Man discovered by apes

When I think of the 1990s, it’s the Ice Man I remember. He was found in 1991, in an Austrian glacier melting from global warming. At first the authorities took him for a murder victim (it was Silence of the Lambs time). They hacked his body out of the slush with a jackhammer, eager for their CSI moment, then started to realize he didn’t fit the profile of a Hannibal Lecter scorecard. His shoes were made of bearskin and deerskin and stuffed with dry grass; his cloak was woven of grass; he carried a flint knife that looks like a folded, dented can lid tied to a stick with twine. It began to dawn on the investigators that this guy was old, pre-war (or so they thought). Tourists swarmed him; fungus started to grow on his greasy amber hide (his outer layer of skin had come off long ago) from their eager, sweaty little hands. The Austrians finally announced that carbon dating showed the corpse was 5,300 years old. At that point Italy and Austria tried to have a nineteenth-century dispute about who owned the ex-glacier, and thus the body. But this was Europe in the 1990s, without the energy for another War of Jenkin’s Ear. The Austrians kept it, and in true 90s style the only fights were in court, between the hikers who found him and the government, and came down to money.

The hippies tried him on first. After all, he was wearing all those hemp clothes. And he was clearly alterno, because he had tattoos, little dot patterns on his lower back and right knee. Stoners from Amsterdam to Taos fried their brains with the question: What would a 5,300-year-old New Ager be doing up on a glacier? And realized that there was only one explanation (snowboarding was rejected as ahistorical): the deceased was, had been, a shaman. On a vision quest. They knew their Native American mentors (the ones in the movies, anyway) sent their spaciest dudes up into uninhabitable territory so that frostbite could work its mind-expanding magic. Clearly, and despite his regrettable leather footwear, what we had here was a dedicated Seeker who sought a little too high, a little too cold, and slipped into the big sleep. Another casualty of expanded consciousness, like Hunter Thompson’s lawyer, who demanded to be electrocuted screaming, “Tell them I just wanted to get higher!”

Then came the autopsy, and suddenly the corpse belonged to a newer, stronger next of kin: the Ice Man was gay. Because “they” found sperm in his frozen, folded anus. This was by far the biggest impact the corpse could have had on mid-90s popular culture. It was too good not to be true. Ellen was coming out, and now the Ice Man. It trumped the Bible by eons. Before those Levantine schizophrenics even started their censorious, homophobic gibbering, gay Austrians were having joining the gay mile-high club.

Notice Ice Man’s backwards facing position…

It was like finding a lost deed granting title to the youngest, most confident claimant. Joy was unrefined.

That’s when the Ice Man entered the airless Business School classroom where I taught Creative Writing in New Zealand. Somebody submitted a poem on the corpse, not mentioning the gay angle but just gloomily commemorating it—a depressed poem trying to find something to celebrate and finding it in a corpse that at least didn’t decay.

But that angle was of little interest. The gay lobby, in the form of Christy, claimed the body as soon as the poem was read in class: “Yes, and he was GAY! They found another man’s sperm in his arse! The Ice Man was GAY!”

Christy was our resident lesbian activist. Every 90s writing group had one, and Christy suited the role perfectly. She was about five foot nothing, ash-blond hacked hair and minimum flesh on her sharp little bones—but what a voice. Christy never spoke below a hundred decibels, and her tone veered between denunciation and embrace. You were either with her or against her, depending on your position on a few key issues. And the greatest of these was gayness.

It’s funny thinking back on what “gay” meant in the 1990s. You’d think the Ice Man would be claimed by gay men, but…what gay men? I grew up in the Bay Area in the disco era; I remember when they defined gay. But in the seven years I taught creative writing, from 1995 to 2001, I don’t remember any male students who were willing to announce themselves as gay. They were there, but lying very, very low. Whatever new freedoms that decade brought, they didn’t include gay men. Maybe it was an anomaly, specific to New Zealand, where men have to be blokes or nothing, and women…well, women have to be blokes too, unless they want to embrace the utterly thankless role of the female heterosexual in Rugby culture, which features a level of misogyny I’d never seen before heading down under—“girl” is an insult there.

Which makes it a great place to be a lesbian, and Hell for gay men. Not to mention that the bravest of them were, well, dead. Thom Gunn, the only brave man I ever met at Berkeley—no, he wouldn’t have been dead at that point, but he was dying.

So Christy had no competition when she claimed the Ice Man as gay Adam. I remember her voice blasting through that classroom. The rooms in that building were the most expensive in the entire university. It was the new Business School, after all, the spoiled child of the new generation of academic managers. I hear it’s bankrupt and almost empty now.

Instead of windows these classrooms had banks of metal shutters, dozens of them, each equipped with its own engine, about the size of a Walkman. The shutters were wired to the fidgety thermostat, so that halfway through somebody reading a poem, usually at its most sentimental or delicate moment, the room would fill with a huge whirring, as the shutters decided to open or close. And when they were done, they’d finish with a huge sucking sound as the airlock closed.

It wrecked many a pronouncement, but Christy was never fazed. She had a huge voice; it was the voice for its time and place. It fit right in there. And she got a respectful silence when she claimed the body of the Ice Man. Nobody would have been so stupid as to quibble with any pro-gay statement in public; there were places for that. Pubs, parties. New Zealand culture features more kinds of silence, more nuances of non-response, than the alleged Inuit and their alleged 26 words for snow. The silence that absorbed Christy’s announcement was formal, cautiously gratified; an opportunity to demonstrate correct thought had arisen and been accepted. Christy made her point again, the shutters did their noisy chorus, and we moved on.

But it can’t have been so easy for Christy after all, because a year later she was dead. Very murkily dead. There were a lot of murky deaths in Dunedin. The attitude there reminds me of my parents’ beliefs about language: it’s a sport, a pastime, but when something is really important, it is never, ever to be mentioned. So Christy just died; an accident, or drink, or a fall. She had been abused, they said, as if that was why she died.

Then the man who’d written the poem about the Ice Man died. He was older than most of the students, a longhaired local who’d never gone very far from Dunedin. Americans have trouble understanding—I had trouble understanding—how, in a culture that doesn’t reward egotism, lives can just shrink and shrivel to nothing. Californians like me tend to expand until they burst and die with a comic balloon Ffffffpppt!; New Zealanders, especially the men, just discipline themselves until they just aren’t alive any more. Although this guy took some killing, he didn’t just die. He went off into the woods and hanged himself.

He’d always been very friendly with the group, but there was something off about him. Depression isn’t attractive except in the movies; it’s annoying. He was annoying, ten years older and sucking up to everybody, out of it, old hippie. He volunteered to hold the end-of-semester party at his house. It was not a success. The house was bleak even by local standards, and in the cold monsoons of Dunedin his nervous smiles, his patchouli-stinking stagnant rooms, brought everybody down. It was the kind of house that needs to be burned down, the kind of life that would be helped by conscription in an army, any army.

Once he was dead, he became a more sympathetic object of contemplation. It was clear why he’d so desperately invited us to his wretched house in the rain: he was trying to find a reason not to hang himself. It followed, then, that he must have been trying to find friends in our group—friends! Among a bunch of poets! No wonder he died.

And it was suddenly, equally clear what had drawn him to write that poem about the Ice Man. At a conscious level, it was that lethal hippie cant—hemp shoes, shamanistic nonsense—all the flabby Aquarian lies, to borrow Leonard Cohen’s phrase, that had sent his life down that lousy, rain-sodden cul de sac. And beneath the surface hippie ideology, the real attraction: the fact that the Ice Man was so dead, so dead-dead-deadsky.

But it was hard to be very sympathetic for very long. He was too annoying, even in death: it seems that when he went off to hang himself, he’d left a note telling his friends to stop smoking.

The Ice Man ushered out the Nineties as brilliantly as he introduced the decade. He had one last, biggest post-mortem epiphany in him. It arrived via X-ray: they found an arrowhead embedded in the Ice Man’s chest. A bit of a surprise, isn’t it, that it took several years for scientists to notice an arrowhead embedded in the body of the world’s most autopsied corpse. It’s as if they were…well, you know: stupid.

All the fondest dreams of the Ice Man’s fans were suddenly X’d out. That little sliver of flint killed them as surely as it killed him. He died because somebody goddamn well killed him, meaning e wasn’t a shaman too spaced to bundle up. He wasn’t an alpine Ellen, a wandering Whitman. He was a killer himself; there was evidence on his knife and arrows that he’d killed several people before they got him. And they got him good. The wound was expertly inflicted; according to pathologists, it would have been fatal even if he’d had access to 21st-century medical care. He’d been ambushed.

And if another man’s sperm was indeed present in his ass, it wasn’t friendly sperm. The Romans used to do that when they took a city. A way of reminding the defeated who won.

Who claims the Ice Man now? It’s like a punchline: “Who do you want?” As far as I know, he’s available. You’ve just got to want him.

The only reason to state the moral explicitly is the moral itself: we don’t have a clue. We won’t get the point if we can possibly help it. Stratum after stratum of vicious cant and obvious lies, cheered and shelved, immunity for all past lies. Except that along the way people do tend to die for what they believe. Everyone dies for what they believe. When you consider that, the way we die for stupid, transparent cant, well…you know, those suicide bombers don’t look so bad.

Which is odd, because I just remembered that the last time I taught that course, in 2002, there was a whole slew of poems about the horror of suicide bombers. I remember somebody saying, “I just can’t understand the mentality of someone like that.”

Read more: america, culture, gay, ice man, poetry, John Dolan, Fatwah

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

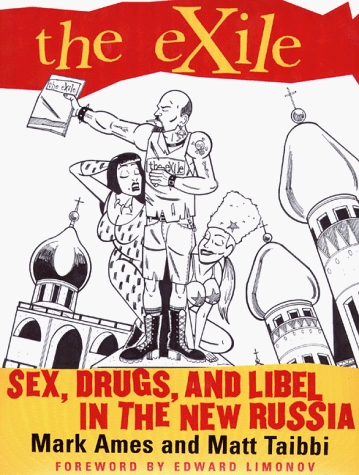

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline