Now that I’m back in print, I’m starting to hear it all over again: Ames, are you some kind of anti-Russian?

The short answer is, if I didn’t like it here, I’d leave. The long answer goes something like this: You have no idea what my life was like before I arrived. So I’ll tell you.

In late 1991, after a trip to Leningrad, I returned home to California. Almost immediately, I moved in with my Czech emigre girlfriend, her mother, and three boarders in their care home in Foster City, California, a bland middle-class suburb built on a landfill site over the San Francisco Bay. A “care home” is a kinder, cheaper version of a “nursing home” (the nursing home being the elderly’s final pit stop before the ironically named “funeral home”). In California, we’ve created an effective four-step death-by-old-age program: home; care home; nursing home; funeral home. I was living in the second circle. Concurrently, I contracted a horrible skin rash that had doctors from San Francisco to Boston scratching their heads-while I scratched my ass till it bled white.

Our cast of care home characters was so grotesque that even I didn’t find it funny. One of the boarders, Doris, suffered from acute panic attack syndrome. She’d wake up in the evenings tapping on our bedroom door, begging for us to call an ambulance. We couldn’t pump enough tranqs into her mouth, hard as we tried. One night, my girlfriend’s mother slapped Doris in the face to shut her up. It led to a raid by well-meaning California State social workers-our smiley-faced version of the Gestapo.

Another boarder, Helen, was officially insane, and suffered from some kind of semi-emphysema. When she coughed, you felt it in your stomach: it sounded like bits of glass were rattling in her lungs. The third boarder, Joanne, was a sweetheart. I really loved her. She used to sit on a chair with the black telephone on her lap, waiting for someone from her family to call. They rarely did. She lost her dentures once-she called them her “dining set”-it took us a week to fish them out from behind Doris’ bed.

When the social workers raided the care home and closed us down, Joanne was shipped, against her will (the happy-faced California social workers told Joanne that it was in her interests), to a Taiwanese-run care home in a neighboring suburb. Joanne was confused. She broke her hip less than a month later, and died about eight months after that.

Now I ask you: Spend a few months inside this reality, this care home located at 214 Sand Piper Court, in Foster City, and tell me about California Dreamin’. Then step outside for a stroll along the sunny suburban streets, with its semi-manicured lawns, cute woodsy mailboxes, sparkling minivans in the driveways… sometimes you see a neighbor in his 49ers T-shirt and shorts, but he never acknowledges you, and you don’t dare say a thing to him.

Ahhh, the California suburbs: so hot on the outside, so cold to the touch.

Only one thing, one hope or dream, kept me going. Russia. I’d visited Leningrad in 1991, and it was so… unaffected, so raw, so crowded with exceptions. Leningrad was the inverse, the complete negation of suburban California. It was cold on the outside, and warm to the touch, exactly my dimensions.

So I sat in that Foster City care home, popping Seldanes by the dozens, anything to relieve the itch. I spent my afternoons reading and re-reading Russian novels in translation, trying to transport myself, Star Trek-like, back to the cold Baltic winds of Leningrad, to the punks I’d hung out with: Igor and Vanya, Tanya the hooker, Olga the television factory worker, Andrei the metalhead, Sasha the poet-junkie, Dasha who fed me steak while I was stoned out of my mind… I read and scratched, scratched and read: Gogol, Dostoevsky, Limonov, Platonov, khrrrrsh! khrrrsh! khrrrrsh!

I didn’t know how to physically get back to Russia. I didn’t know how to do it. So I took a half-way measure, a kind of care-home decision. In late Ô92, my girlfriend and I moved to Prague. Big fucking mistake. Prague: the care home of Central Europe. In many ways, Prague was worse than Foster City: the fake urban setting, the fake mysteriousness, the fake Czech extras mingling with the thousands of American suburbanites, dressed up for a fake Tom Waits concert in their poetry-slam uniforms and lip hoops and tattoos. Prague plied you along with its Kafka props-it made you feel that you were experiencing something interesting, but it was dead underneath, bland and dead.

Then, in early 1993, my stepfather got brain cancer. Glioblastoma-the most aggressive of the four types of brain tumors. It was a good enough excuse to abandon Prague. My stepfather and I made a deal: I’d help him, and he’d find me a way (i.e.: a visa) into Russia. It worked. I moved back to the suburbs, and nursed him to his agonizing, abandoned-by-all-his-California-friends death. On the day that he slipped into his coma, I called Delta Airlines. After I booked my flight to Moscow, the nursing home ambulance people arrived to take my stepfather away. I watched them carry his naked, comatose body, still heaving, down our wooden steps, past the potted pansies, past the jasmine-and-juniper-lined driveway, then slowly pass by the neighbors down the road, the very neighbors whom we’d never spoken to, who peered discreetly from out of their kitchen window… It was a boiling hot day even by Santa Clara Valley standards, almost a hundred degrees, with a second degree smog alert.

I arrived in Moscow on September 9, 1993, and have never thought of moving back. What I have come to realize is that in fact, suburban California is the negation of Russia, and not the other way around. Of course it is. California’s newer, brand new-like some evil Proctor & Gamble marketing product; everything new is a negation of the old. I now live in the positive dimension. I was right to abandon California. Even if the world is warming up, I’ll stay here, where it’s cold.

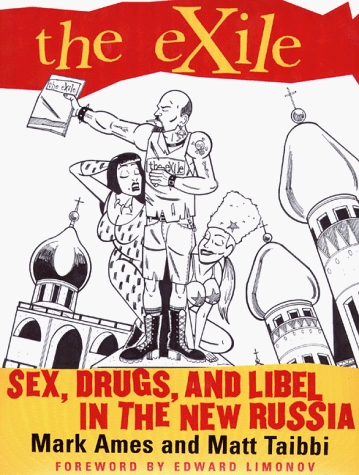

This article was published in Issue #2 of The eXile in March 1997.

Read more: exile issue 2, moscow babylon, Mark Ames, eXile Classic

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed