This was first published as a Radio War Nerd subscriber newsletter on May 7, 2022.

NATO’s been around for longer than I have. It survived what should have been its extinction event, the fall of the Soviet Union. In fact, it expanded and became more aggressive once the USSR, its supposed enemy, vanished. NATO’s own site mentions an odd factoid: Its first military operation came, not in the Cold War years, but in 1991.

That’s odd, right? If you’re old enough to remember the Cold War, like me, you took it for granted that defending Europe from the Soviet threat was NATO’s whole purpose, its reason for existing. Western Europe was at the mercy of Soviet tanks, and the NATO forces were the only thing keeping them from rolling in. Thousands of Russian tanks were “poised” — the newspapers always used that word, “poised” — to pour through the Fulda Gap.

Most of us were pretty vague about what the Fulda Gap was and couldn’t have found it on a map — people couldn’t google things in those days, and it was a lot harder to go to the library, grab one of those giant Atlases, and try to find Fulda on it — but we proto-War Nerds were proud of just knowing the term, “Fulda Gap.”

That put us way ahead of the ordinary rubes who uncomplainingly paid their taxes for the expensive weapons NATO stacked up in what was then West Germany, and to show off, we talked a great deal about that Fulda Gap. It was our favorite gap, over there somewhere in the clogged, incomprehensible, history-littered mess of Central Europe. We were very worried about it. It was vulnerable.

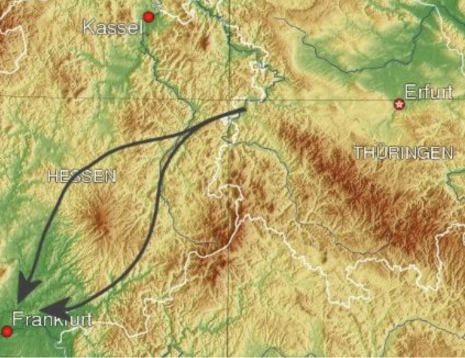

Here’s the actual gap, if you’re interested:

The Fulda Gap, a mythical realm of the NATO Era.

The Fulda Gap, a mythical realm of the NATO Era.

It’s not much, just a route around what passes for mountains over there. But it was vulnerable, that was the key. NATO was always vulnerable, like a silent-film heroine. Those Russian tanks were always on the verge of rolling over NATO like a steam locomotive chugging toward Mary Pickford, tied to the tracks.

But the Russian tanks never came. The rubes still paid for new, more expensive weapons meant to stop them. But they never came. Even when America was distracted, as in the Vietnam War, or during Watergate, they never came.

All through the whole second half of the last century, taxpayers coughed up for endless NATO upgrades and nobody in America questioned or complained about it. I seem to remember the actual Western Europeans complained sometimes, but what did they know? Europe seemed weak, drained of all its fire, gone from berserkers to appeasers in the wake of 1945. Why, those Dutch even let their army have a union!

The US was the bulwark of The Alleged West. And even in Europe, everyone who mattered supported NATO, as far as we knew.

Looking back now, it’s our acceptance of the whole farce that seems odd. You’d think people would catch on after a few decades, but we never did.

It was the old joke, the favorite joke of any protection racketeer: The fact that the tanks never poured through the Fulda Gap just proved how well the protection racket was working.

Any time a nay-sayer dared to suggest that the Russians might not even mean to send their tanks, they got slapped down with the same cliches: “Munich!” “1939!” “Readiness!” and “If you want peace, prepare for war.” That was a big one, that slogan. The less you know, the more sense it makes, and we didn’t know much.

Like I say, this was before the internet — and no matter how annoying the internet can be, you durn kidz just try imagining a world where the censors of the three TV networks and a half-dozen big-city newspapers ruled the entire spectrum of media discussion. Hold your thumb and index finger about a centimeter apart; that was the range of opinion.

And for those editors, it was always 1939. It’s still 1939, for mainstream people. Sure, there have been gigantic, horrific wars all over the world since then, but those wars were in the Global South, the hot countries, and they mostly killed poor, non-European people, who just don’t count for the pundits.

