In this festive season of the year when cheery death-related imagery like skeletons and ghosts and zombies cluster all around us, it seems fitting that we celebrate someone who really liked death and tried his best to show us how terrific it is: horror film producer Val Lewton.

In his low-budget 1940s films such as Cat People, I Walked With a Zombie, The Leopard Man, The Seventh Victim, and Isle of the Dead, Lewton and his tight-knit creative team generally aligned death with the most beautiful characters, the richest imagery, and the most soothingly lovely camera and editing rhythms. Oh to cast off the harsh noisy nonsense of life and sink into that silent, velvet blackness!

This isn’t mere interpretive guesswork on my part; Lewton was quite literal about it. After watching a screening of the Lewton film The Seventh Victim, an RKO executive said films shouldn’t have “so many messages,” and Lewton retorted furiously, “Well, our film does have a message, and the message is, ‘Death is good!’”

It’s wonderful to imagine the sheer befuddlement on the face of the RKO executive when he heard that one.

The idea of death becoming your best friend makes a lot of sense when you live in America, as Lewton indicated in his earlier films. A Russian émigré transplanted to American soil as a child, Lewton did incredibly well career-wise but never really felt at home in his new country. He remained a brooding but high-functioning outsider all his life.

In his view, Americans are the most death-denying and death-reviling of people, and our tendency toward false upbeat pieties and always “looking on the bright side” flattens us, hollows us out, makes us conformist, cardboard-cut-out figures.

Lewton demonstrates this in stark terms in his triumphant first feature Cat People, centered on a tragic “mixed marriage” between the wonderfully soulful foreigner Irena (Simone Simon) and the “good plain Americano” Oliver (Kent Smith). She’s an artist, a Serbian, a loner, a sufferer tormented by a deadly curse, who wears a singular haunting perfume and lives in a completely individualized apartment full of beautiful objects and images related to her lost homeland, her profession, and her obsessions. There she loves to sit in the dark and listen to the big cats at the local zoo roaring at night.

I covet that apartment!

He works at a shipbuilding business where he measures stuff and hangs around with a gal-pal named Alice (Jane Randolph), who’s as bland and self-satisfied as he is. And—well, that’s about it. If he has a home, we never see it. If has any interior life, we never see that either. When his brief marriage to Irena is going south, he feels bewildered because he’s literally never been unhappy before: “Everything’s always gone swell for me!”

In Cat People you spend a lot of time hunting the dark corners of the image for the “monster.” That was Lewton’s signature move in horror, “fear by suggestion,” letting your imagination go to work on the play of light and shadow and the indications that there’s a great menace lurking somewhere. Irena believes herself to be a descendant of a race of “cat people,” evil creatures that bear the semblance of humanity but if stirred by passionate feelings of desire or jealousy or anger, transform into feline killers. Lots of scenes of Irena communing with the black panther at the zoo, of stalking around in her black-panther-esque fur coat getting more and more beautiful as she embraces her “evil” heritage and her own doom, lots of shadow-play designed to hide a cat-woman on the move.

It was the goal of the Lewton team never to show Irena as the were-cat, so that the audience would be suspended between contrary accounts of what ails Irena, a real cat-woman curse, or a psychological horror of sex. But the RKO brass overruled them and a few cat-shots made it into the finale.

What tends to get ignored about Cat People is the manifest presence of the main monster of the piece, which is Oliver, the “good plain Americano,” standing right there in bright light.

It’s one of Lewton’s favorite moves, to reverse the terms, to destabilize the clichés: if light is traditionally aligned with the safe and known and good, and darkness with the dangerous and unknown and evil, Lewton turns it around and makes light dreadful and darkness comforting. “I like the dark, it’s friendly,” says Irena, and she speaks for Lewton. The dark is also rich and mysterious and the playground of death-friendly things, and the whole world, in Lewton films, seems to become deep and vibrant at night and in shadow.

It’s the old Romanticism vs. Enlightenment wheeze, but it’s a good one, and the Lewton Unit gave it fresh energy in attacking dull American pragmatism.

If the bluff, big-shouldered, 1940s wartime “ordinary Joe” American was widely regarded as a masculine ideal, Lewton refuted it by making several of his representative male protagonists blandly terrible, brainless, heartless, soulless. In Cat People, Oliver first meets Irena when he rebukes her for littering.

An obvious part of his appeal to her is his relative sexlessness—he seems like a big overgrown kid—and therefore he’s less likely to arouse her dangerous passions. There’s never much to choose from when it comes to men in Lewton films; the sexier male in Cat People is a despicable psychiatrist named Dr. Judd (Tom Conway, George Sanders’ brother) who leches after Irena while supposedly trying to cure her, deploying a sonorous upper class toff Brit accent and a small clipped mustache. It’s very gratifying when she puts an end to his combo of phony psychoanalysis and smarmy seduction by killing him.

When Cat People did so surprisingly well at the box-office, for a strange little B-movie that defied classic Hollywood horror film conventions, it allowed the Lewton Unit to continue making films their own way. In I Walked With a Zombie (1943), they cross the light-dark values reversal with black-white racial binaries in a film set in the West Indies, where an unhappy white plantation family whose fortune is rooted in slavery are more monstrous beings than the zombies, or the zombie-makers rooted in the indigenous black voodoo culture.

The most celebrated sequence in the film features the hired nurse Betsy (Frances Dee) taking the seemingly zombified white wife of the plantation owner to the voodoo temple for a possible cure. As they slip away from the plantation house, which is ablaze with light but full of miserable bastards who are no use to anyone including themselves, they pass into the cane-fields for a night walk of such beauty it seems like the most marvelous fate of all to lead a zombie through a shadowy “valley of death” marked by talismanic gourds and skulls and carcasses, there to meet another, greater zombie, the “god of the crossroads,” standing at the border between life and death, and black and white cultures.

You guess which side Lewton is on!

(Though he’s not simplistic about it—Lewton won’t let you rest easy anywhere. Once they get to the voodoo temple where the magnificent black-clad voodoo priest does a sword-dance–finally, a worthy male in a Lewton movie!–it’s revealed that the mother of the plantation owner, a kindly-seeming white woman who provides medical care to the locals, has infiltrated the voodoo power hierarchy and practices out of the temple. Her reason? In order to get “these people” to obey her.)

And so they went on, the Lewton Unit gang, elevating death and darkness right there in plain sight for a few glorious years. There’s a lot of heartening crossover between Lewton films and film noir, which was on the rise at exactly the same time in the early 1940s.

In The Seventh Victim, by far the most gorgeous and worthy individual is the enigmatic and quietly suicidal one, Jacqueline, who wears a black fur coat and a stark black wig, and keeps a rented room with nothing in it but a noose and a chair under it, always at the ready.

In her quest for some sort of rich experience, she’s wound up entangled with Satanists. They’ve turned out to be another boring bunch of middle-brows who have card parties and exchange epigrams—Dr. Judd, back again, is a popular favorite in one party scene—and your heart goes out to Jacqueline, because it’s so often the way with supposedly daring degenerate types bragging about sin on a grand scale. They’re generally the dullest of the lot.

And then in Curse of the Cat People, a sort-of sequel to Cat People, dismal Oliver and Alice are back, as parents this time, so you can picture the struggles of their poor kid who actually has an imagination. This kid, named Amy, comes up with an imaginary friend, who’s maybe also the ghost of Irena, Oliver’s dead first wife. She’s apparently the only interesting person these people have ever known. Lewton wanted to call the movie Amy and Her Friend, an oddly drab title till you think about how, for Lewton, Death is the ultimate friend.

When Lewton himself died, of heart failure at age 46, he looked 66. There’s a good argument to be made that he literally killed himself with work. He made nine Lewton Unit films in four years, working on low budgets and tight schedules, doing physical production by day and script-writing by night. It’s rare that a producer gets the coveted “auteur” label generally reserved for directors, but in Lewton’s case there’s vast evidence of his creative control over most aspects of his films. He was a man on a mission. He wanted to counter a terrible American tendency to deny death that only a few others ever seemed to notice—which is odd, considering America was fighting a world war at the time.

Brilliant critic Robert Warshow, one of the rare noticers, says in his 1948 essay “The Gangster as Tragic Hero,” that for Americans, “failure is a kind of death”—and conversely, death is a kind of failure. Therefore we want no truck with either, though this makes us lonely and desperate and willfully obtuse, and deforms all our lives. In Isle of the Dead, Lewton and company make this argument as explicitly as they can, by dramatizing the hopeless attempts to stave off death from the plague, or the vorvolaka (kind of a Greek werewolf-vampire hybrid), through rational, pragmatic means involving obsessive hand-washing and paranoia and isolation from each other and no touching and certainly no sex. As characters die off one by one regardless, the wised-up survivors finally get it: better to “make friends with death,” and as a result live fully while you can.

I recommend you watch a few Val Lewton films this Halloween and get in the proper spirit of the season.

Read more: Cat People, Curse of the Cat People, Halloween, horror, I Walked With a Zombie, Isle of the Dead, The Leopard Man, The Seventh Victim, Val Lewton films, Eileen Jones, movies

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

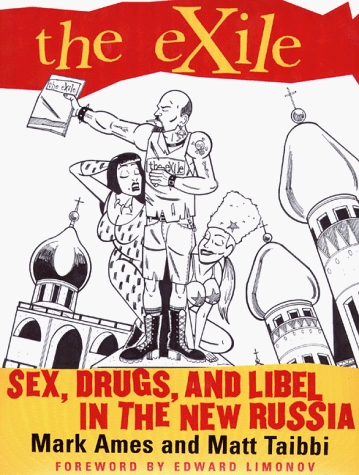

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

20 Comments

Add your own1. Sly Cooder | October 29th, 2012 at 5:42 am

Pretty inspiring read, I just may do that.

2. Joys of Dawn | October 29th, 2012 at 6:23 am

Eileen, you’re cool but somebody who writes about death as lovingly as you has one heck of a suicidal streak

3. Jackie Magoon | October 29th, 2012 at 6:34 am

Ahhh, you’re swell Eileen, just swell.

4. DSCH | October 29th, 2012 at 8:34 am

Great, Wagnerian bullshit. Artists are martyrs! Everyone else doesn’t deserve to breathe!

5. LIExpressway | October 29th, 2012 at 11:17 am

Great reviews Eileen. I have always wanted to see the well regarded Cat People, and now I will. You seem to be familiar with the writings if Ernest Becker(The Denial Of Death) and Sheldon Solomon’s work regarding terror management theory.

6. The Gubbler | October 29th, 2012 at 12:26 pm

Imitation Of Life (1959) final scenes

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3B36_sybpws&feature=relmfu

7. The Gubbler | October 29th, 2012 at 12:46 pm

“Gloomy Sunday” performed by Pauline Byrne w/Artie Shaw and his orchestra

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BYSWdJ0UgH0

8. The Gubbler | October 29th, 2012 at 12:49 pm

Vera Lynn sings “We’ll Meet Again”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gb0mxcpPOU

9. aleck | October 29th, 2012 at 7:47 pm

Surrender your tumblr account, she-devil!I know you got that photo by it! You cant lurk from my evil light for long, now that I know you have one

skREEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE

10. franc black | October 29th, 2012 at 10:06 pm

Wow, Eileen ! You’re back. This is the stuff that gets you noticed.

11. rick | October 29th, 2012 at 10:08 pm

Eileen Jones is notably good, but this site just isn’t fun anymore, otherwise. With the loss of the War Nerd and stylistic changes, you’re talking about sex, drugs and violence almost totally excised from the DNA of the publication. What the fuck, honestly? “Let’s get rid of the sex, drugs and violence?” Maybe you were in Russia too long, since this is not American showbiz. I like human corruption and weakness in the face of greed and degenerate forces, but even there you’re a bit too partisan and political, now.

12. Ain't nobody just like this | October 30th, 2012 at 1:18 am

@11

the overall American schema does seem to be sliding away from fun and towards authoritarianism and puritanism

don’t worry, though; all we have to do is choose the right authoritarians and puritans and we’ll be fine

I mean, I won’t be, but

13. gc | October 30th, 2012 at 2:51 pm

@11

Meaning: “I’m a libertarian and I can’t pretend the Exile(d) thinks I’m cool any more.”

14. skullsneedtobecrushed | October 30th, 2012 at 8:23 pm

@6 — those final scenes would’ve been much better and subtler if the daughter’d been hurled into a pit of chainsaws.

15. The Gubbler | October 30th, 2012 at 10:45 pm

@14 – I suppose it wasn’t really in the spirit of the Halloween season, but it had clear eyes and full heart (and Mahalia Jackson).

Speaking of seasons,

FUCK YOU OHIO!!!

Kill them, kill them all!!!

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to go change my magic underwear and hire 200,000 math and science teachers so America can compete in the global economy.

16. The Gubbler | October 30th, 2012 at 10:54 pm

@14 – It just occurred to me, there was scary eyebrow pencil, so maybe it was appropriate after all.

I can’t think of anything else to say right now.

17. Adam | November 1st, 2012 at 8:25 am

Eileen, thank you for making this Halloween a little more thoughtful and a little less kitsch.

As you said, what’s horrifying about Cat People is having to stare the vacuousness of the chipper, up-beat American right in the face, and, most disturbingly, to know it’s part of you.

18. MCSquared | November 4th, 2012 at 9:40 am

I took your advice and watched “I Walked with a Zombie” last night. I would argue for Paul, the malignantly depressed oldest son, as the chief monster in the movie and the alcoholic youngest son as the closest thing to a hero. Even the mother’s well-meaning cruelty was carried out in a futile attempt to make Paul happy, so I think Paul was the nexus of evil in the movie.

19. Ass for Gas | November 7th, 2012 at 2:48 pm

Ugh. Jesus, Eileen could you get any more Maudlin? Hope you snap out of your depression soon — chin up kid!

20. John Blacksad | December 12th, 2012 at 6:16 am

DSCH did not understand a fuck but nonetheless ranted about it.

For sure, he doesn’t deserve to breathe xD

This is not a Wagnerian bullshit or artist martyr issue,

this is about the north-american tendency

to deny and revile death

and to despise the outsiders who don’t always “look at the bright side”.

A tendency well depicted by people like you, I must add

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed