This summer I traveled to Quanah, the dusty North Texas railroad town that Harry Koch called home, to find out more about the life of the man who spawned the two most powerful oligarchs of our time…

A version of this article was first published in The Texas Observer…

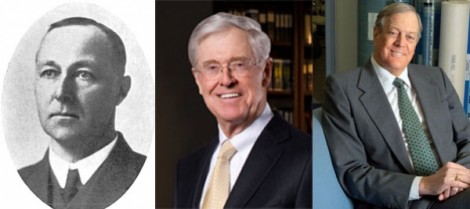

CHARLES AND DAVID KOCH are the most powerful right-wing billionaires of our time. They have spent hundreds of millions bankrolling a broad attack against Social Security, organized labor, financial regulations, environmental protection and public education. The brothers plan to funnel at least $200 million to elect right-wing, anti-government Republicans in 2012, according to Politico. They seem hell-bent on dragging America back to the dark days of unregulated capitalism. The history of their grandfather in Texas may help explain why. Because, apparently, it runs in the family.

Little has been written about Harry Koch. He’s the least-known member of the Koch family. What has not been reported is that the Koch family has been marching under the same laissez-faire banner for the past three generations, ever since Harry emigrated to America in 1888, settled in a North Texas railroad town and became an aggressive newspaper publisher and booster. He shamelessly shilled for railroad and banking interests, amassing his wealth by helping big business fight organized labor and squelch reforms.

Much of the Koch brothers’ ideology can be found in Harry Koch’s newspaper editorials of nearly a century ago. Take, for instance, the Kochs’ current fight against Social Security. Harry Koch took part in a multi-year right-wing propaganda campaign to shoot down New Deal programs. Grandfather and grandsons employ eerily familiar talking points to bash government pension and welfare programs.

“No political system can possibly guarantee either a national economic security or an individual standard of living. Government can guarantee no man a job or a livelihood,” Harry Koch wrote on February 1, 1935, nine months before Charles Koch was born.

Fast-forward 75 years and you can see Charles Koch using the same lines of attack in his company’s newsletter: “government actions … stifle economic growth and job creation, which in turn will significantly reduce the standard of living of American families.”

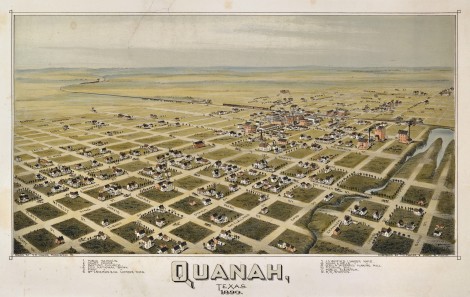

This summer I traveled to Quanah, the dusty North Texas railroad town that Harry Koch called home, to find out more about the life of the man who spawned the two most powerful oligarchs of our time. After spending days hunkered over newspaper archives and rifling through a century’s worth of county records in the town’s tiny courthouse, I began to see a picture emerge of a man who spent his life learning how to use newspapers and media for ideological manipulation and as a platform for pro-business agendas. As I strained to read the battered microfilm, I was constantly surprised at the degree to which Harry’s views—on everything from the economy to the role of government in a democratic society—have been passed on nearly unchanged through two generations, and are now being pushed by Charles and David Koch.

HARRY KOCH WAS BORN in Holland in 1867 to a wealthy German-Dutch family of merchants, farmers and doctors. After apprenticing to a newspaper publisher, he decided to seek his fortune in America. At 21, he set off on a steamer and arrived in New York on Dec. 5, 1888. He spent his first few years in America working for various Dutch newspapers in Chicago, New Orleans, Grand Rapids and Austin until, in 1891, he finally settled down in Quanah, a town that the railroad had established just a few years before. Harry always remained curiously vague and evasive about why he decided to stake his claim in a remote North Texas town, but there is no real mystery to it: he came because of the railroads.

In the second half of the 19th century, America was in the grip of a massive railroad boom. Boosted by eager investors, lucrative subsidies and free land, railroads sprung up connecting every corner of the United States without much thought for demand or necessity. America’s rail mileage quadrupled from 1870 to 1900, with enough track laid down by the end of the century to stretch from New York to San Francisco 66 times.

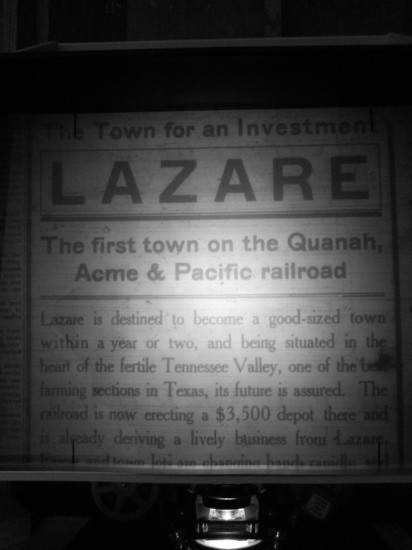

In those wild early days of the railroad age, real estate speculation was a central plank of the business plan. The U.S. government had given vast stretches of public land to railroad companies, and the companies needed to sell that land to settlers to create customers and pay off debts. And that meant railroads were in constant need of local publishers to promote the countless railroad towns that had been planned and parceled by the railroad companies across the country, with the aim of luring enough gullible settlers with wildly exaggerated stories of fertile soil and prosperity to trigger real estate booms—all so that railroad insiders could make easy money offloading overpriced dirt lots on the hapless settlers.

Dutch investors were heavily involved in several railroad lines in the North Texas area, including the Fort Worth and Denver Railway Company, which had spawned Quanah in 1887 and owned just about all the land in town. County records show Harry provided advertising services and worked directly for the Fort Worth and Denver for nearly 20 years, sometimes receiving payment in the form of land transferred directly from the legendary railroad builder Grenville M. Dodge, who helped lay the Union Pacific and more than a dozen other lines across the country.

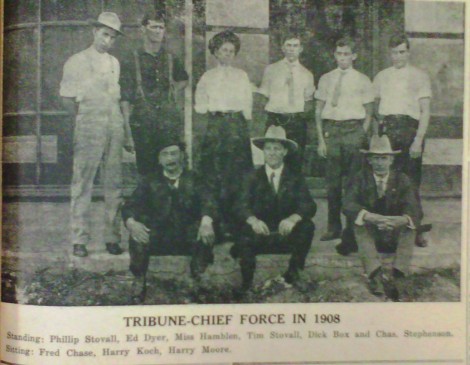

Harry bought up two of the town’s newspapers, apparently with his own money, merged them into the Quanah Tribune-Chief, and began printing beguiling stories of Western prosperity.

When Harry moved to Quanah, it was little more than a dusty settlement with a patchwork of dirt lots, a few rudimentary buildings and a railroad platform—a get-rich-quick scheme laid out on paper. It was his job to create the demand, bring people in and make the town a reality. He ran his paper like a chamber of commerce newsletter, cramming it full of stories about growth, expansion and the limitless possibilities of life on the frontier. He helped inflate a real estate bubble that, along with the presence of the railroad, nearly quadrupled the county’s population to more than 11,000.

Harry Koch worked hard to bring a number of railroad spurs to Quanah, and helped make it a major transportation hub by the early 1900s. He acquired stakes in local businesses, got into the oil business and boosted for notorious railroad barons like Jay Gould. As the town grew, so did Harry’s fortune. He amassed substantial real estate holdings in and around Quanah, which allowed him to cash in on the real estate boom he had helped to create.

Harry enjoyed his success. He got married, had two sons, traveled regularly to New York and Europe, and was proud of having crossed the Atlantic nine times. He even described being in Berlin, caught in a huge crowd that had gathered to hear “der Fuhrer” make a speech.

The best way to understand railroads, writes Richard White in Railroaded, “is to regard them not as new businesses devoted to the efficient sale of transportation but rather as corporate containers for financial manipulation and political networking.” And in that sense Harry Koch was very much of the club.

By the time he retired, Harry Koch was not just a respected newspaper publisher in Texas, but a powerful and highly connected regional business player. He was also extremely well liked. “There is no more popular member of the Association than Harry Koch,” read his bio by the Texas Press Association, where he served as president in 1918.

But the bustling city he helped create was mostly made of hype. Today, Quanah’s population has sunk back to 1890 levels and has little industry left. A gypsum plant on the outskirts of town is the only major employer, and it happens to be owned by the Koch family.

Harry Koch’s rise from immigrant small-town newspaper publisher to entrenched business heavyweight might seem like a classic coming-to-America story, confirming that through hard work, perseverance and luck, anything is possible. But that narrative would be misleading. Harry may have lived among settlers who struggled to eke out a living on the frontier, but he was never really one himself. The difference was right there on the surface for everyone to see: While Harry Koch prospered, most everyone else in North Texas descended into poverty.

Towards the end of the 18th century, 100,000 poor white farmers streamed into Texas every year to escape the brutal peonage of the sharecropping system of the South. But despite the stories of success and security spun by railroad companies and boosters like Harry Koch, newcomers found themselves facing a grim reality, and the same monopolistic big money forces conspiring to keep them enslaved in extreme poverty and debt. On top of the crippling boom-and-bust cycles that gripped the country from the 1890s through the late 1920s, settlers low agricultural prices, monopolistic railroad practices, outrageously high interest rates, and inflated real estate prices that made it impossible for new farmers to afford land.

“On the ‘sod-house frontier’ of the West, the human costs were enormous,” writes historian Lawrence Goodwyn in The Populist Moment. “Poverty was a ‘badge of honor which decorated all.’ Men and children ‘habitually’ went barefoot in summer and in winter wore rags wrapped around their feet. A sod house was a home literally constructed out of prairie sod that was cut, sun-dried, and used as a kind of brick.”

The misery and hopelessness of frontier life sparked a powerful new grassroots populist movement, which sought to reform and curb the worst of corporate abuses. Harry Koch was not sympathetic to the cause.

In 1897, while the country was still in the grips of one of the worst economic depressions in its history, Harry Koch penned a long, gushing account of a luxurious trip to a National Editorial Association convention in Galveston, a multi-day affair thrown for boosters and businessmen. Between detailed descriptions of all the oysters eaten and champagne bottles emptied at the swanky parties, he took jabs at organized labor in response to a strike organized by street railway workers on the day of the convention. Koch was furious, calling the strike “disagreeable surprise” that marred an otherwise perfect outing, forcing guests to walk on foot to the next segment of their entertainment. Luckily, disaster was averted when “Santa Fe officials took pity on the suffering newspaper men and made up a train to Woolman’s lake where the oyster roast was to be held,” Koch wrote approvingly.

In a series of early editorials, scoffed at the idea that land rents should be regulated, and ridiculed the plight of heavily indebted farmers, writing that while they might find indebtedness unpleasant, a much bigger problem was their laziness and inability to take care of the farm equipment they had purchased on credit. He patronized Quanah farmers with platitudes about honesty and success: “Be honest. Dishonesty seldom makes one rich, and when it does riches are a curse. There is no such thing as dishonest success.” He delighted in the fact that unlike other cities and towns across America—filled with strikes, riots, political agitation and violent unrest—the people of Quanah largely steered clear of politics, concerning themselves with what they understood best: hard, honest labor. “A very commendable trait among western people,” Harry wrote, “is that they have no time to give to politics.”

To Harry, regular Americans had no place in politics, a domain of capitalists, railroad men and progressive boosters like himself. Democracy itself was an abomination, a dangerous idea that needed to be constrained and restricted to the upper classes of society. In fact, he considered laws to be overrated. “If we depended upon laws to make us perfect the United States should be a near Utopia and Texas would be the most heavenly spot on earth,” he editorialized.

THROUGHOUT THE 1890S, Harry never shied from using his newspaper to promote specific business interests, and as a platform to express his aristocratic views on society.

But something began to change at the turn of the century. Koch shed his abrasive attitude toward the masses and began reinventing himself as a champion of the common man.

In 1901, Koch published a long editorial that hinted at this transformation. In the piece, he defends popularly embattled trusts and monopolies with the counterintuitive argument that such protectors of wealth were a force for the common good. He based his argument on the false notion that trusts lowered the price of consumer goods:

“Let this thing be borne in mind as significant, that all real trusts, all that are destined to succeed and endure, are established on a basis of permanent lower prices for their products. Everybody knows that sugar and oil have been considerably cheaper since these industries have been under trust control. And the same is true, barring periods of fluctuation, of all industries under effective monopoly, from steel rails to cigarettes.”

Harry Koch’s transformation was remarkable: Not only was he attempting to convince readers of his point of view by appealing to their own best interests, but he was fleshing out economic arguments in language that his grandsons continue to use today. Harry’s defense of trusts reads exactly like the pro-monopoly propaganda regularly cranked out by scholars at The Cato Institute—a libertarian think tank founded by Harry’s grandson Charles Koch in 1977. University of California-Irvine Professor Richard McKenzie recently published an article in Cato’s Regulation magazine titled “In Defense of Monopoly,” in which he echoes Harry’s 110-year-old editorial, including this claim: “The monopolist does not charge higher prices; it lowers them.”

This new rhetorical approach was not Harry Koch’s invention. Rather, Harry was being swept up in a larger national revolution in the way American business elites communicated with the public.

At the turn of the 20th century, growing public outrage at the way financial elites were handling the economy, combined with a rapid expansion of voting enfranchisement began posing a real threat to the entrenched interests of corporate power. To protect itself, American business began experimenting with modern public relations techniques and developing strategies to manipulate and manage public perceptions. The goal was to find a way to maintain power in a political system which depended on consent of a largely poor, non-propertied population. With the help of pioneers in modern propaganda techniques like Edward Bernays and Ivy Lee, the ruling class experimented with techniques that allowed it push the same old pro-business, pro-oligarchy agenda in a way that was inline with the democratic aspirations of the day. Bernays, who helped tobacco companies lure women into smoking and primed Guatemala for a CIA coup by creating the appearance of Communist activity in the country, openly talked America’s new, guided democracy and the need to manipulate the public in his 1928 book Propaganda, “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.”

Public relations were a revolutionary development, giving ruling elites a powerful new way of controlling a democratic society without the constant need for brute physical force.

Harry Koch was right in the middle of this transformation.

In 1910, Harry Koch became the founding director, as well as one of the biggest shareholders, of a small North Texas railroad company called the Quanah, Acme & Pacific, rumored to be part of Jay Gould’s vast railroad empire. After two decades of laboring and promoting other people’s railroad interests, he had finally come into his own. The Tribune-Chief became the de facto advertising arm of the QA&P, extolling the region’s bright future and guaranteed prosperity while hawking company shares and promoting land in towns created and owned by the line. He was no longer just a hired PR hand, but a major player at the top of the food-chain with access to lucrative insider perks, including the easy money QA&P made through its pay-to-play practice of soliciting bribes—or “bonuses”—from cities that wanted to be connected to their line.

It is not clear how long Harry Koch remained involved with the QA&P railroad, but one thing is certain: it was a major learning experience. Like every other railroad in the land, the QA&P was always battling unions, government regulations and labor laws, and that gave Harry ample opportunity to experiment with and master Berneys’ newfangled propaganda techniques.

In the early 1920s, a series of railroad strikes that erupted across the country in response to a federally mandated cut in wages were brutally suppressed. In Texas, the governor declared martial law and dispatched State Rangers and the National Guard to break a strike tying up a railroad junction half a day’s ride east of Quanah, and repeated the process in other towns across the state. It was a dark day for unions, which had suffered a stunning and demoralizing defeat on both national and local levels. And when the dust finally settled, Harry Koch moved in for the kill shot to solidify the railroads’ victory.

He didn’t attack unions or insult striking workers. Harry didn’t mention labor disputes at all, but took a more sophisticated approach: He published an item in the Quanah Tribune-Chief promoting QA&P’s decision to award bonuses to some of its employees. The paper said that the company’s generosity made its employees “the most loyal railroad men in the Southwest” and held up QA&P as a model of corporate unselfishness. Not surprisingly, Harry’s PR blurb was picked up by the national trade magazine Railway Age, which praised QA&P and came out in support of paying bonuses to workers, according to The Quanah Route, a history of the QA&P.

The implication of his editorializing was simple enough: railroads are good to their workers; it’s the strikers who are greedy, thankless ingrates. It was a total inversion of reality, and a textbook example of a public relations technique that proved to work wonders—and still does.

There is even a good chance Harry Koch participated in a bit of old-fashioned astroturfing in the 1930s, when a suspicious publication called “QA&P Employee’s Magazine” suddenly sprang into existence. Supposedly created and published independently of management by employees in order to “create a closer relationship among the employees, to make them feel more like one big family and to arouse an enthusiasm for more earnestness and sincerity in our work for the road,” the magazine was a big hit with QA&P brass, who “enthusiastically supported the venture.” One of the magazine’s special Christmas issues was so flattering that it made the QA&P’s president “nearly burst with pride.” The publication was also a big hit with the general business community, generating fan mail from top executives from around the country.

By the end of 1920s, employee magazines were part of the standard propaganda practice in most American corporations, showing just how important perception management had become to the free enterprise system.

But brutal reality kept breaking through the corporate illusion.

IN THE 1930S, corporations were forced to ramp up their pro-business public relations campaigns to deal with the violent backlash in public opinion caused by the Great Depression. “With tens of millions of jobless and hungry, business was initially stunned by the intensity of public hostility,” Alex Carey writes in Taking Risk out of Democracy. “For the first time American business’s ideological hegemony over American society was temporarily broken.” With the free-enterprise system under threat, American business, led by lobby groups like the National Association of Manufacturers, launched a blitzkrieg propaganda campaign that used news articles, editorials, radio speeches, advertising, cartoons and even films. The campaign was “skillfully coordinated so as to blanket every media,” and “it pounds its message home with relentless determination,” according to the president of NAM. The organization still openly talks about this campaign in its publicity material:

“In 1934, concern over many of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal proposals and key labor issues prompted the NAM to launch a public relations campaign “for the dissemination of sound American doctrines to the public.”

Not surprisingly, Harry Koch was right there along with them, rolling out an aggressive multi-year attack against the New Deal at exactly the same time. And while there is no evidence linking Harry Koch to NAM, the Tribune-Chief seemed to hit all the same points: The paper slammed public pensions, regulations, tariffs, unions, muckrakers, labor laws and deficits, and filled its op-ed space with pro-business opinion pieces delivered fresh from New York lobby groups like the American Bankers Association, whose president, R.S. Becht, wrote to assure Quanah readers that there was no need for the government to regulate banks. Industry self-regulation—or “voluntary self reform,” as he called it—would be enough.

Despite, or because of, overwhelming public support for FDR’s pension and welfare programs, they became major targets, with Harry Koch publishing two or three op-eds in a single day attacking them. “Some ten million old folks are wanting to draw $200 a month from the government, and one hundred million stand ready to quit work when they do. Why not pension all of them?” Koch wrote in a February 1935 editorial, while claiming in a different editorial that the “idea of an old age pension is a splendid idea … such a pension is proper. But great care should be taken…in preparing old age pension laws.”

His editorials contained the same familiar right-wing claims that we hear today: that there is not enough money to support “entitlement” programs, that government will tax industry into ruin, that similar programs in other countries have failed, that regulation is unconstitutional and workers, given the opportunity, will quit en masse and live off government charity. And just like modern pundits, Harry Koch didn’t shy away from whipping up racist fervor to turn poor whites against pension legislation, and against their own interests. In 1935, Koch published a bizarre editorial about a rumor that spread “among Quanah’s colored population that the Tribune-Chief contained a request from the government that every man past sixty should report as an applicant for an old age pension” that soon had “every elderly negro in town” cramming into Tribune-Chief‘s offices. It was proof positive that African-Americans, who had been depicted in the paper as “partly civilized” and unable to observe “laws made by and for white people,” were clearly already scheming to tap into the programs.

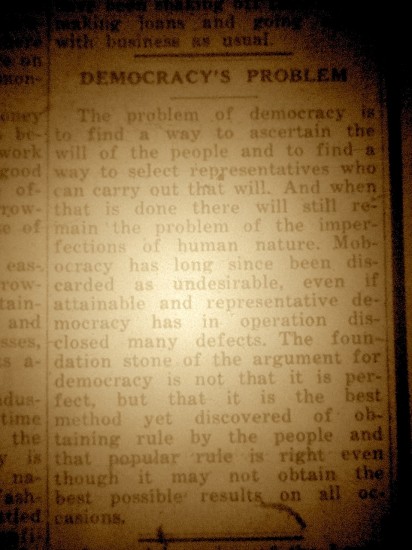

In a 1934 editorial titled “Democracy’s Problem,” Harry rejected “mobocracy,” which had “been discarded as undesirable, even if attainable.” Mobocracy was the right’s popular name for “tyranny of the majority,” and remains a favorite whipping horse of Koch-funded libertarians, who increasingly promote the idea that America is not a democracy and was never intended to be one. Here’s Steve H. Hanke, senior fellow at the Cato Institute, writing in a 2011 editorial: “Contrary to what propaganda has led the public to believe, America’s Founding Fathers were skeptical and anxious about democracy. They were aware of the evils that accompany a tyranny of the majority. The Framers of the Constitution went to great lengths to ensure that the federal government was not based on the will of the majority and was not, therefore, democratic.”

Following NAM’s lead, which had described government programs like social security as the “ultimate socialistic control of life and industry,” the Tribune-Chief kept upping the Communist threat all through the 1930s. He equated all proposals to tax the rich and help the less fortunate with a slippery slope to a Bolshevik takeover of the United States, and joined up with the rest of the country’s pro-business press to smear Democratic Senator Huey Long, a wildly popular freshman from Louisiana and presidential contender who could threaten FDR from the left wing of his own party. Violent editorials constantly appeared in the Tribune-Chief, pegging Long as a covert Bolshevik for his “Share Our Wealth” program, which sought to put a cap on net worth and set up a comprehensive welfare system. After the Senator was shot and killed by a lone assassin in 1935, Koch issued a tacit endorsement of the murder, remarking that it was “not unexpected.”

But the constant fear mongering and red baiting was just another calculated public relations technique, used selectively against political enemies.

What few of his readers knew was that at the same time Harry screamed about the Red Menace, his youngest son, Fredrick C. Koch, was in the Soviet Union working for the Bolsheviks, building refineries, training Communist engineers and laying down the foundation of Soviet oil infrastructure. Fred even hosted a delegation of Soviet planners in his company headquarters in Wichita, Kansas. Fred’s Soviet contract to build 15 refineries personally netted him $500,000, a huge sum of money in the 1930s, but he continued his father’s cynical red menace attack strategy, and took it to a whole new level after he became one of the founders of the far-rightwing John Birch Society, which tried to convince the American people that unions, colored people, Jews, homosexuals, President Kennedy and even Dwight D. Eisenhower were all Soviet agents plotting to overthrow the U.S. through higher taxes and safety net programs.

Harry Koch passed away in 1942, not long after business’ epic battle against the New Deal reforms. The Quanah Tribune-Chief was passed on to his eldest son, who took over the paper with his wife and kept it in the family until the 1970s. Meanwhile, Harry’s other son, Fred Koch, used the fortune he made building refineries for Stalin in the 1930s Soviet Union to ramp up his own business in Wichita, Kansas. He would build a successful oil transportation empire that would one day grow into Koch Industries, the largest private oil company in the country.

But even after the family’s base of operations moved away from Quanah, Harry Koch’s ghost would never be far removed. His life at the intersection of news media, big business, public relations and ideological warfare would be passed on as a family tradition from father to son to grandson, elevating his offspring to ever higher levels of wealth and influence.

This story was first published by The Texas Observer. Check out their great work…and subscribe!

***

Yasha Levine is an editor of The eXiled. You can reach him at levine [at] exiledonline.com. Want to know more? Read Yasha Levine and Mark Ames’ article about the “Koch-Hayek Social Security-Fanboy Letters”:Monster Koch Bust: Charles Koch Used Social Security to Lure Friedrich von Hayek to America.

Read more: charles koch, grandfather, Harry Koch, koch, koch brothers, kochs, Yasha Levine, Investigative Report

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

47 Comments

Add your own1. Trevor | November 7th, 2011 at 5:40 pm

So can we just give Texas back to Mexico already!?

2. jonnym | November 7th, 2011 at 5:59 pm

Great journalism, but it kind of drives one sad, ugly point home for me: In America we’ve been hearing this free-market pro-business bullshit for over a century and yet some of us are *STILL* falling for it. Hopefully, that’s starting to change…

3. I'm Stalin | November 7th, 2011 at 6:22 pm

Problem with that plan, odds are Mexico won’t take the Texans.

4. Punjabi From Karachi | November 7th, 2011 at 9:44 pm

Now this is what I type in the Exile’s name on my address bar for; history, and a new intrepretation of it.

5. Punjabi From Karachi | November 7th, 2011 at 9:46 pm

Why the hell is this piece of shit url not working?!?

And it’s powered by cloudflare! What the fuck are you eXholes uptpo, letting your storied get raped and tossed down the memory hole like this?

6. Punjabi From Karachi | November 7th, 2011 at 9:47 pm

Correction:

What the fuck are you eXholes upto; letting your stories get raped and tossed down the memory hole like this? Oh whoops. It’s back up again.

7. One-eyed Jesus muffin | November 7th, 2011 at 11:24 pm

The outhouse behind the whore house, that’s Quanah.

8. leonard Curren | November 8th, 2011 at 4:52 am

Notice that the kochhead was already from a wealthy euro trash family. self-made my hole. when is this stupid myth ever going to die. (oh wait, the supply of retards is infinite, so never.) Good work Yash.

9. Fissile | November 8th, 2011 at 6:13 am

Excellent and well researched. When you start digging, one thing you learn about American business is that the names and technologies change, but it’s the same old scam over and over. A very good read about financial speculation through out history is Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation. BTW, I have no stake in promoting this book.

10. Robert Dole | November 8th, 2011 at 6:18 am

“He shamelessly shilled for railroad and baking interests…”

Baking?

11. Chester A. Arthritis | November 8th, 2011 at 7:34 am

Has anything good ever come out of Texas, really? Whenever you hear of something bad happening in America, nine times out of ten it happened either in Texas or Florida. We should have saved ourselves the trouble and never stolen it from the Messicans. At least we would have been saved eight years of W.

12. Duarte Guerreiro | November 8th, 2011 at 9:43 am

I think you really missed an opportunity by not naming this piece “Erecting the Koch Clan”.

13. Amy from Texas | November 8th, 2011 at 11:14 am

I just read this article on the Texas Observer’s website. Thank you for bringing us this fantastically researched and detailed article on Harry Koch. It is amazing how so little has changed in over one hundred years. I’ve shared this article on FB and beyond. Great, great job.

14. I'm Stalin | November 8th, 2011 at 11:42 am

@11

Sorry to burst your bubble, but the Bush family is from New England.

George W. Bush was actually born in New Haven Connecticut. His Dad was born in Milton Massachusetts.

Which goes to show you that shit doesn’t know borders, with wealth you can easily transplant yourself anywhere. Of course conservative voters are shit no matter where they reside.

15. Down and Out of Sài Gòn | November 8th, 2011 at 1:30 pm

“Has anything good ever come out of Texas, really?” Lots of great music, actually – from Roy Orbinson to the Butthole Surfers.

Mind you, even the worst shitholes tend to produce good musos. For every Stalin there’s a Shostakovich.

16. wengler | November 8th, 2011 at 3:00 pm

Behind every great American’s story is a great American con.

17. Mike C. | November 8th, 2011 at 6:30 pm

I wonder what TRADE made the DUTCH great grandaddy Koch so rich. But I’m just speculating, and sadly that’s not a crime.

18. Richie Valens | November 9th, 2011 at 12:20 am

So which stadt do you prefer, Yashsa, Quanah or Victorville? Both of them have electricity.

19. Cum | November 9th, 2011 at 6:39 am

Hmm, if I donate will my comments stopped being bl***********DKKRLSDKJLRKLAR)@$*%!? It’s weird that kochwhore posts get through while none of my compliments for the exile authors have gone through! Maybe I should pay something for their genius, rather than being a cheapskate fuckwad.

20. Cum | November 9th, 2011 at 6:41 am

Or they’re not getting sent in to begin with. I blame the browser I’m using!

21. Punjabi From Karachi | November 9th, 2011 at 3:40 pm

Good job boyzes.

22. Punjabi From Karachi | November 9th, 2011 at 3:41 pm

Viva La History.

23. Kristina | November 9th, 2011 at 5:53 pm

Thank you for slaving away in what must have been a cold, dank,poorly-lit library, squinting at God only knows how many pages of blurry microfilm, to research this article. This is why I love the Exile.

24. Chester A. Arthritis | November 9th, 2011 at 10:46 pm

Feeling that I may have unnecessarily dismissed the contributions of the Lone Star state, I will thank West Texas State for giving us more great pro-wrestlers than any other university, namely “The American Dream” Dusty Rhodes, Bruiser Brody, Tully Blanchard, “Million Dollar Man” Ted DiBiase, Stan “the Lariat” Hansen, and Terry and Dory Funk, the only brothers to hold the NWA World Heavyweight Title.

25. artichoke | November 10th, 2011 at 12:13 am

Why do Exile writers pen such longwinded articles? This isn’t the TLS or The Economist.

Please edit your work if you want it to be read, windbags.

26. CB | November 10th, 2011 at 9:34 am

I hate to say it, but as much as I loathe the Koch family and all their works… Last night I saw that they had sponsored Nova on PBS, and I couldn’t help but think slightly better of them.

It’s okay though. I just need to remember that even the biggest assholes did some good in their lives… usually as a pathetic attempt to polish their image for fools like me. Oh well. Fuck them anyway, and Nova still rocks.

27. Mike C. | November 10th, 2011 at 10:57 pm

@CB

You could sponsor Nova if your wallet wasn’t being raped by corporate dickheads. The selectivity of private charity is really just a mockery of their disempowerment of the working class. They’re saying, “Look at me! I get to determine who and what lives or dies! All at my whims! Prove your worth to me! Entertain and adore me!”

28. gren | November 10th, 2011 at 11:06 pm

Occupy the bourgeoisie

29. fuall@fuall.com | November 11th, 2011 at 12:04 pm

YA5HA SUCKS HUGE DONKEY BALLS!!!

WE WANT THE WAR NERD BACK!!!!

30. Trevor | November 11th, 2011 at 1:56 pm

Dear eXiled,

Thank you for allowing people to post URLs in your comments section. Those benders at the Guardian break out the banhammer when I do it. It’s not like I really want to but you know how it is for struggling writers. Ya gotta pimp yourself hard!

31. Burr X | November 11th, 2011 at 4:25 pm

Trevor, Why don’t you go f yourself. Texas defeated Mexico on their own and was their own nation. @11, you never stole Texas from Mexico you moron. Texas was paradise until they starting breeding with the all the yank trash coming to make a quick buck after the civil war. everyone knows that.

32. super390 | November 11th, 2011 at 7:37 pm

@ #26:

Question is, what subjects does Nova avoid to keep Koch happy?

33. super390 | November 11th, 2011 at 7:46 pm

@ #31:

Actual Texas history:

Stephen Austin made a deal with the Mexican government to bring in settlers who would adopt Catholicism and be loyal. Instead, he got overrun by a flood of Tennessee hustlers who always intended to steal Texas and legalize slavery. It was the only way Tennesseeans like my ancestors could get rich enough to own slaves.

So greedy trash was here before the carpetbaggers. And life was hard. The depredations of the rich and the railroads radicalized many Texans in the late 19th century, including Rep. Sam Maverick, who said he believed in private property so much that he wanted everyone to have some.

34. Occupy Decency | November 11th, 2011 at 7:59 pm

OT, but why the fuck does the Exile always allow comments by Down’s Syndrome libertards like myself? to mock ignoramuses and assholes like me and my sponsors? Most Down’s doyyeee doyoyoyee are rather doyeyeyyyee, and do not deserve to have their trolling comments doyeyeyeee please do not hurt my Master. I love the Kochites, liberterians, Wall Streeters, and right-wing media pimps.

If the Exile insists on ridiculing the retarded and corrupt shills for the Kochs, then some day I just may zap them with the Ultimate Troll Comment: Sir, You are morally no better than the Kochites.

Oof, that hurts. Doyyyeeee!!!

35. Trevor | November 12th, 2011 at 6:12 am

“Burr X”? Like the tenth Aaron Burr? And why are you to much of a wimp to just spell out “fuck”? Is it because Texas is full of wimps who needed Grant and the Union Army to bail them out of their stupid pissing match – that they were losing – to Mexico? It’s not like Grant wanted to, he says pretty clearly in his Memoirs America would be better without that ugly scrubland.

36. Peyton Manheim | November 13th, 2011 at 12:52 am

@18: Victor Valley HS Jackrabbits are 1 and 9. The Quanah Indians are 9 and 3. What does that say, dickwad?

37. CensusLouie | November 13th, 2011 at 3:22 pm

@14

You can interpret it as “only places like Texas are dumb enough to elect people like W.”

To be fair to Texas, whenever you hear some horrible quote or bit of legislation that makes you ashamed to be American, 19 times out of 20 it’s from one of the shit hole states like Texas, Arizona, West Virginia, South Carolina, or Kentucky.

Forget letting Mexico keep Texas, the Confederacy should have kept the entire South.

38. super390 | November 14th, 2011 at 7:24 pm

#37:

If the Confederacy had won, the South would now be like Somalia, and no one wants to be next-door to Somalia. Consider that many whites in the Confederacy didn’t accept secession, so their county governments just refused to obey the state governments. Consider that many of the state governments hated each other and viewed their militias as private property. Consider that some slaveowners wanted to invade Mexico and Latin America to capture more slaves. Then combine all that with the impending collapse of the Southern ecosystem, which nearly happened before tobacco was replaced by cotton, and then was postponed by post-Civil War diversification into crops by peanuts (which would not have happened if the South had won since G. W. Carver would have been a slave), only to finally happen for real in the Dust Bowl. The Confederate ideology would have prevented government action to counter erosion.

Feuding tribes, race wars, border wars, regional warlords, and desertification. That’s Somalia.

39. pj | November 19th, 2011 at 5:44 am

Could it be then that all those who tell us right now how hard it is to do business in Russia due to corruption and Putin’s authoritarian rule are in reality making money there just like the Koch family did in their times? What a perfect scam to keep competitors out.

40. Eddie Clark | November 27th, 2011 at 9:18 am

All this talk IS over stolen land: Comancheria, from well before 1400.

41. Tom Dvorak | December 31st, 2011 at 11:30 pm

Yasha, when is your book on the Koch family going to be published?

42. Moshe Goldstein | February 29th, 2012 at 10:22 am

Hey, I was hoping to post an anon anti-Semitic comment here (note my wacky name I put in), wonder what you guys think about this wild brave idea of mine?

43. backwardsevolution | April 18th, 2012 at 2:58 pm

Yasha Levine – writing just does not get any better than this!!!!! Thank you.

44. Peter Hockley | June 8th, 2012 at 8:46 am

“Excellent and well researched. When you start digging, one thing you learn about American business is that the names and technologies change, but it’s the same old scam over and over.” And the same damn families.

45. John Doe | March 19th, 2013 at 6:03 am

Nice piece. The Kochs funded Breitbart and O’Keefe and other character assassins. Can I lick the Kochs’ boots? I sure try to every day

46. Scott Simpson | March 11th, 2015 at 3:53 pm

Fuck the Illuminati Masonic cock sucker brothers.

47. Scott Simpson | March 11th, 2015 at 3:56 pm

Now you have my name you should be concerned.3%

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed