging the earth will be dug up and flung at one’s opponents at any particular moment.

In this context, the Russians’ lack of interest in Stalin’s victims seems quite natural and healthy. It’s Applebaum’s arduous disinterment of them that ends up seeming forced, disingenuous and surprisingly dull.

John Dolan is co-host of the Radio War Nerd podcast. Subscribe here.

Don’t be a dick! Buy John Dolan’s comic memoir “Pleasant Hell” (Capricorn Press):

Buy John Dolan’s novel “Pleasant Hell” (Capricorn Press).

Posted: December 19th, 2013

This article was first published in The eXile on October 21, 2005

| A few days ago Viktor Yushchenko, the Ukrainian president and the hero of the Orange Revolution, received the Chatham House Prize for International Relations from the hands of the Queen of England. Some feted him for the Nobel Peace Prize, but after a series of political crises culminating in the resignation of his prime-minister — the “Glamour girl of the Orange Revolution” Yulia Tymoshenko — the notion soon became fairly ridiculous. It was quite appropriate in some sense — the consolation prize from the old musty monarchy, whose royal family became the laughingstock of the world in the last two decades, to the government of the “new East European democracy” which has already turned its country into a circus in just eight months. Ukraine suddenly became popular, even genuinely fashionable, last year. Even before the “Orange Revolution,” you could see this coming. For example, the Ukrainian pop-singer Ruslana won the Eurovision song contest in 2004, allowing the freshly “orange” Ukraine to host this contest in February 2005. (That time, its entry for the contest, a “revolutionary” song cheering Yushchenko, flopped — as usual, fashion changes fast.) When Yushchenko prevailed in last year’s election marathon, with passionate demonstrations, a sea of waving flags, and a tent city of half a million supporters, the Western media ecstatically declared that Ukraine had “finally” placed itself in the Western camp and “liberated” itself from perfidious Russian influence.

|

Posted: December 14th, 2013

This article was published in The eXile on December 10, 2004

DONETSK — Donetsk is a fascist city. I’m not using this term in the cheap way that it gets bandied around at a dinner table discussion between Republicans and Democrats. Donetsk actually is fascist. There is one party, people get beaten for opposition views, information is controlled, nationalist sentiment is enflamed with insane rhetoric about America/NATO plots to enslave Ukraine, and fear is the main motivating factor. It’s no coincidence that this is the side which Putin and the Russians are supporting. The “objective” Western press reports from there hide this fact by trying to “present both sides,” but I was just there, and there is no “other side.”

Just look at some examples of the fascist haze descending on Donetsk. Cable TV operators have actually stopped broadcasting opposition Channel 5. Media suppression of opposing views is so intense that it’s been driven literally underground — like the paper Ostrov that is being produced secretly. One local Yushchenko supporter told me about how her 9-year-old’s gym teacher asked the class who their parents voted for. “When the teacher found out that we were Yushchenko supporters, he made my son kneel in a corner for the entire class,” she told me.

When Salon, a Donetsk paper, reported two Sundays ago that a pro-Yushchenko rally was broken up before it even started, readers called to accuse them of printing lies — everyone here believes that it’s the Yushchenko protesters who have violent tendencies, even though there’s been a 30 percent drop in crime in Kiev since the protests started. What happened at that rally was that a well-organized group of men in track suits beat several people, including a Reuters photographer, and stole film and cameras — but officially, that simply didn’t happen. According to a spokesman from the Yushchenko headquarters, even an SBU operative (Ukraine’s FSB) recording the event for his own nefarious purposes was roughed up and had his video camera stolen.

This is part of a broader thug culture of Donetsk, part of a movement with Brown Shirts/Idushchii v Meste overtones. After a large rally last Monday, a group of 100 drunken thugs stood for hours shouting themselves hoarse and by 11pm, with no Yuschenko supporters to beat, several of them turned to fighting each other. While plenty of drunken people can be found among the protesters in Kiev (perhaps the most ecstatic participants in the revolution are the train station’s bomzhi, gorging themselves on free food and feeling safe now that the militsia has virtually disappeared), they aren’t aggressive or intimidating.

In Donetsk, they are frightening, unpredictable and above the law. Of course, that might just be Donetsk people acting normally. For example, there was a rumor that FT correspondent Tom Warner was beaten up by political thugs. As it turned out, he was simply robbed of his computer, phone and several hundred bucks by some common thieves. Another day, another crime.

* * *

Much has been made of eastern Ukraine’s support for Yanukovych, the pro-Russian prime minister who tried to steal the election. The Western and the Russian press both play up the issue, albeit for different reasons. Others, like my good friend Olya, who is an editor at a respected Ukrainian magazine, claimed everyone in Donetsk was just brainwashed.

What’s happening in Donetsk is the real key to figuring out what’s going to happen in Ukraine. The general situation in Ukraine has gotten plenty of coverage, but a brief outline of the facts is in order. Basically, Ukraine has always been divided into east and west, with the east Russian-speaking, heavily industrialized, and Russia-friendly; and the west Ukrainian-speaking, agrarian, and nationalist. Yanukovych is the east’s candidate, Yushchenko the west’s.

Almost all of Ukraine’s oligarchs are from the east or Kiev, and they almost exclusively lined up in support of Yanukovych, a Donetsk native. There are a few exceptions, notably Petro Poroshenko, the owner of car and candy factories and a ship-building yard. He also owns Channel 5, which was an invaluable tool in helping Yushchenko compete. In recent weeks, Channel 5 is the only Ukrainian channel to show news and propaganda 24 hours a day. A large part of the programming consists of watching Yanukovych’s team make asses of themselves. They often repeat a speech Yanukovych gave where he was gesturing with his fingers in the air, “paltsami,” a classic bandit gesture. Another favorite clip of theirs is of Yanukovych ally and Kharkov governor Kushnyarov gesticulating wildly and declaring, “I’m not for Lviv power, not for Donetsk power, I’m for Kharkov power!” Still, the biggest and most powerful clans are still behind Yanukovych, who is their man.

Yanukovych is a truly loathsome character. Most Ukrainians agree that if a more palatable candidate had been given the nearly unlimited access to “administrative resources” that Yanukovych had, he would have won handily. But Yanukovych twice served jail time in the Soviet Union, he has no charisma, and is obviously a tool of powerful Russian and Ukrainian interests. Yushchenko, on the other hand, is considered by most western Ukrainians to be something between Gandhi and Christ, while many people in the east worry he has it in for everyone who speaks Russian. Many people who voted for Yanukovych did so out of suspicion of Yushchenko, not because they like Yanukovych (except perhaps in his home turf, Donetsk).

While the country is relatively evenly divided, it’s a fact that Yushchenko would have won the election if it had been violation-free. Anyone who claims otherwise is either a fool or getting paid by the Russians. Even Putin, who called Yanukovych to congratulate him before all the votes were counted, recently said he’d be willing to work with any elected leader and seemed to acknowledge that there’d be a re-vote. Thanks to ballot-stuffing, Donetsk and the neighboring Lugansk oblast had by far the highest voter turnout in Ukraine (Donetsk had 97 percent turnout, of whom 97 percent voted for Yanukovych, and Yushchenko actually lost votes in between the first and second rounds of voting) and it’s on the basis of thousands of violations that the Supreme Court recently ordered a new round of voting. Channel 5 has plenty of footage of election observers getting the shit beaten out of them, and Yushchenko observers weren’t allowed anywhere near the polls in the Donetsk and Lugansk oblasts.

The blatant falsifications, combined with an extremely well-funded and coordinated protest movement, have brought us where we are today, gearing for another round. The protests have come under fire as an American-funded coup, particularly in the Russian media. And there’s some truth to it — the US has been bringing in Serbs and Georgians experienced in non-violent revolution to train Ukrainians for at least a year. One exit poll — the one finding most heavily in favor of Yushchenko — was funded by the US. The smoothness and professionalism of the protest, from the instant availability of giant blocks of Styrofoam to pitch the tents on to the network of food distribution and medical points, is probably a result of American logistical planning. It’s certainly hard to imagine Ukrainians having their act together that well. The whole orange theme and all those ready-made flags also smack of American marketing concepts, particularly Burson-Marstellar.

But the crowds in Kiev, which can swell up to a million on a good day and are always in the hundreds of thousands, are there out of their own homegrown sense of outrage, not because some State Department bureaucrats willed them there. The meetings that happen every day in virtually every city in Ukraine (and in literally every western Ukraine village) are not the result of American propaganda. Rather, they are the result of the democratic awakening of a trampled-on people who refuse to be screwed by corrupt politicians again.

While you wouldn’t know it by watching Russian TV, maybe the only two cities in Ukraine where there are not Yushchenko rallies that outnumber the Yanukovych rallies are Lugansk and Donetsk. According to my friends in the heavily Russian Kharkov, for example, active Yushchenko supporters outnumber active Yanukovych supporters four to one. One reason why Lugansk and Donetsk are an exception is because every time Yushchenko’s people try to organize a rally there, they get beaten. Another is because the vast majority of those two regions really do support Yanukovych. So what gives?

* * *

For hours after the pro-Yanukovych rally ended on Monday, November 29, a parade of some twenty cars raced up and down Ulitsa Artyoma noisily demonstrating which candidate they preferred. Judging by many of the cars in the procession — a couple of new Mercedes, a novel Smart Car, other inomarki, and a custom-painted Lada souped up for drag-racing — the drivers were members of the Donetsk elite. Judging by the whoops and screams of the passengers, many of whom hung outside the sunroofs and windows waving blue flags, the paraders were quite young and totally wasted.

Unfortunately I’d just arrived in Donetsk that evening and only caught the tail end of the rally, so I didn’t know what’d gotten them so riled up. I later saw an excerpt of it on Channel 5, where Yanukovych’s wife Ludmilla said that everyone involved in Kiev’s protests was in a drug-induced haze. “On Maidan [where Kiev’s protests are centered*, they’re distributing oranges injected with narcotics that people eat, and everybody wants more, and nobody can leave the square.” Perhaps more shocking, no one in Donetsk even blinked at what she said. (And on Kremlin-controlled Russian TV, they repeat the same lies about the protestors either being “psychologically unhealthy” or drug addicts.) Calling the hundreds of thousands of protesters that come out daily in Kiev the product of oranges pumped with drugs is not just absurd, it’s stupid. And yet in Donetsk, they were buying it.

But the hoods with nice cars cruised, horns blaring until well after 11, alternately driving slowly to build up a column of traffic behind them and then accelerating, speeding over the limit, disregarding such niceties as red lights and traffic laws. The GAI were absent because presumably the action was approved from up high, and the punks no doubt had powerful parents. One of the newest Mercedes — an S Series — was equipped with a loud speaker, used by some young thug to startle unsuspecting pedestrians: “Are you for Yanukovych?” Everyone said yes, myself included.

Of course, horns these days are a popular means of expression in Kiev as well. But it’s not the same group of cars, driving in circles and intimidating people. Instead, drivers honk to express solidarity with the “orange” protesters and drive on to their destination. It’s spontaneous, an outburst of a new sense of freedom and empowerment. There’s even the occasional blue-bedecked car that is allowed to pass unmolested, although God save anyone dumb enough to wear orange in Donetsk.

In Donetsk, there are blue ribbons and flags, “Ya-Nu-Ko-Vych” chants and honking horns, daily meetings and concerts, all mimicking the protests in Kiev. But it is the opposition tactics that Yanukovych’s hacks have not mimicked that are more striking: no tent city, no out-of-towners (except the press-corps), no information distribution, no sense of debate, no tolerance, no grassroots organization. The Donetsk demonstrations are just displays of top-down managed “democracy,” and the population there is passive enough to swallow it.

