Issue #14/95, July 20 - August 3, 2000

A

Real Journalistic Whore

A

Real Journalistic Whore

It was way past deadline here at the eXile offices this past Wednesday night when we realized we were in a bind. We still had holes in the paper, but no one in the office had any ideas left in his head. Lots of staring blankly at computer screens going on, lots of "just one beer" beers turning steadily into five or six, lots of un-laid out pages piling up on our designer's desktop. The holes needed to be filled, but how? The situation seemed hopeless—until, late in the evening, we came up with a plan. We called a whore.

See, the way we figured it, if we called a whore and paid her sixty bucks or so, we'd own her for the hour. And in that hour, we could do whatever we wanted with her. We could rear-entry her, DP-and-Wendel her, or even—and this is the beautiful part— make her sit down at a desk and write 600 words for page 4.

We called a service—we won't reveal which one. Having heard multiple voices in the background over the phone, the agency sent a single bodyguard with her, the usual protection against probable gang-rape. The guard peered into our doorway, determined that the number of males was a satisfactorily sober less-than-fifteen, and introduced us to our gang-rape-expectant freelancer. She turned out to be a smallish, plump girl of 18 named Tatiana, with a vague resemblance to Sally Struthers.

The eXile editors came to the door and explained the situation.

"Listen," we said. "We're in a bind. We're a newspaper and we're putting out the issue tomorrow... and we have serious writer's block. We've got a hole in the paper, you see? So we want you to write an article."

The "guard"—a smallish, narrow-shouldered Russian in dirty jeans and a fake black Versace shirt— looked at us carefully. "Write an article?" he said. Then, glancing down at our beltlines, he added: "And then what?"

"And then nothing," we said. "She writes the article and leaves."

The guard paused, scratching his unshaven chin and staring dully ahead. A minute passed. Finally he smiled and turned to the whore. "Nu, chto, dorogaya," he said. "You're gonna write."

Tatiana

stared at us, terrified. "What do I have to write?" she asked.

Tatiana

stared at us, terrified. "What do I have to write?" she asked.

"Yeah, what does she have to write?" the guard asked, the possible negative consequences apparently just occurring to him.

"Anything she wants," we said. "She can write about her dog. The weather."

He looked at her and shrugged. "There it is," he said. "Just write something. And call when you're done."

He pushed the girl gently inside and left. We grinningly regarded Tatiana. She was clearly unused to wearing high heels, and her stretch skirt was way too tight for her slightly too-bulging haunches. She had a friendly round face, but the bent, discolored teeth of and old man. At our invitation she waddled doe-legged, heels clicking, into our secretary's office. Once she was firmly seated behind the fax machine we handed her a pen and a piece of typing paper.

"Write," we said.

She looked up. "Do you have any paper with lines?" she said. "I have trouble writing without lines."

We found a graph paper notebook and tossed it in front of her. She sat staring at it mute. We left her alone and went about laying out the rest of the paper. Then, after five minutes, we poked our heads in, and she was still sitting in the same position. Another five minutes passed and the situation was the same. Around that time the phone rang; it was her Madam.

"Is Tatiana there?" she barked.

We handed the phone to Tatiana, who cupped the receiver. "Yes, everything's fine," she said. "No, it's not like that. They want me to write an article... No, I don't know what kind. Any kind... Is that okay? I don't know, it's some kind of newspaper... No, they're okay, I guess, normal-looking guys...It's okay? Okay. I'll call soon. Goodbye."

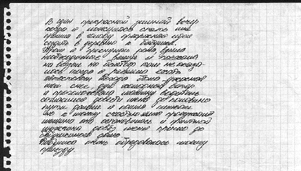

Poor Tatiana turned out to be something less than the next George Sand undiscovered. It wasn't until a good ten minutes after the Madam called, by which time we had exhaustively determined through conversation that Tatiana had neither hobbies, pets, interesting acquaintances who came to mind, or interesting childhood experiences she could remember—by which time we'd determined, in fact, that she scarcely remember anything at all—that she finally set down her pen to paper. The resulting story turned out to be a sad tale of a little girl who goes to visit her grandmother in the country and runs out of cigarettes. Here it is:

My Story

By Tatiana

On one fine winter evening as I went to bed the excellent idea came to mind to go visit my grandmother in the country. I woke up early in the morning, packed the necessary things, and went to the train station but couldn't get a ticket so I decided to hitchhike. The weather that day was terrible, it was snowing, and there was a very strong wind and I caught a ride but the driver could only take me halfway and so when we got there I got out and started to walk.

[This next part was added post factum during an oral edit].

It was cold. It was snowing. It snowed and snowed and snowed. I was very cold and didn't feel all that well. Finally to my relief a car pulled up and the driver agreed to give me a ride all the way to my grandmother's house. The driver was a young man and kind of good-looking. He had brown hair and was nice. Anyway he drove me all the way to my grandmother's house, which is in the Moscow oblast, about two hours or maybe more from Moscow.

[We return to the original narrative.]

Where my grandmother lives it is very remote and products are only delivered rarely, on a truck that comes once a week. Unfortunately for me when I arrived a quickly ran out of cigarettes, and the truck wasn't due for another three days. I waited and waited until finally the truck came. I went to the back of the truck with my money in my hand. I was going to get cigarettes!

"Give me a pack of Yavas, please," I said.

"We don't have any Yavas," the man said. "All we have are Primas!"

[Eds. note At this point, Tatiana tried to stop her narrative. We failed to understand that this was the dramatic climax of the story, that the truck only had papirosi cigarettes. "Okay, all they had were Primas," we said. "And then what?" She looked at us. "And then what?" she said, and went on:]

Well, of course, I didn't buy the Primas, because they're horrible cigarettes. So in the end I spent three whole weeks at my grandmother's house without cigarettes. Then, finally, I went back to Moscow, where I bought cigarettes.

[The end.]

Oddly enough, Tatiana stayed in our office, sitting patiently, far longer than the hour we'd paid for—about two and a half hours in all. She shamed us by quietly explaining that she didn't like to leave before her job was done. Both sides were apologetic and a little regretful when it came time for to leave. "I'm not used to this kind of thing," she said.

"Don't worry about it," we said. "It's just journalism. Every reporter in the world feels the same way you do every day."

She left. It was 4 a.m.

Cards |

Links |

The Vault |

Gallery |

Who? |