The hills are alive with the sound of RPGs

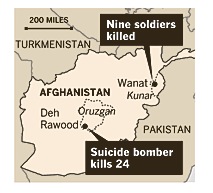

After six years of ignoring Afghanistan, things have gotten bad enough to force American officials to pay attention. For the past two months, U.S. casualties in Afghanistan have been higher than in Iraq. And on July 13, Afghanistan definitely got everybody’s attention when nine U.S. troops were killed in what Wikipedia is now officially calling “The Battle of Wanat.” Three days after the battle, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), the U.S.-dominated military force running the country, announced it’s abandoning Wanat completely.

Let’s start with a close-up of the battle, then zoom out to the overall situation in Afghanistan. Wanat is in Kunar Province, along the border with Pakistan. It looks a lot like Northern Wyoming: mountain country, steep slopes with pine forests running down to fast, cold rivers. Some of the photos I’ve seen from Kunar seem like stills from “The Sound of Music” or “Heidi,” only some prankster has Photoshopped in a platoon of soldiers in desert camouflage.

The outpost that the United States had just set up in Wanat was supposed to disrupt Taliban supply lines from Pakistan. Instead, it became a tempting target for the local guerrillas, just like hundreds of other remote forward bases in other rural guerrilla wars from Southeast Asia to Algeria. Guerrillas usually avoid open combat with conventional forces, but when they do attack in force it’s usually against the smaller, more vulnerable forward bases. The Wanat base was a very tempting target because it was still under construction.

It’s not so easy to be sure what actually happened in the battle there on July 13. A big Taliban force — big by guerrilla-war standards, meaning several hundred — was able to mass outside the base without being detected. They attacked with rocket-propelled grenades, mortars and rifle fire, managed to take part of the base, and then either withdrew or were forced back into the town of Wanat, where the fighting continued in the ruins. The NATO troops had massive air support, and faced with that, the guerrillas dispersed into the hills. Then, three days later, the U.S. forces, who have de facto command of southeastern Afghanistan, also withdrew. Officially Wanat is now in the hands of the Afghan police, but that’s a joke.

You can tell how ridiculous that claim is by looking carefully at the casualties from the battle. This is a good example of how to read war news carefully, how to read between the lines of standard press coverage. It’s almost like a story-problem for war nerds. Here are the figures: There were 70 defenders in that base, 45 U.S. troops and 25 ANA (Afghan National Army) troops. That’s about a 60/40 split. So if both groups fought equally effectively, you’d expect more than a third of the casualties to be from the ANA. But that’s not the story the casualty figures tell you. Every defender who died was American; no Afghan troops died. Three-quarters of the wounded were also American, only four out of 19 were Afghan. What that tells you is that the ANA didn’t fight. They left it to the Americans. That’s a pattern you often see in guerrilla wars: The locals fight very hard against the occupiers, but not very well for them. So in Vietnam, the Viet Cong fought like demons and the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) barely fought at all, even though they were from the same ethnic background.

There are a lot of very familiar patterns in this story. If you zoom out from Wanat and look at the bigger situation in southern Afghanistan, you’ve got the classic ingredients for a long, bloody guerrilla war: a big ethnic group on both sides of an artificial border, difficult terrain, and dirt-poor peasants with a long tradition of fighting just about everyone who comes along, from Alexander the Great to the 19th century British. The Pakistani/Afghan border is 1,500 miles long, and the people living on both sides of it are Pashtun, the biggest ethnic group in Afghanistan and the support base of the Taliban. The Taliban started as a Pashtun resistance to the Northern Alliance warlords, mostly Uzbeks and Tajiks, who took power after the Soviet pullout in 1989, and the Taliban is still mostly Pashtun. The reason you don’t hear so much about the ethnic angle is simple: Neither side wants to push that angle in its propaganda. The Taliban would like to claim to be defending Islam, and the Americans are happy to go along with that, so they can say we’re fighting Islamic terror. But the fact is that the Taliban stands for old-school Pashtun tradition more than for Islam. And the Taliban is divided even further, with complicated loyalties to local warlords and tribal chiefs. There are three main factions right now, and the one that runs Kunar Province is run by an old friend of the CIA’s from the 1980s, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Hekmatyar was always a tough guy to handle, for the CIA and the Pakistani intelligence service, ISI, and when the foreign troops finally withdraw, it’s a safe bet that his faction of the Taliban will just switch to fighting the other two. But for now, the three factions seem pretty solidly united against the ISAF, the American-dominated occupying force.

When the U.S. Air Force started bombing Afghanistan in October 2001, the Taliban had beaten the Uzbek/Tajik Northern Alliance and controlled most of the country. Not all of it; the Taliban never had the strength to control all of Afghanistan. In fact, it was overstretched, with small garrisons scattered through hostile tribes’ territory. The Taliban had also managed to make itself hated by just about all the non-Pashtun population of the country by pushing its backwoods Pashtun rules on everyone else, and shooting or hanging anybody who complained.

What’s scary now, for the ISAF’s chances of holding on to the country, is that the Taliban seems to have learned its lesson. It never had a reputation for sophistication, and its hillbilly Pashtun ways weren’t exactly calculated to win hearts and minds. The Pashtun have always been a little strange. They have probably the most anti-women attitude of any tribe on earth. Here are a couple of Pushtun proverbs that give you the general idea: “Women belong either in the house or in the grave,” and “Even one’s own mother and sister are disgusting.” They don’t even claim to find women attractive; for the typical Pashtun warrior, the sexiest thing around is a little boy.

But, like the old saying goes, “pain is the best teacher,” and the pain the Talibs suffered when they were crushed in 2001-2002 seems to have made them a little more humble and flexible. This is something you see in a lot of guerrilla wars: After a defeat, the guerrillas come back much smarter and more patient, because the enemy has been acting like a sped-up Darwin, pruning the movement by killing off the hotheads, the sadists and the crazies, until only the smarter guerrillas, who had the sense to lie low, are left.

At any rate, the new Taliban has been a lot more patient and sophisticated than the pre-invasion model. So Afghanistan hasn’t been quiet in a good way these past few years; it’s been quiet like the old line in Westerns: “It’s quiet — too quiet.”

The new Taliban has learned to tap into the poor peasants’ grudges. And Lord knows the Afghan peasantry is poor, and getting poorer, with 70 percent unemployment.

Even USA Today, always ready to put a smiley face on total misery, admits that the average yearly income in Afghanistan is only $300.

So overall, Afghanistan has rotten living conditions — not a promising market if you’re selling the new iPhone, but perfect conditions, lab-level perfect, for selling rebellion. In the early stages, successful rural insurgencies don’t even worry about combat much. They focus on quietly setting up a local government that replaces the occupiers’ puppet government. If you’ve read much about how the Viet Cong worked in South Vietnam, you’ll recognize the pattern: The puppet government runs around looking busy in the daytime, but when the sun goes down the guerrillas go into action, collecting taxes and settling local disputes, even holding court proceedings in caves, barns or somebody’s hut. The idea is to keep the locals from contacting the occupiers, denying them basic intelligence about what’s going on in the villages, and at the same time making your group indispensable by helping to handle the local feuds, even helping them in the fields. The Taliban has spent the last six years doing all that, to the point that most of Afghanistan now has Sharia-based Taliban courts settling criminal cases.

Against this sort of insurgency, the only effective countermeasure is good, sophisticated local intelligence. And we haven’t exactly won any prizes in that department, in Iraq or Afghanistan. If you’ll recall, the first American casualty was a CIA interrogator named Johnny Spann, who got mobbed by Taliban prisoners he was trying to interrogate at Mazar-i-Sharif. Spann was the first to interrogate the infamous John Walker Lindh, our own Marin County-raised Talib, and what he asked Lindh — up there in northern Afghanistan, in a crowd of flat-hatted, sullen Talibs who were just about to rush him — was, “Are you a member of the IRA?” (I wish I knew what Lindh said back, in that Marin County stoner drawl: “Nooo, deewd, but I was in the Tamalpais High Jazz Band.”)

To make up for the big gaping hole where our military intelligence should be, we’ve been using William Westmoreland’s failed formula: massive firepower. Donald Rumsfeld’s doctrine of doing counterinsurgency warfare on the cheap, with very few troops and lots of air strikes, means that the ISAF has very little local intelligence and has to depend on air power, which worked well enough in the initial defeat of the Taliban in 2002, but just plain doesn’t work in counterinsurgency warfare, because that kind of warfare is about not firing until you know exactly who you’re shooting at. To gain that sort of local knowledge, you need troops settling in to the villages, getting to know people. What you don’t need is F-18s orbiting at medium altitude looking for targets. Unfortunately, that’s what we’ve been using to suppress the Taliban.

Those fighter jets can’t tell the difference between a wedding party carrying the bride to her husband’s village and a Taliban column moving to the attack. And when in doubt, they tend to assume all large groups on the move are Taliban. For six years, ISAF warplanes have been bombing Pashtun wedding parties and processions. It seems to happen over and over again. I’m not sure why. Maybe weddings are the only time that Pashtuns get together in big numbers, big enough to draw fighter pilots’ attention. Maybe it’s their habit of firing rifles to celebrate. But for whatever reason, we have bombed and strafed enough wedding parties to rouse centuries of hatred from the Pashtuns.

And it’s no coincidence that one of the worst of these wedding attacks happened a few miles from Wanat, exactly one week before the Taliban attacked there. On July 7, U.S. Air Force planes killed 47 civilians in a wedding party in Nangarhar. Apparently they mistook a column of relatives taking the bride to her new village for a Taliban force on the march.

That’s the kind of mistake that makes guerrillas very happy. If you’re a Taliban commander, you couldn’t wish for a better scenario than a U.S. air strike on a wedding party to rile the people up against the foreign occupier. The guerrillas don’t lose a single fighter in an operation like that. In fact, they gain huge numbers of recruits because everyone who hears about the air strike wants to volunteer to avenge the dead. By trying to do Afghanistan on the cheap, following the Rumsfeld Doctrine that air power can do everything, we’ve played right into the hands of the new and improved Taliban.

This article first appeared on Alternet.org.

Read more: afghanistan, guerilla warfare, taliban, the war nerd, wanat, war, Gary Brecher, The War Nerd

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

Trackback this post