* * *

The Tuesday rally, which I witnessed in full, was like watching a farce of a Nazi rally. This time they introduced Ludmila Yanukovych but made sure not to give her the mike, lest she say something as ridiculous as her spiked-orange theory. However, the other speakers weren’t much more sane. One speaker after another spewed venomous anti-Kiev, anti-western Ukrainian, and anti-American rhetoric at the crowd of several thousand. One of the more famous, Natalya Vitrenko, is sort of a Zhirinovsky without the slapstick element. Vitrenko argued that the US planned to colonize and enslave eastern Ukraine and would use NATO as its muscle. Another speaker warned that east Ukraine would beat back the Americans like they had the Germans, and reminded the audience that western Ukraine welcomed the Nazis with bread and salt, keeping in the theme that Yushchenko’s the fascist here. Some of the other arguments were just silly; one doctor said that Yushchenko was destroying the nation’s health by forcing students to spend long hours in the cold, thereby causing a public health crisis (a line echoed on Russian state television). Another said under Yushchenko people would be jailed for speaking Russian and that the “orange plague” was a terrorist organization. Another popular theory was that western Ukraine was planning on raping the riches of the east and only regional autonomy could save them. Every speaker was fear-mongering and totally detached from reality.

Everyone in Donetsk repeats the same figures and statements obsessively. 15 million voted for Yanukovych, he is the legitimate president, and Yushchenko is an unchecked fascist. People in Kiev are brainwashed and undemocratic; Russian-speaking centers Odessa, Kharkov, Dneipropetrovsk and the Crimea will leap at the chance to form a breakaway republic with them; American money is behind everything. Funny they never mention a word about Russian funds used by Yanukovych, although estimates of Russian contributions reach up to $300 million.

One of the great things about “orange” Kiev is that everyone everywhere is engaging in political dialog, arguing about what’s happening, what it means, and predicting how things will turn out. In Donetsk, everybody uses the exact same descriptions and expressions, because they’ve all been brainwashed. And they’re defensive about their beliefs, even on their home turf.

People here freely admit that Yanukovych is a dishonest politician with unsavory connections, saying “Yes, he’s a crook, but he’s our crook.” One guy I asked how he felt about Yanukovych’s jail past replied, “So what? I’ve been in jail, too.” The guy who said that had a valid point — Donetsk has always been a bandit city since the time the Soviets populated the region’s rich mines with ex-cons. There’s nothing exceptional here about having done time.

It’s clear by the overwhelming number of expensive boutiques, restaurants and casinos that Donetsk has a larger bandit class than most places. It certainly isn’t miners spending their pay in these places. Ukraine’s wealthiest man, Rinat Akhmetov, is from Donetsk and took over his empire from his relative, Oleg Grek (Oleg the Greek), who was shot dead in the city’s stadium during the bloody gang wars of the mid-90s. Akhmetov’s behavior mirrors the city’s values; when he wanted a new house, he simply seized a well-loved playground in the center and built a fortified castle-like compound, a la Tony Montana. Actually, it’s not that dissimilar to how they planned on installing Yanukovych.

Everyone in Donetsk, repeating the propaganda, will also tell you that they’d never use political beliefs as an excuse to do nothing, like the lazy people of Kiev, and that people here continue to work through the crisis. It’s well-known that Yushchenko’s people pay 400 hr. (over $70) a day to hire Donetsk protesters, but officially, no-one would ever sell out. For the record, the average monthly salary in Donetsk is 784 hr. People absolutely refuse to believe that there was vote fraud. Actually, they simultaneously argue that there was none and that it was no worse than the fraud in western Ukraine, as if that unsubstantiated claim is justification for vote-rigging. One of their favorite points is that coal miners started receiving their pay and factories started working when Yanukovych was governor. In fact, wage arrears in the Donetsk oblast are by far the largest in Ukraine, making up 28.6 percent of the country’s total. In second place, with 13.2 percent of the total, is Lugansk oblast.

Revisionism is rife here. Donetsk governor Anatoly Bliznyuk’s denied that there had been talk of separatism at a congress in Severodonetsk two days earlier, yet the congress’s words and actions had already been reported. Politicians like Bliznyuk only started backpedaling when Yushchenko threatened separatists with arrest.