If you think I’m exaggerating, just compare the orgy of commiseration about war in Ukraine with the pundits’ studied silence about Yemen or Tigray. It’s so blatant, so obvious, and so gross that there’s no use even beating them over the head with it. I’ve tried, and it’s like sermonizing your cat. They can’t change, and don’t even want to. They’re comfortable with 1939; it’s the only navigation aid they know, their one lighthouse in a dark world.

Khomeini said, “Every day is Ashura and every land is Karbala.” Well, for a NATO-shilling pundit, and they were legion, every day was the Munich Conference, every dissent was “appeasement,” and the only danger was not pouring trillions into weapons that would never be used.

And this strange tableau never changed, even as other things were morphing wildly. That’s what amazes me, looking back: the sheer granite stability of the NATO scam. You could call it a tableau vivant, but you’d have to leave off the vivant part. That Russian blitzkrieg never came, but it was always going to come.

Being an American in the Cold War was a lot like belonging to one of those Last Days churches, where you sit through a scary sermon every Sunday about how The Lord is coming soon, very soon, all too soon, and YOU PEOPLE AREN’T READY! YOU WILL BE CONSUMED IN FIRE!

Come to think of it, I wonder if 40 years of believing in those Russian tanks swarming through the Fulda Gap had something to do with the rise of the Evangelicals. They must have found it easy to believe “The End is nigh! You will be consumed in fire!” In fact, that pretty much was the prediction: We would be consumed in fire, but secular, Soviet fire, tank fire.

And all it amounted to was money, the boring, adult stuff Cold-War kids like me never even thought about. Money didn’t seem very interesting in those years. The notion of worshipping billionaires was alien — that’s one thing I have to say, grudgingly, for that accursed era: They didn’t worship billionaires.

But the oligarchs of that era didn’t mind not being worshipped, as long as that sweet Defense money kept coming. Those budgets were as irrational in their details as in their basic premise.

That is to say, they were overwhelmingly invested in conventional, armored warfare tailored to the European battlefield. NATO strategists, and their colleagues (“colleagues” is very much the correct term) in the Warsaw Pact planned endlessly for a replay of the Eastern Front in WW 2.

There was one little flaw in this thinking: Nukes. There were no nukes on the Eastern Front in WW 2. If there had been, they would have been used. Like, instantly. By either side. Used until they were all used up, and Europe was a lake of glass.

So if the Eastern Front sequel, replayed with nukes in the inventory, would inevitably go nuclear, then what was the point of all those troops with rifles, all those tanks?

You’d do just as well — and save a few trillion — by stationing a few thousand unarmed soldiers with radios along the border between East and West Germany. If the Russian tanks crossed the border, the soldier with the radio could call it in, and the ICBMs would fly.

But NATO did not want to think much about that. Nukes were oddly unpopular among post-1945 officer corps. They were a form of automation that the officers’ guild did not favor. They would put all the armored divisions out of business, all the infantry divisions, all the surface navies.

Whereas an updated Eastern Front would mean full employment for the whole guild. And the best part was, you didn’t — you never would, in fact — have to make actual war. You would train endlessly for an event that you and your guild colleagues knew in your secret hearts would never happen.

Because they knew it would go nuclear and nobody wanted that. The big armies in NATO did plan for nuclear war, but glumly, in secret, with none of the zest for publicity they displayed when discussing conventional weapons that could be used against that “sea of tanks” the Russians were always about to send.

Nuclear war was like that line in Ghostbusters:

Bystander, staring up at the sky: “It’s a sign!”

Ghostbusters secretary: “It’s a sign all right, ‘Goin’ out of business!’”

The dream of this perfect, imagined NATO/Warsaw Pact conventional war was so precious that people had to invent scenarios which confronted and defused the nuke problem.

Somehow, the future war had to be conventional. But it had to deal with the existence of nuclear weapons. So storytellers came up with plotlines in which nuclear weapons were used, then abandoned. It had to be mano a mano, with good old tanks, planes and small arms.

