This review was originally published in The eXile in April 2004

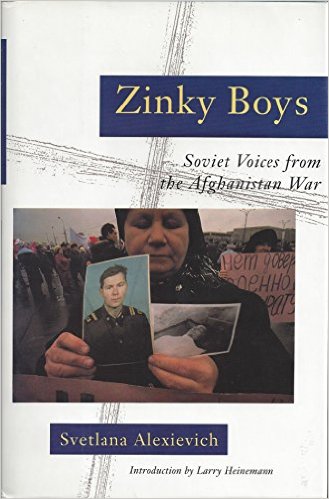

In a review of several Vietnam memoirs, I asked readers for information on oral histories by Soviet soldiers who served in Afghanistan. Several mentioned this book, Zinky Boys, published in English translation 12 years ago. As far as I know, it’s still the only oral history by Afghan vets available in English.

Zinky Boys is clearly modeled on the many bestselling Nam memoirs. The introduction is written by one Larry Heinemann, a Vietnam vet who visited Russia to talk to Afghan vets. His introduction is the worst thing in the book, full of silly blather about how democracy is sweeping over Russia and how the Afghan vets will no doubt play a part in its victory.

Yet, for all the superficial resemblance to Nam books, Zinky Boys is unlike any American war memoir. The differences are easy to spot, but hard to explain. Some you’d expect: for one thing, the editor can hardly make a point without quoting Dostoevsky, Lermontov, Berdyayev or Tolstoy. You don’t find that sort of literary figure quoted much in the typical Nam memoir. Hendrix is about as close to high culture as they usually get.

A far more radical and intriguing difference is the prominence of women in the book, starting with the fact that the editor is Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian journalist. I can’t think of a single Nam memoir edited by a woman. It may be that Russian women feel entitled to speak about war more freely than American women simply because Russian women took a huge role in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945. In fact, one of the Afghantsi who tells his story here mentions that his grade school was once visited by a WW II vet nicknamed “Mother Sniper,” whose claim to fame was that she had killed 78 Germans during the war. (She scared him so much he was ill for a week.)

But the women who speak here really didn’t enjoy Afghanistan much. As one of them says frankly, “I wanted to be in a war, but not like this one. Heroic World War II, that’s what I wanted.”

Zinky Boys focuses, much more than any Nam memoir I know, on the dead. Even the title refers to the closed zinc coffins in which Soviet dead were sent home. Grieving families were forbidden to open the coffins, and many of the soldiers’ mothers interviewed talk about how awful it was, never knowing whether their dead son was actually in that zinc box:

“They brought in the coffin. I collapsed over it. I wanted to lay him out but they wouldn’t allow us to open the coffin to see him, touch him…Did they find a uniform to fit him?…Now I just want to be in the coffin with him. I go to the cemetery, throw myself on the gravestone and cuddle him ….”

Many of the mothers interviewed went insane after their sons’ deaths: “His mother went mad two days after the funeral. She ran to the cemetery at night and tried to lie down with him.” Does the emphasis on grieving mothers reflect simply the author’s special interest, or does it imply that the mother-son relationship is more important in Russian than American culture? Some of the interviews suggest that this is by far the strongest bond in Russian women’s lives: “Yura was my eldest son. A mother shouldn’t admit it, probably, but he was my favorite. I loved him more than my husband and my younger son.”

Yura’s mother’s story is one of the grimmest in the book, because she blames herself — with some justice — for his death. Theirs was a “good family” in Soviet terms. And like a good Soviet son, Yura enters officers’school, then tells his mother, “All those high ideals you taught me, they don’t exist. Where did you get them all from?” His mother keeps up the lie: “I told him yet again that our Soviet life was wonderful and our people were good.”

Inevitably, Yura ends up dead. And his mother, a born storyteller, tells how she prayed that it was her other son, Gena, who was dead: “I asked them, ‘Is it Gena?”No, it’s Yura,’ one of them said, very quietly.” She tells this story against herself. Now that’s horror.

Not all the women interviewed in Zinky Boys were entirely unhappy in Afghanistan. The Russian proverb, “War is a stepmother to some and a mother to others,” applies even to those women who served. One who volunteered for Afghan duty as a civilian employee has some of the best war stories I’ve ever read. She starts out fending off attempted rape by every officer she meets. (No Afghan women feature in the book in any sexual or romantic context. You get the sense that, unlike US GIs in Vietnam, Russian troops didn’t find the local women attractive — not to mention the fact that, unlike the GIs, the Russian troops were even poorer than the Afghans, making prostitution unprofitable.)

Then she finds a man she likes: “…I found…love? That’s not a word much used over there.” But if it wasn’t love, it was something intense enough to make her shield his body with her own when they come under fire. The narrator boasts that “…when we got back [to base] he wrote his wife about me. He didn’t get any letters from home for two months after that.”

It’s strange how little wives and husbands figure in these stories. Again, I’m comparing these stories in my own provincial, ethnocentric way with the Nam memoirs I’ve read. In those books, if anyone else is mentioned it’s usually the wife or longterm girlfriend. That’s not the case here. There are lovers, who seem to attain, however briefly, the status of mothers in the narrators’ lives. But when those lovers become spouses, they seem to fade into the background; only the mother/son bond remains.

The soldiers’ own stories of combat in Afghanistan don’t seem nearly as vivid as their mothers’ accounts of meeting the zinc coffins. Is this the result of editing by a female, antiwar writer, or does it mean Russian men are reluctant to tell war stories? I can’t believe it’s hard to get vets of any war to start trotting out the war stories, so I’m inclined to think that either the editor suppressed them or, perhaps, Afghan battles just didn’t make good stories.

That may well be it, because most of the casualties seem to have been inflicted by landmines. And mines just don’t make very good war stories: boom, you’re maimed.

Or maybe Russians just didn’t have time to perfect their war stories, because they were trying to deal with the chaos that soon followed the end of the Afghan campaign. Maybe that’s the biggest Nam/Afghan memoir difference: the Vietnam War struck a country at the peak of its power and wealth. In a real sense, America could afford to listen to the Nam vets’ accounts, even savoring the exotic gore they offered to a country swaddled in comfort. The Afghan vets’ stories were lost in the far greater catastrophe playing out in the homeland. The USSR they fought for ceased to exist a few years after their Afghan war ended. Maybe the best story in Zinky Boys is by an ex-artilleryman distracted from his own case by that of another victim of the collapse of “the Motherland”:

“There’s an old woman living in our block…As a result of all these articles nowadays, the revelations, exposes…she’s gone mad. She opens her ground-floor window and shouts, ‘Long live Stalin! Long live communism — the glorious future of all Mankind!'”

The grief of aging women — that’s the biggest impression you take from Zinky Boys. Why the prominence of mothers in this war book? My guess, and it’s no more than a foreigner’s wild guess, is that gender roles are so sharply, excitingly polarized here that only a woman could negotiate the shame of telling the misery of those who served in a Russian defeat, since her gender has far more license to explore grief and sorrow. Hence, perhaps, the soldiers’ mothers’ horror at not being able to embrace their sons’ bodies: a vital part of their role had been denied them, locked up in those closed zinc coffins.

John Dolan is co-host of the Radio War Nerd podcast. Subscribe here.

October 8th, 2015 | Comments (1)