The people in Donetsk simply parrot what they are told. On Monday, November 29th, the day after the Severodonetsk conference, several people told me that there were two options: separation or war. On Tuesday, when Kuchma and Yanukovych seemed to come out in favor of a revote in Donetsk and Lugansk, people here were for the revote.

Meanwhile, back in Kiev, it’s hard to imagine a more positive vibe. Seeing the process of nation-building develop in front of my eyes was an amazing experience. Ukrainians have always had a more mellow character than the Russians, and it shows through in their revolution. The stuff you read about protesters eye-to-eye with storm troopers is lies — there’s actually four lines of massive pro-Yushchenko miner- and peasant-types standing on shipping crates to keep protesters from direct contact with the militsia. The feeling on the street is festive.

Babes are everywhere, and it’s the only place I’ve ever been where a pickup line is totally unnecessary. If she’s wearing orange, you’ve got a common language. While some people have wild delusions of EU membership in five years or the end of corruption that will never happen, on the ground in Kiev it does seem like democracy and free press is achievable.

Back in Donetsk, there is no trace of irony when they describe Kiev’s demonstrators as fascists, zombies, censors and separatists, words they ought to self-apply. But it’s exactly this passivity that makes the threat of separatism so hard to take seriously.

* * *

So what is really going on in eastern Ukraine? Is it dangerous?

All that’s really happening is that the authorities in Donetsk are cynically manipulating the people out of fear for their own positions. While the meetings attract old and young, all of who come at their own accord, they can hardly be called grassroots.

People in Kiev have made it clear that they’ll stay put until they win, and they certainly would be out in force even if there weren’t speeches and music. But would people here come out in Donetsk the authorities didn’t organize meetings? From what I saw, no way.

What’s happening in Donetsk is simply the panic and hysteria of a corrupt regime desperate to cling to power. They’ve proved that they are able to mobilize large groups of people to defend their interests, but those crowds have no life of their own. Create a situation which the local authorities find acceptable and the protests will melt away. Give the local authorities a guarantee of immunity from prosecution and continued control of their fiefdom and they’ll abandon the separatist rhetoric.

The people of Donetsk might not be happy with that development, but then, they’re used to being betrayed and cheated by their leaders. In time-honored tradition, they’ll grumble about corruption and do nothing about it. Unlike the rest of Ukraine, they haven’t experienced the euphoria of living free, and until they do, they’ll have no way to vent their outrage.

This article was published in The eXile on December 10, 2004

Posted: December 2nd, 2013

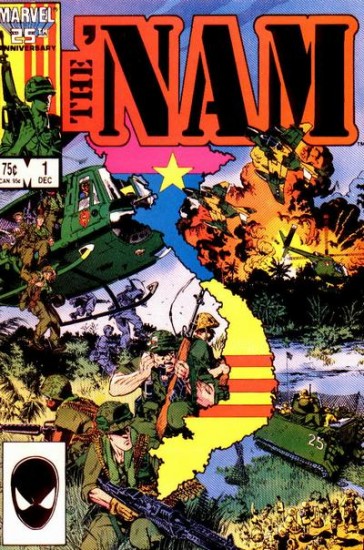

Mel Gibson’s Vietnam movie We Were Soldiers just hit New Zealand, so I’ve had to deal with endless commercials of that sagging beagle-face of his, carefully smeared with artificial dirt and smoke, rallying the troops in a laughable attempt at a Southern accent. Having seen The Patriot, featuring Mel doing a similarly rotten Carolina accent as he ran around chopping up Redcoats with a teeny little tomahawk, I think I’ll skip his remake of Vietnam.

But it did send me back to reread the book Mel bought to use as the basis of the film: We Were Soldiers Once…and Young. It seemed like a good occasion to review some of the innumerable Vietnam memoirs I’ve bought over the years.

Yes, chillun, I am old enough to remember that once upon a time, nice people didn’t even want to talk about Vietnam, let alone read about it. Now how did it git so’s they don’t hardly wanna talk ’bout nuthin’ else? Gather ’round the fire and I’ll tell you all about it.

Avoiding Nam was pretty much a fulltime job for sensible Americans of the 70s. It didn’t look like fun yet — not when it was actually happening. That took several years and about a thousand war memoirs. At the time, it looked like a remarkably uninteresting war, with wretched losers from inland America standing around the paddies twitching nervously, wondering whether the water buffalo in the next field was going to whip out a Kalashnikov and start shooting.

That changed very slowly. The first book to make Nam seem cool was Michael Herr’s Dispatches. This was the first Nam book taught at universities (I encountered it in a course at Berkeley). Herr wrote as one of the college boys who didn’t fight. He was there to watch, write, and make a name for himself. He wrote guilty erotica, and spoke for the smart guys who got themselves deferments but always wondered what they would’ve done if they’d gone: “You know how it is, you want to look and you don’t want to look. I can remember the strange feelings I had as a kid looking at the war photographs in Life…”

Since the deferred guys were the core of the teaching pool at most American universities, they tended to assign Herr’s book, and it became one of those “instant classics” which make it more for demographic than artistic insights. Herr’s book was a first draft of Apocalypse Now, with Hendrix soundtrack and quick cuts between cool gore and Saigon lies. It doesn’t read particularly well now; there’s too much caution there, like someone trying to do Hunter S. Thompson after halfheartedly inhaling one tiny line of speed. But then that’s always the way to crack the upscale porn market: just a little whiff of the really hard stuff, enough to grab the safe people. After all, the safe, guilty males of the Nam era had two advantages over the ones who went: they had graduated to teaching jobs and could force large numbers of students to buy the book — and they were alive.

Herr’s book came out in ’77, two years after the fall of Saigon. It was a while before anybody wanted to hear from the losers who’d actually gone and fought in Nam. It took a lot of concerted lying, in films like Deer Hunter, to erase all those images and persuade the home folks that the enterprise had been a noble one.

In strictly literary terms, this great lie was of some benefit, because there are few genres as rich as the war memoir. Virtually anyone who saw combat and has a decent memory can write a decent book about it — and Vietnam, a war characterized by thousands of small skirmishes, was richer in incident and gore than an inner-city basketball tournament. When next you hear that rough voice asking, “War — what is it good for?”, you tell it: “First-person memoirs, that’s what!”

By 1981, the memoirs were coming fast. The first and in some ways still the best was Everything We Had, a collection of oral reminiscences by 33 vets who’d done everything from nursing the wounded to slitting throats with Bob Kerrey and his pals. I’d still recommend this book as a starter-kit for the prospective Nam fan, because the 33 voices offer something for virtually everyone. Parts of the book are very funny, as when Gayle, the cute li’l nurse, recalls her answer when asked if she’d serve on a ward for Vietnamese casualties: “And I said, ‘No, I would probably kill them.’ and she said, ‘Well, maybe we won’t transfer you there.'” And they say the Army has no heart!

By the early 80s, it was not just cool to’ve served in Nam; it was glorious. It was, in fact, the only sort of martial glory available (Grenada didn’t quite carry the same “cachet,” as they said in the Reagan era.) Every Vet still alive and compos mentis — and some who weren’t — headed for that early-model KayPro or Northstar keyboard to turn his ranting into cash. They were a little confused at first, having been shunned and pitied as they dragged their way from halfway house to detox to medium-security institution…but slowly a canny ambition shouted down the voices babbling in their addled heads with the news that the war stories which had driven the wife and kids to move out with no forwarding address were now box-office boffo.

And damned if many of them, fingers trembling on the keyboard, one hand on the Jack Daniels or rolled-up twenty, didn’t hunt-and-peck out some quite good books.

This high literary output was a delayed gift of the utter lack of strategy which doomed the American enterprise in Vietnam: a war which consisted largely of sending small contingents of infantry out into the jungle to find the enemy, usually by getting ambushed, is bound to be a military disaster — but equally bound to produce an extraordinary number of fantastic combat tales. As Walter puts it in Big Lebowski: “Me and Charlie, eyeball to eyeball.” Throw in the treachery of the South Vietnamese, the social and racial bombs going off non-stop back home, the feeling of abandonment, the music — greatest soundtrack of any war ever — and you had the elements of better stories than more intelligently-conducted wars could ever yield. (If there were any true aesthetes worthy of Oscar Wilde’s mantle, they’d’ve agitated for the continuation of the war at all costs. Alas, dreary Utilitarian ethics have conquered us so thoroughly that not a single voice urged the continuation of the war as the greatest performance art of the century.)

I’ve read a dozen of these memoirs, and enjoyed almost all of them. They come in all flavors. There’s the raunchy defeatism of F. N. G., which describes a “fuckin’ new guy” entering an infantry squad after Tet, when the Americans had pretty much given up trying to win and were fighting a strange, highly mobile but essentially defensive war. Then there’s Once A Warrior King, describing one very conservative Virginian’s relatively straightforward war, working with a fiercely anti-VC village in the Delta. This is Greene’s Quiet American told by the quiet A. himself, as it were — and he tells a good story. It’s the food I remember best, in that one: the long descriptions of roasted rat with fish-sauce. That’s one of the delights of war and prison memoirs: you can count, in these solidly grounded stories, on some excellent descriptions of meals good and bad. (The POW memoir, combining the genres, often yields the most mouth-watering descriptions of all; if you want a book full of the delight of eating, read Brendan Behan’s one good book, Borstal Boy.)

The best of all these might be Chickenhawk, the story of a helicopter pilot who was, as Martin Sheen says of “Chef” in Apocalypse Now, “…wound up a little too tight for Vietnam.” Robert Mason, the pilot-narrator, takes the reader in and out of so many LZs, hot, cold and medium, that you develop a veteran’s wince everytime his slick starts descending toward the purple smoke.

One of the many delights of Mason’s book is that it describes the battles for the Ia Drang — the same campaign glamorized in We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, the book Gibson filmed. The campaign, which is depicted as a noble, though doomed, strike for freedom in We Were Soldiers…. doesn’t come off so well in Mason’s memoir. In fact, he and his fellow pilots seem to have done something the generals in charge of the operation didn’t do: read the books about earlier French campaigns against the Viet Minh in that same valley. Mason and his drunken buddies end up predicting the failure of the campaign while their superiors are still sending home the sort of communiques which did so much to cement the American Army’s reputation for…er, “emphasizing the positive,” let’s say.

But Mason’s topper, his most brilliant passage, comes at the very end, in the epilogue summarizing his messed-up return to civilian life. Here’s the superb two-paragraph conclusion, describing his next move after the early drafts of his Nam memoir had been rejected and he’d failed in everything he tried since getting back to The World:

“What did the desperate man do? I can tell you that I was arrested in January, 1981, charged with smuggling marijuana into the country. In August 1981, I was found guilty of possession and sentence to five years at a minimum-security prison. I am currently free as of February 1983, appealing the conviction.

“No one is more shocked than I.”

Just roll that last sentence over on your tongue. “No one is more shocked than I.” Now there is a meal. Even the fussily correct grammar, that annoying “…than I” rather than the colloquial “than me” or “…than I am”; so perfectly droll, such a change from the Nam dialogue in which every other word is “fuckin'”. And the grand historical irony, that the junked helicopter jock should become desperate enough to sell his one skill to the only people who wanted it, the drug dealers, designated New Enemy of the Reaganites. And the timing! Mason’s manuscript got four rejections in the years leading up to 1981, when the memoirs started appearing. A little later, and he’d’ve been cool. But that would have been disastrous. To go to prison for piloting a helicopter full of drugs, albeit unworthy boring drugs like marijuana, even as that great war-dodging hypocrite Reagan shoved his leathery grin in front of the flag — ah, It’s a fate better than death.

This article was published in The eXile on June 28, 2002

Posted: November 30th, 2013