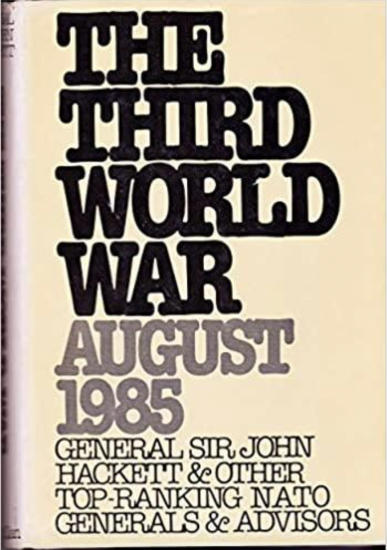

So in the 1980s we got plotlines in which nukes were used only once or a few times, then abandoned in favor of conventional weapons. Sir John Hackett, a “respected” British general, published The Third World War: The Untold Story in 1982.

Hackett clearly savored every battle in his imagined war, except the nuke part. He didn’t look forward to that at all.

So he came up with a storyline that made all his readers happy: Early in the big NATO/WP war, the Soviets nuke a British city, and the Brits respond by nuking a Soviet city. And that’s the end of the nuclear war. After that, both sides stick to good ol’ tank/air warfare.

The genius of Hackett’s plot is the choice of city. It’s a Tale of Two Cities nobody who mattered would miss. So, in his book, the Soviets nuke…Birmingham. Perfect! Nobody Hackett was likely to meet at the MoD or over drinks at the club would miss Birmingham! In fact, they’d wax droll over it, little jokes about how they’d have paid the Russians to take care of Birmingham for them, etc.

And in retaliation, Hackett’s plot has NATO nuking…Minsk. Not to bad-mouth Minsk, but…it’s Minsk, OK? Nobody in the Kremlin would miss Minsk. So, after exchanging pawns, NATO and the Warsaw Pact get down to business, in Hackett’s book, blasting each other with updated WW2 weapons.

There’s something similar in the original Red Dawn (1984), the movie that defined Reagan-era Cold-War dreams.

In the movie, Powers Boothe plays a shot-down F-15 pilot (“I’m an Eagle jockey,” he introduces himself) who parachutes into occupied Colorado and is rescued by the Wolverines, a teen clique of American insurgents. First, Boothe has to justify getting shot down (because Patrick Swayze and his fighters are pretty hardcore, believe you me), which he does by invoking the common view that the Russians had more of everything, including fighter planes. Boothe growls, “There was four of’em. I GOT three!”

After that the Wolverines accept him as an OK fighter and ask him to explain the big war picture to them. Boothe lays it out, his face smeared with expensive “battle-smoke” camouflage, using a stick as they stare into their campfire in the Rockies.

Boothe’s summary has it all, from illegal immigrants who are actually Soviet infiltrators, to a craven Europe which has decided to “sit this one out…all except England, and they won’t last very long.”

Then he adds another commonplace used to explain why the war didn’t go all-out nuclear: “The Russians need to take us in one piece, and that’s why they won’t use nukes, and we won’t either, not on our own soil…the whole thing’s pretty conventional now.”

Every now and then, some troublemaker would break the taboo and ask the old, annoying question, “But wouldn’t an all-out war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact go nuclear?”

That quibble was mostly ignored by the newspapers of record, the television networks, the talk shows. We dreamed of nuclear war, but in an oddly detached way, imagining our cities vanished under the mushroom cloud. It wasn’t a battlefield, and it didn’t have much to do with how we imagined a replay of WW 2 in Europe. It could happen for any reason, our president having a tantrum, the Soviet boss waking up on the wrong side of the bed, anything. We didn’t connect it with trillions spent on NATO, or the 400,000-odd US troops we kept in Europe, along the West Germany vs. East Germany line.

And there was a funny thing about those H-Bomb dreams: They were a feature of the first phase of the Cold War, the 1950s and early 1960s, much more than the second Cold War, under Reagan. Reagan’s Cold War was tilted toward conventional war, while that first phase was dominated by the possibility of a sudden, unpredictable, all-out nuclear exchange.

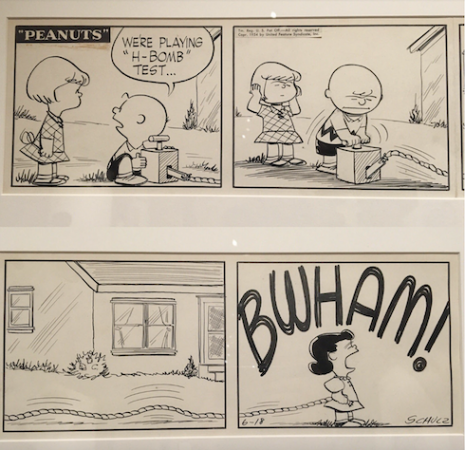

There’s a Peanuts strip, from about a year before I was born, showing how sudden and nuclear people imagined war in the first phase:

Peanuts 1954. This was totally first-phase dreaming, not at all like Reagan-era dreaming.

Peanuts 1954. This was totally first-phase dreaming, not at all like Reagan-era dreaming.

There was a logical problem with US action during this first phase: Everyone thought that the war would be sudden and nuclear, with no role for old-timey soldiers with guns. But at the same time, the US maintained almost half a million soldiers with guns, tanks — the whole outmoded WW 2 arsenal — in Western Europe. So what were they doing, the 400,000 American troops in Europe?

There weren’t enough of them to stop a Soviet blitzkrieg, but there were about 390,000 too many to be pure “tripwire” soldiers. “Tripwire” was a common way to describe them, meaning their job was to get rolled over and call it in.

It’s so strange to remember that now, the “tripwire” talk that pundits used so blandly. That’s something I keep coming back to when I try to remember that dim time, dim in more ways than one: Didn’t they think harder? Didn’t it cross their minds that their strategy was hopelessly confused?

400k soldiers was too many for a tripwire, too few for a deterrent, but we accepted them. I wonder now if that was because we knew it was all theater. I think people did begin to think that, as the years went by with no big war.

Maybe when NATO started in 1949, Americans really expected a big WW3 to flare up in Central Europe, as if the embers of WW2 hadn’t been fully hosed down. But by the 1970s, the idea that the Russians were eternally revving their engines, waiting to hit that Fulda Gap, was a little far-fetched.

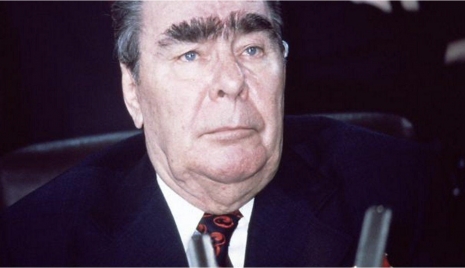

Cool people made fun of army guys (Animal House) and saw “the service” as a last resort of the unemployable. It was not cool at all. Brezhnev was running the USSR, and all it took was one look at his photos to see that this guy’s whole ambition was to die in his bed, as comfortably as possible. He didn’t make a plausible war chief.

Brezhnev: “Just let me die in peace, OK?”

Brezhnev: “Just let me die in peace, OK?”

Only a few specialists thought hard about what those big NATO armies were doing. Most Americans accepted NATO as a form of insurance. You might not need it, but you should always have it, and that means paying the premiums every year.

The premiums were the gigantic Department of Defense budgets Congress voted every year. After all, the way we saw it, NATO really amounted to the United States with a few lesser, much lesser, sidemen. And we made the rules, as shown by the rule about withdrawing:

“…any Party may cease to be a Party one year after its notice of denunciation has been given to the Government of the United States of America, which will inform the Governments of the other Parties of the deposit of each notice of denunciation.

Like a tough landlord, we insisted on a year’s notice. And even when our European allies followed the rules, the U.S. vilified them.

When de Gaulle tried to downscale France’s integration in NATO in 1966 (because he had this quaint notion that France was a sovereign power), he became an enemy forever. I remember the editorial cartoons, the furious opinion pieces, and the scornful reminders of France’s supposedly cowardly record in WW2 after de Gaulle tried to pull France back.

It was obvious, it went without saying, that if NATO showed weakness in any way, those Russian tanks would roll west til they hit the Atlantic Ocean. And maybe they wouldn’t stop there, either. First they take Paris, then they take Manhattan, as Leonard Cohen didn’t say.

De Gaulle’s pride in the French nuclear force may have been odd, by superpower standards. The French (and British) nuclear forces were nothing compared to the Soviet or American stockpiles. In 1977 Britain had 500 nuclear warheads, France about 230, enough to level most major Soviet cities. That seemed small compared to the five-figure totals of America and the USSR.

Those two nuclear forces were something else, unprecedented. The ability to end the planet! There was something hysterical about it, even exciting. I always wondered why no one spoke in favor of nuclear war, but I didn’t say that out loud. You were supposed to be anti-them; even I knew that. Kept it to myself, how beautiful those mushroom clouds were, how right they felt, how deserved.

A still from Akira (1988), in which you get not one but two nuclear annihilations, both beautiful. It’s always fun when 21st c. academics go “Heeeey, there’s jouissance going on with those mushroom clouds!” As my compatriots in Cold-War Pleasant Hill were wont to say, “No shit, Sherlock Ph.D.!”

A still from Akira (1988), in which you get not one but two nuclear annihilations, both beautiful. It’s always fun when 21st c. academics go “Heeeey, there’s jouissance going on with those mushroom clouds!” As my compatriots in Cold-War Pleasant Hill were wont to say, “No shit, Sherlock Ph.D.!”

This made for some awkward conversations with Mark and Steve Shumway, children of a liberal Minnesota family across the street. They would go to their heretical church and get all anxious about nuclear war. It seemed a bit shameful to me, though I tried to be broadminded.

There were lots of jokes about the crazy overkill of those stockpiled nukes, but the people making the jokes were a few fringe comics and lefties, and even they tended to moan about nuclear war as if it was bad weather, something sad that wasn’t anyone’s particular fault. That dog sitting in the flames smiling? Very Cold-War, only the flames were in the future tense. It was an awful lot like thinking about Hell: it would be bad if it happened, but you couldn’t help giggling about it, all those flames.

In fact, a lot of us, I think, felt the pull of oblivion. When I heard Tom Lehrer’s supposedly anti-nuke song, “We’ll All Go Together When We Go,” I heard it as a dream of justice, not a warning.

Every other war killed some people, often the best of their world, and left others, often the worst, alive and gloating. Wasn’t it better, a war where “we’d all go together”

Maybe that was an eccentric reading, but I don’t think, looking back, that I was all that eccentric. Just “outside the permitted discourse,” as they said in grad school. We were legion, the oblivion fans.

There was no real argument in the media about any of this grotesque tableau. In fact, there was very, very little argument in the American media about anything beyond preference for one or the other presidential candidates. I’m telling you, those gatekeepers ruled the world before the internet came along.

The US media lost interest in NATO a bit in the worst years of the Vietnam War, from about 1968-1973. By the time Nixon resigned, the US central government was adrift and the Army was a demoralized branch of the Civil Service.

You had to wonder — well, I had to wonder anyway, in my few lucid moments, why the USSR didn’t attack during Watergate, or in the chaos afterward, when a comically feeble Gerald Ford was fronting the Presidency for the deposed Nixon. The Russians could have won a conventional war easily at that time. They must have known it. Why, I wondered while picking my various scabs, didn’t they send the tanks across that famous Fulda Gap?

That got me wondering why they hadn’t struck after JFK got killed, in November 1963. You wouldn’t believe how that assassination pole-axed America. Hell, even Lou Reed wrote a maudlin song about it. People were paralyzed. And there were constant rumors that the Soviets had killed JFK, either by themselves or via their Cuban proxies.

Looking back, it’s pretty obvious why not. First of all, the Soviets didn’t want to. They were much more afraid of war than America, which had never been invaded. The Soviet elite of that era wanted a little calm, the chance to have a moderately prosperous life. That’s what they’d always wanted: no incursions, leave us alone. No one had taken that World Revolution noise seriously for decades.

Second, they knew what would happen if they did send the tanks across the West German border. The US would nuke every city and military base in the USSR. Of course the USSR would return the favor, nuking every American city and military base, but that wasn’t much comfort.

In other words, only amateurs took those big conventional armies in Europe seriously. What mattered was the nukes. It was that simple.

Which raises the question, what the Hell were those huge, expensive armies all about? Even if you could suspend your disbelief in a purely conventional war, it was impossible to explain how those NATO armies were supposed to survive a long, grinding Eastern Front war. It didn’t seem likely that they could be reinforced from America if an all-out war started.

Even the Nazis had come very close to cutting off trans-Atlantic shipping with no more than a few diesel submarines, and the Soviets were a lot bigger and smarter than the wretched Nazis. The Soviets had magnificent interceptor aircraft (or so we were told) and were always “building” a great navy. How was the US supposed to reinforce its troops in Central Europe across an ocean full of Soviet subs and within range of Soviet interceptors?

There were Popular Mechanix stories that “we” planned to commandeer commercial airliners and use them to ferry G.I.s across the ocean. But even for a trusting Cold War product like me, those stories seemed absurd. They were going to ferry tanks and APCs across the Atlantic, in wartime, on a bunch of re-branded 747s? Those big giant radar-signature planes, in range of the fearsome Soviet fighter-bombers?

Much as I wanted to believe, I couldn’t help thinking, “I don’t think I’d want to be on one of those planes.”

Yet even NATO’s most obvious weaknesses led to bigger budgets because there was always some gadget under development that would fix them. STOL cargo planes would allow NATO to use highways and small airfields, more fighter aircraft would be able protect convoys of cargo planes and so on.

There was always a gadget on the way that would save us. Gadget wars were something we could win, unlike Vietnam, where no gadget, however loudly touted in Popular Mechanix, seemed to make any difference. Russians played war fair, with tanks and planes and a front, a proper front. Them you could beat with gadgets.

And the most feared Russian gadgets were new, secret, superpowered attack planes that could blast those converted 747s out of the sky, like the MiG-25. You would not believe the volume of terrified, awed, enraptured prose about that plane which flowed from the typewriter keyboards of thousands of NATO shills. Hell, Clint Eastwood made a movie about it. That’s how much we all loved to fear it.

The MiG-25, NATO codename “Foxbat” though it turned out to be more of a stripped-down 1970s muscle car.

The MiG-25, NATO codename “Foxbat” though it turned out to be more of a stripped-down 1970s muscle car.

Well, a Russian pilot flew his Foxbat to Japan in 1976, and the techies swarmed over that plane. What they found — though they didn’t publicize it much — was that the MiG-25 was a stripped-down, low-rent muscle car of a fighter. Its famous “Mach-3” speed required a long, slow acceleration; it was hand-welded of nickel-steel alloy, not titanium as claimed; its electronic systems used vacuum tubes, and its range was a crazy-low 300 km/190 mi.

It was essentially a short-range interceptor, useful for attacking bombers or short-range recon, but not much else.

The news that the MiG-25 wasn’t as scary as we’d been told didn’t get out nearly as fast as the claims about its super-powers had. There was no profit in downplaying Soviet threats.

As far back as the “Bomber Gap” and “Missile Gap,” Cold War media told the scare stories loud and clear, but consigned the corrections to page 17. So us rubes had an inflated notion of the USSR’s power, right up until it went out of business.

We had our own champions, like the F-15, marketed as an answer to the “growing” Soviet AF threat.

The F-15 Eagle: Always outnumbered in our dreams

The F-15 Eagle: Always outnumbered in our dreams

It was a good plane (and a very expensive one) but we had so few of them! We always needed more.

There was always that sense that the USSR had more of everything, as in Powers Boothe’s account of his unequal combat against the MiG’s. More tanks, more fighter planes, and more will.

The part about more tanks may have been true, at certain points during the long phony war, but the rest was totally false. The Soviet AF never matched the USAF, and as for the will to fight…well, that myth lasted right up to the moment the USSR fizzled out like a damp campfire. Just plain fizzled out without firing a shot. So much for their iron will, their endlessly growing threat, their terrifying potential.

The collapse of our designated villain was a shock. I mean across the board. A shock to Kremlinologists, a shock to the public, and a giant shock to weapons manufacturers. What’s St George supposed to do when his Dragon ups and dies?

Most of the people reading this will have grown up after that moment, so I should tell you, no one expected it. (Except Andrei Amalrik, and all he got for being right was an early death.)

We had a whole Hogwarts of Kremlinologists, whose job was to read the entrails and practice divination from them. Seriously, there were thousands of these charlatans pulling down tenured salaries in every respectable university in the NATO countries — and not one of them noticed that their subject, their very raisin deter, was about to fold. If they’d been employed by more rigorous institutions — say an actual wizards’ college in some fantasy novel — they’d have paid for their staggering incompetence with a slow and unpleasant death.

They didn’t, of course. They didn’t even get fired. That’s what it was to be part of the NATO industry: You did your part in the charade and got paid for that. Being competent had very little to do with it.

So when the Soviet Union turned off the lights and posted “Closed—Under New Management” in 1990-93, these Kremlinologists did what the Department of Defense and its contractors did: They changed the phrasing of their budget demands and scholarly articles from “Soviet threat” to “Russian threat.”

Thank God the USSR collapsed in the 1990s, because there were word processors by that time, so these people didn’t even have to risk RSI by retyping whole pages. “Soviet” became “Russian,” and they were back in business.

You might be wondering if there was any blushing, any apologies, from the Kremlinologist wizards’ guild. Then again, you might know better. Of course there wasn’t.

Reagan’s administration had so tamed the supposedly unpatriotic and liberal media that they never even called out all the Kremlinologists. I’d see some of them coming out of Barrows Hall, UC Berkeley, home of the Poli Sci Department (and in the running for ugliest building on campus, no small feat at a school which experienced a building boom during the 1960’s). Most were smug wretches like Steven Fish, later famed for trying to smear Stephen Cohen.

And I’d wonder even then, seeing people like Fish striding confidently along in their utter failure, almost with awe, at the mysterious workings of the God of Tenure. I’d think, “God, if all the marine biologists hadn’t noticed that the oceans were about to vanish, they wouldn’t be so smug!”

But the God of Tenure is a Calvinist, and his favors are distributed to many a Holy Willie.

And in a way, being distracted by envy of mere professors was typical of all of us victims of the great Cold War scam. We never even thought about the people who’d been collecting dividends, from Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, McDonell Douglas. That’s where NATO won its victory, in the dividend envelopes that arrived each month — do dividends arrive by month? I don’t really know. Hell, I never even got a tenure check.

All that was left was hazardous industrial waste. Those tanks, “a sea of rusting tanks” as one Soviet general mourned when it was all over; all those planes, whole deserts full of abandoned USAF deluxe models, all just part of the cost of doing business.

And the most bizarre part of NATO’s history, the footnote that was longer than the text itself, was yet to come: NATO’s many, many military operations after its precious Soviet Union had almost ruined things by unilaterally declaring peace.

Gary Brecher is the nom de guerre-nerd of John Dolan. Buy his book The War Nerd Iliad. Hear him read his comic memoir Pleasant Hell in audiobook format.

Subscribe to the Radio War Nerd podcast & newsletter!

Read more: cold war, Fulda Gap, nato, Radio War Nerd, The War Nerd, ussr, Gary Brecher, Radio War Nerd, The War Nerd

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed