Robert Creeley: Great Poet or One-Eyed Interspecies Plagiarist?

Here are two pieces of twentieth-century verse. One has been called “…the most often quoted, even the most widely known, short poem” of the 1960s; the other is from a long-forgotten collection of comic newspaper verse. One was written in 1954, the other almost four decades earlier.

Exhibit A

…the lamb frolicked

about her new found friend

gambolling as to the sound

of a wordsworthian tabor

and leaping for joy

as if propelled by a stanza

from william blake…

gently he cut her throat

all the while inveigling

against the inhuman wolf

and tenderly he cooked her

and lovingly he sauced her

and meltingly he ate her

and piously he said a grace

thanking his gods

for their bountiful gifts to him

and after dinner

he sat with his pipe

before the fire meditating

on the brutality of wolves

and the injustice of

the universe

which allows them to harry

poor innocent lambs

and wondering if he

had not better

write to the paper

for as he said

for god s sake can t

something be done about

it

Exhibit B

As I sd to my

friend, because I am

always talking, — John, Isd, which was not his

name, the darkness sur-

rounds us, whatcan we do against

it, or else, shall we &

why not, buy a goddamn big car,drive, he sd, for

christ’s sake, look

out where yr going.

Exhibit A is an excerpt from “Aesop revised by archy,” published in the New York Daily Mirror during the First World War.

Exhibit B is Robert Creeley’s “I Know A Man,” written in 1954, which has been called “…the most often quoted, even the most widely known, short poem” of the Sixties.

Creeley is still considered a great poet, and “I Know A Man” is still his best-known poem. Don Marquis, author of Exhibit A, wrote his poem as a quick way to fill his daily newspaper column. After grinding out columns six days a week, he left journalism in 1923 and died wretchedly during the depression.

Odd, isn’t it? Reading them together, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the great Robert Creeley stole his whole schick from an insect. Because “archy,” the narrator of “Aesop revised by archy,” is a cockroach.

Look at the last three lines of the two exhibits. In the conclusion of Exhibit A, Marquis, writing more than thirty years before Creeley, demonstrates every technique that supposedly made Creeley such an original poet. The desperation is there: “for god s sake” as is the stuttering, awkward line breaks: “…can t/something be done about/it”—each time, the line ends where it shouldn’t, in the middle of a phrase. The last line is the single two-letter word, “it,” unpunctuated, leaving the hypocrite protagonist’s rhetorical question hanging, its presentation as ugly as its moral basis.

Creeley’s Exhibit B shamelessly trots out all the same techniques, like 1977 punk rock duds on a 1990s catwalk. There’s the unpunctuated desperation: “drive, he sd,”; the intentionally stumbling line breaks: “…for/…look/out…” the shorthanded, compressed delivery (“sd”).

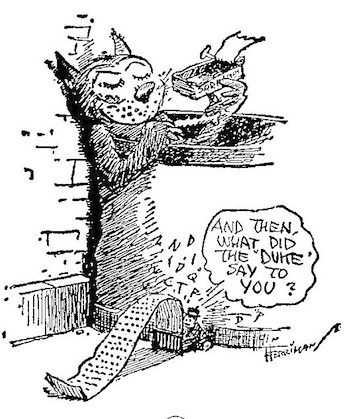

Creeley got famous and adored for his theft. But his poem isn’t just derivative of Marquis’s, it’s simply not nearly as good. It lacks the whole brilliant backstory of Marquis’s Exhibit A. Marquis introduced “archy” to readers of his column as a cockroach, the transmigrated soul of a “vers libre” poet who was karmically punished for practicing “the artless art” of free verse by being demoted to vermin status. He makes a deal with Marquis, whom he addresses in his poems as “boss”: if Marquis will supply him with some scraps each day, especially bread, which he misses intensely, and set up the typewriter, he’ll write his adventures as a cockroach each night.

True poetry: archy and the cat mehitabel.

Of course archy can’t manage punctuation, capitals, or other typographical frills, because the only way he can work the typewriter is by jumping down on a key, and those things require hitting two keys at once. So Marquis not only parodied the Prohibition-era fad of free verse but justified it by a brilliant narrative conceit.

And that’s why Marquis is forgotten now: because he was funny, light, and really, really good. Creeley is celebrated because he was Marquis’s opposite: a ponderous, self-important fool who made other fools feel much more important and wonderful than they were.

It’s a depressing story, confirming what a French cynic said about Bergson: “If he had not written so well, he would still be read today.” The moral of this grim chunk of forgotten literary history is that poetry is for suckers, humorless drips who can’t see the magnificence of the light touch but swoon for slowed-down, pompous declamation.

Most of you already knew that. But I gave my youth to that rotten craft, and for me, exposing Creeley as a fraud who stole from a newspaper parody is a belated act of revenge.

One of the saddest lessons of the comparison is the reminder of how truly radical, how brave, confident and daring, the West was in 1916. Marquis’s poems are wilder, freer, funnier, lighter and weightier at once than Creeley’s. Creeley’s time was a great retreat, once which continues today. We will never stop running; it will be people speaking some other language who find their courage again, and they’ll do it over our dead bodies.

One sign of greatness is the light touch, the one you find in O’Hara, the Simpsons, or the archy poems. archy started as a running joke, pure parody. There was a lot of talk about “verse libre,” non-rhyming poetry in the teens—again, remember that it was a much, much wilder and more confident era than ours. Really good parody always starts from a deep appreciation of the parodied form, and like the great American film Army of Darkness, the archy poems manage to mock their genre while playing it absolutely straight, bringing it to new heights. Marquis’s poems are great free verse, showing the beauty and power of “vers libre”while skewering it.

The notion of free verse was irritating to the ordinary newspaper reader, and to Marquis too. And the public was right, the artists wrong here, as shown by the fact that nearly all lyrics, the verse form that actually matters to millions of people, still rhyme; non-rhyming lyrics have been tried over and over, but very rarely succeed.

Worse yet, most American readers got their impressions of the genre not from the few who were really good at it but from febrile hicks like Carl Sandburg, socialist clergy for the Church of Americana.

http://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/max-beerbohm-the-poets-corner

The titles of Sandburg’s first books are worth recording to get the pompous, liturgical tone of “the artless art”: In Reckless Ecstasy, Abe Lincoln Grows Up, and my favorite, Plaint of A Rose. For those who found Sandburg too Midwestern, there would soon be another, even less talented priestess of art to make the hicks giddy: Amy Lowell, worst example of a classic early Modernist subspecies, the wealthy dilettante with a vast ego and no talents other than self-promotion. The term “vers libre” was coined by Gustave Kahn, prototype of the subspecies, and maintained by Gertrude Stein, but for most Americans, “vers libre” meant the godawful poetry of Amy Lowell, typified by her oft-anthologized “Lilacs.”

Marquis had a healthy lack of respect for the new form, but he also understood its few strengths, probably much more than he himself realized. That’s how the best parodies work: they’re inspired by an ineradicable obsession rather than simple disdain. Marquis sat as his typewriter, watching the clock, hating the vers-libre trust-fund brats who could get more respect by hitting the return key in the middle of a sentence than he could grinding out coherent prose to give to the copy boy–and from sheer terror and frustration, one day in 1916 there emerged the cockroach archy.

From the start, archy had the quality you see in the best American art, the ability to go high and low at the same time, win both sides of the pot. Unfortunately, it’s not something the wretched poets could grasp, let alone appreciate. In the decline from Marquis to Creeley you see the Black Mountain Corps of Engineer’s Buddha-given task of concreting American pop culture’s glorious, wild high/low voice into a monotone solemnity, and the idiocy of what passed for high culture in mid-twentieth century America.

Creeley’s era even coughed up another Lowell, a new Lowell as it were, this one called Robert, who kept the family business going by flooding the hippies’ anthologies with ponderous dreck about his tedious 1950s psychology and divorces.

If you’re reading this and you’re young enough to have a future, stay away from poetry. Stay away from movies too, but for a different reason: they take too much capital. Find a genre form that doesn’t require million-dollar investments or get much respect but gets read, and argued about passionately, without attracting the notice of highbrow critics. Graphic novels might have been a good idea ten years ago, for instance, but I don’t know; the ones people send me now are too arty by far, too self-conscious and not really very good. The critics and the movie people got interested in them, see. You want to avoid that. Music is good and cheap, but there are others. PKD found pulp SF; Chandler found whodunits; Larsen took up Addams’s one-panel animal horror cartoons; and animation is getting cheap enough for people-phobes to use. If you’re young enough to be considering the possibilities, you know them way better than I do anyway. It’s your call. Anything, my god, anything, except poetry.

Read more: john dolan, poetry, John Dolan, Books, Fatwah

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

3 Comments

Add your own1. muffinpie | March 17th, 2009 at 1:46 pm

Cheer up, Dr. Dolan. Everyone else hates poetry too.

2. beeblebrox | March 17th, 2009 at 1:54 pm

I almost skipped this article because of the poetry quotes. I have a lit. degree from a UC and I don’t read poetry. Won’t do it. Can’t do it. I’ve never once experienced anything but boredom and loathing from reading verse. Maybe I’m a bad reader, or maybe all the poetry they assigned really sucked. Plus my teachers didn’t have much to say about stuff that wasn’t directly related to feminist careerism.

Someday they’ll say of Dolan, “If he hadn’t been so frickin’ awesome, he would have had tenure.”

3. wengler | March 17th, 2009 at 2:04 pm

I never understood poetry, especially free-form poetry, but I get what your saying. Good article.

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed