Faced! Wheelchair-bound eXiled Editor Yasha Levine finds out that in Russia, provincial clubbing ain’t for cripples

Editor’s note: We reprint this eXile Classic, first published in The eXile on September 25, 2007, to commemorate Russia’s recent triumph in the Vancouver Winter Paralympics, in which it won more medals than any other country. And to think that just a few years ago, they weren’t letting cripples into IKEA. Authoritarian Russia sure has come a long way…

“In the USSR, there are no invalids.”

This was the official reason that the Soviet authorities gave for declining an invitation to hold the 1980 Paralympics in Moscow. If you’ve spent any time in Russia, you might think they were telling the truth.

Other than a few token amputee Afghan vets begging in the metro or haunting traffic during rush hour, disabled people are simply not part of the Moscow landscape. After three years in Russia, I can count the number of wheelchair-bound people I’ve seen on one hand.

Obviously, just because they’re not out in public doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. If anything, it points to how bad the handicapped have it. There are approximately 13 million people living with serious disabilities in Russia, according to Perspektiva, an NGO that fights for disabled rights. Out of a population of 140 million, about 10% of Russians are considered handicapped.

So why are Russia’s handicapped so conspicuously inconspicuous? Are their lives so traumatizing that 10% of the population would voluntarily place itself under house arrest rather than face Russian society?

There are many ways to tackle an issue as painful and disturbing as this, so I chose the most painful, yet lightning-quick angle possible: get my own Russian wheelchair, go native, and do the Disabled Like Me story. My plan was try to spend a day doing a range of typical 20-something Russian activities—ride the metro, go to the IKEA mall, eat at a shitty sushi chain, go clubbing—all in a wheelchair. The rules were simple: no leg movement the entire time. Among other things, this would bring into focus all the basic problems that a wheelchair-bound disabled person would face. Would I be able to wheel myself around alone? How would I use the metro? How about a bus? Would the goons who guard every store and restaurant even let me through the door?

By law, it shouldn’t be so horrible. In 2001, President Putin signed a law mandating equal access for the handicapped on public transportation, in government-owned buildings, and all newly-constructed buildings or those that have undergone major reconstruction. However, the reality is that since the laws have no fines built into them, there has been very little compliance. In fact, even many Russian hospitals aren’t handicap accessible.

After spending a full day wheeling around in my wheelchair, what I learned wasn’t at all what I expected, in ways that are both more life-affirming and suicide-affirming. On first impression, Moscow, especially its people, was much more welcoming to the handicapped than I had expected, or experienced back home. But as I dug deeper into the everyday reality that invalids face, I found out how brutal a life it really was.

A CHAIR CALLED “HOPE”

My first order of business was getting a wheelchair, which I rented from a store called Invalid Technologies located near the MKAD. For 250 rubles per week, I was able to rent a Russian-made wheelchair manufactured in Ufa. My wheelchair was a “Nadezhda” brand, which means “Hope” in Russian. A wheelchair named Hope. It’s the kind of over-the-top black humor you’d expect in an old Zucker brothers comedy, especially when you consider that almost every part of the chair is constructed in the shittiest way imaginable. The only thing manufactured decently is the giant “Nadezhda” brand tag.

According to the guy at the store, despite its good looks, the Nadezhda wasn’t really an improvement on the chrome Soviet-era wheelchairs that are still given out to the disabled by the Russian government for free. It had faulty breaks that would lock up without warning, and the wheelchair wouldn’t stay in its collapsed position no matter how hard I and my “nurses” tried. Moreover, the damn thing weighed 50 pounds—more than a third of my body weight—making it useful for mafia thugs looking to sink a body. For me, the Nadezhda was about as difficult to steer as an APC. The chair’s only innovation was the deluxe bright blue paint job and removable leg braces, which supposedly made it highly transportable. Transportable on what, is the big question—a C-130 Hercules? As I found out minutes after leaving the store, my Nadezhda didn’t fit into the trunk of any standard four-door Lada produced in the past three decades, and it barely even fit into a Lada’s entire back seat.

WHEELING ON THE METRO

You don’t really appreciate the speed, vertical slope and mineshaft-like distance of the Moscow Metro’s escalators until you’re staring down one from a wheelchair. The things cook, like George Jetson’s treadmill.

But I had to take the metro. One reason is because the disabled don’t really have much of a choice. Access to government-subsidized automobiles had been cut off a few years ago when a decades-old Soviet-era law requiring the government to provide handicap-accessible cars, such as the little Oki death traps, to the disabled expired in 2005, and was never renewed. So it was off to the metro.

Alex Zaitchik acted as my nurse/guardian for my first foray out. It was relatively easy getting through the newly installed handicapped-friendly turnstile in the Belarusskaya metro station, but when we got to the escalator, we stopped and stared, genuinely worried, like a kid before his first high dive. Would we make it? Or would we tumble down?

Zaitchik had recently thrown his shoulder out playing baseball with some competitive-corporate types, so he wasn’t very confident about his ability to support the 200 lbs of me and the Nadezhda. If he was worried, then I was starting to shit bricks. One wrong move and I’d be tumbling down hundreds of feet of sharp-edged escalator steps, with Zaitchik twisting into the Nadezhda’s axles the whole way down. Pure cartoon slapstick—only with lots of live-action blood.

I’d seen how real handicapped people manage it: just before reaching the escalator, they’d swing their wheelchair around to face backwards, move closer to the escalator edge, grab ahold of the handrail treads, and let it move them back onto the escalator. This way, they use gravity to their advantage, but the disadvantage is the unpleasant experience of riding down a long, steep elevator backwards, and at a steep angle, on a faulty wheelchair.

Alex and I borrowed their technique: I turned around to face backwards, Alex hopped onto the escalator ahead of me, and grabbed my wheelchair handles, easing my transition onto the fast-moving steps. At first, Alex miscalculated the speed of the escalator, and for a spilt second, I was left myself wobbling at the very peak of the escalator with no support from behind. As I teetered over, I grabbed onto both banisters and managed to delay my spill just long enough for Alex to come bouncing up the escalator to support me. We made it, but I’m never doing that again.

To transfer trains from the circle line to a radial line was the next big obstacle, since it meant going up non-moving stairs. Zaitchik is big healthy guy, but even he had to quit after only hauling me up two stairs. There was no choice but to break the rules of this story, get off the wheelchair and roll it up the stairs myself. Already it was becoming clear why you don’t see handicapped people in the subway system.

For the most part, my presence didn’t cause any problems. Most people stared at me, and no one moved out of my way when I needed to get off the train, until I started spearing their ankles with my chair’s steel foot braces, the Nadezhda’s lances. Then the assholes got courteous and respected my special needs.

THE MALL

If there’s one positive thing to having Moscow’s super-malls on the outskirts of towns, it’s that all that space allowed them to be more wheelchair friendly than other parts of town. Most of these outer-ring Moscow super-malls are wheelchair accessible, making the IKEA superstore and the Mega Mall on the cutting-edge of universal access in Russia. In my interviews with Russian disabled-rights organizations, they too gave the malls credit for making life better for them. Once at the mall, I wheeled myself through the wide, smooth-tiled floors of Mega Mall towards Starbucks—and for once, the Nadezhda started to live up to its name.

I was trying to gauge the Russian mall-public’s reaction to me, a handicapper wheelchairing into their perfect watercolor shopping mall. Would they look away in horror, treat me with disdain, pity me, fear me? I was too low to the ground to get a good read, but Zaitchik said that many of the mall-trolls were openly gawking at me. Some even stopped and stared. Kids were the worst, openly pointing straight at me, although some grownups were just as bad. I spotted several couples in which one would nervously tug on the other to get a look at me.

That didn’t surprise me. But then, Alex noticed another type who stared openly at me—chicks. Young, cute chicks, to be precise. They weren’t looking at me with disgust or pity. It was more like unhindered curiosity, with a hint of desire. Even the bright red blanket I draped over my legs to give me sort of Cancer Boy look didn’t bother them: these chicks were checking me out. They were digging a cripple! What the hell was going on?

According to the people at Perspektiva, Russians have a laundry list of negative stereotypes they associate with the handicapped. Disabled people don’t have sex; they can’t go to school, work, drive cars or do anything even remotely active in their lives. Basically, if you’re disabled, you’re expected to live differently and separately from normal society. Most importantly, most people assume that if you’re crippled, you’re a heap of miserable emotions.

Probably because I didn’t have the sickly pallor of a typical handicapped person in this country, and instead looked healthy wheeling around, drinking a venti Latte from Starbucks, the girls’ expectations were pleasantly upended, and that happy surprise eventually morphed, as most things do here, into sexual desire. Being wheelchair-bound also made me eccentric, which Russian girls tend to like—maybe I was a kind of mystic with special powers? Or more to the point, how much cash did I have to make me so happy? Whatever glow my Nadezhda was giving off, it worked magic on the girls.

On the way back, we tried to catch one of Moscow’s new handicapped-accessible buses by waiting at a bus stop on Leningradsky Prospekt. After two hours, we gave up on it and took a cheat-taxi home.

I didn’t get to test the bus myself, but I did talk to some handicapped people who have, and they had nothing but praise for it. As a journalist, it’s no fun reporting when things are working and improving, but the new buses clearly are a huge step forward, even if there are only a handful of them in the entire city.

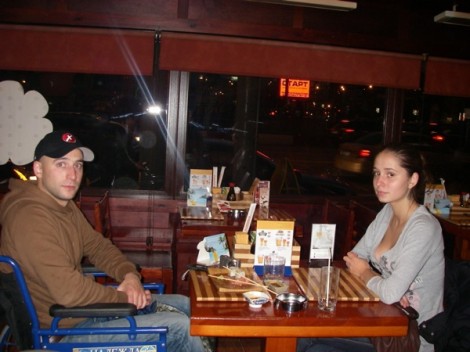

DINNER DATE

For dinner, I had my girlfriend wheel me over to Yakitoria, which is like the Jack In the Box of Russia’s crap low-end sushi scene, with restaurants all over Moscow and beyond. It was a hit with the first wave of emerging Putin-era middle class Muscovites, and it’s still a hit with ever-lower and younger segments of that middle-class. I’ve avoided Yakitoria like the plague, so I had no idea what to expect when I got there. Would they face control me? Could they seat me, or were all their chairs and tables bolted to the floor? Would patrons point and stare at me, or throw shit at me, or take their photos with me?

Just as my girlfriend was helping to push me up to the restaurant door, a drunken middle-aged man accosted me, and forced me to take from him a 50 ruble donation.

I thought it was because the guy was drunk, but in fact it was the first in a series of heart-warming moments, of Muscovites going out of their way to help me and make me feel comfortable, something I didn’t expect. The okhranik at the door, who was dressed more like a geisha than a samurai, helped my girlfriend push me up a few stairs to get to the restaurant’s front double doors, where a waitress quickly scrambled to remove a chair from a table nearest to the door so I could maneuver inside. The place was busy but no one seemed to take much notice of me. Apart from a few giggles coming from two drunk bydlo women sitting across for me, everyone else treated me with the utmost consideration, and without the usual shame, fear and turning away you get in America.

NIGHTCLUBBING

This was going to be the final and most brutal test of them all. How would Moscow’s clubs score in the disabled-sensitivity scale? I’ve never seen anyone with a disability—even so much as a stutter—hanging out in a Moscow club. (Although Ames claims that he and Krazy Kevin once took home a couple of deaf girls from Papa John’s in the post-crisis era.) I was betting on getting faced every single time.

It was a good thing I didn’t actually put money down on that.

Here was the rough plan: I figured it would be better to make a real effort to get into the club and experience it inside as well as out. The eXile shareholders agreed to spring for a brand new, sleek Mercedes minivan for the night. I prettied up my Cancer Boy look by wearing the two most expensive items in my closet: a Calvin-Klein sweater and sports coat, both of which stopped being fashionable about four years ago. And I rounded it out by hooking up with two non-wheelchair-bound, well-groomed clubbing partners, a finance guy named James and former eXile editor Jake Rudnitsky.

To press some advantage with the face control, we’d have the Merc driver pull up right in front of the face control line. Then, in full view of the bouncers and crowd waiting outside, James would lift me out of the van, throw me over his shoulder with my legs dangling, and then gently place me into the Nadezhda wheelchair. We wanted to make the cool “leggist” crowd feel uncomfortable, and figured the more spectacle they’re forced to watch, the better for us.

The first place we visited was the Denis Semachyov Bar, the hip new elitny bar on the boutique-packed Stoleshnikov pedestrian street. I didn’t expect to be let in to this fashion-world tusovka. The bar is no bigger than my living room; there is barely any room to stand, let alone wheel around in a tank like the Nadezhda.

I couldn’t roll the wheelchair on Stolechnikov’s retro cobblestone streets, so James pushed me up to the entrance. There was no line at the door, but the bouncer politely told us that we couldn’t get in as there was a private party going on, the nice way of telling you DENIED. We could get in only if we were on the list.

Funny thing is, I was on the list, since somehow my cellphone got on their PR list, and I receive almost daily SMS invitations to the bar. But on that day, for some reason (one that probably had nothing to do with me being in a wheelchiar), my name had disappeared. After a bit of wrangling, I produced the SMS that proved my membership, and that was enough to grant us entrance. The two guards even scrambled to help James haul me up the two gigantic steps.

Inside, the Semachyov bar was pretty beat. Nothing much was going on, and I was being ignored rather than laughed at or whispered about. I worked one cocktail, rolled around the entire length the bar, lanced a few patrons’ ankles, and then we split.

Our next stop was Zona, a crap multi-floor dance club considered elitny by the podmoskovie bydlocrowd who made it their own Dyagelev. It was Zona’s mockery of invalids that first made think of taking the Nadezhda out clubbing in the first place. When Zona rebranded itself as a high class club, it posted proudly on its website that it had a “no invalids” face control policy. They’ve since taken that rule off the website, but in practice, it remained it full force.

Our Merc rolled up right to the VIP ticket booth. But after getting placed into my chair, I couldn’t even get off the road and onto the sidewalk, thanks to metal anti-riot barriers blocking the way.

“We don’t allow invalids into our club,” explained a pudgy okhranik who called himself an administrator. Explained not to me, but only to Rudntisky: non-invalid to non-invalid. We protested and demanded to see his superior, but that guy was even more aggressive and goonish. He wouldn’t explain his reason for denying me entrance, insisting only that it had nothing to do with my invalid status.

We hung around outside with two chicks who also got faced, but I wouldn’t give up. So I followed the senior “administer” as he dealt with a Caucasian patron who had stumbled outside and puked all over a car next to the VIP ticket booth, spoiling the whole elitny atmosphere.

“Why aren’t you letting me in? I want you to tell me the truth to my face, man to man. Is it because I am a cripple?” I asked him.

“I don’t have to tell you anything, especially not the truth. But I will tell you this: you and your friends are acting uncouth.”

We finally left for Fabrique, a popular semi-elitny club which usually has an eXile-friendly policy. The club’s interior is an architectural nightmare for the handicapped. Its two levels with sunken dance floors and maze-like rooms connected by tiny spiral staircases become dangerous just after a few drinks. Fabrique was definitely not designed for the disabled-tusovschik.

When we arrived at the door, we decided to cut past the crowded line in front. Rudnitsky aggressively told the bouncers that they should let us cut, and they responded with looks of total confusion.

“We’re not geared for wheelchairs. Come back when you’re feeling better, which I’m sure will be soon enough,” the senior bouncer said without hesitation, looking down at me.

“But I’ll never get better,” I replied loud enough for the whole crowd to hear. He ignored me, but a few snickers could be heard from the clubbing crowd gathered outside the entrance.

Seeing that we weren’t going to get far, we gave up and headed to Vodka Bar at around two o’clock. At first, the guards tried to dissuade us from entering by explaining that it was too crowded to guarantee my safety. But after some pleading, they yielded and wheeled me through the service entrance.

Surprisingly, Vodka Bar turned out to be almost completely wheelchair accessible. For the fist time, I could wheel myself uninhibited around the entire club. And this is where things got really weird. Within no time, I became Vodka Bar’s beeyatch magnet. Girls were on me like mayonnaise on Russian salads.

“You’re so brave! I think it’s great that you’re trying to go clubbing. You’re such a hero that I have this desire to marry you right now!” screamed the first girl I rolled up to, after she wiggled her ass for my benefit.

When she went to the bar, a second dyevushka, a 30-something Kaluga-looking type, demanded that I pose with her for some photos and then give her a ride around the club. Every time I tried to wheel myself away from her, she’d find me and force me to freak with her.

As soon as she turned her back, another girl snapped me right up. She grabbed my hand and dragged me to the bar, hitting about a dozen people with my steel leg braces along the way. Then she did something that has never happened in the annals of Russian dyev bar manners: She bought me a drink. With her own money! After handing me a gin and tonic, she plopped down on my lap and tried to shove her tongue into my throat. Disgusted by her alcohol and cigarette breath, I winced and pulled away. She didn’t know how to take it. A cripple turning her down? How does your self-esteem ever recover from that?

“Do you have a girlfriend?” she asked suspiciously.

I just shook my head and told her that I don’t get out much and that I only came to dance. Which I did, wheeling the chair this way and that on the dance floor, where I was stolen away by yet another dyevushka, who trumped the French kisser by mounting my wheelchair, and riding me, literally riding me, into her arms.

***

This story was first published in The eXile on September 25, 2007.

Read more: clubbing, cripple, eXile Classic, exile issue 272, moscow, Russia, special olympics, the exile, wheelchair, Yasha Levine, eXile Classic

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

9 Comments

Add your own1. Jack | March 23rd, 2010 at 8:00 pm

Great classic!

2. MB | March 23rd, 2010 at 9:06 pm

Ochen horosho

3. Russian Dude | March 23rd, 2010 at 10:10 pm

Go Russia! The Paralympic athletes made us all proud, and they deserve to be treated humanely. Now that we have our country back in order, everyone’s getting better treatment, except for those poor, poor Oligarchs. I heard it’s the other way around in the US of A; but then again, the USSR is the opposite of the USA.

4. Eddie | March 24th, 2010 at 7:11 am

get some!

5. Niels R. Gislasen | March 24th, 2010 at 7:49 am

Great coverage! And the ending very funny, although it’s sad that the wheelchair hero that want’s to change the world can actually stand up when he feels like it.

Thanks.

P.S. (Iv’e been trying to send e-mails to @exiledonline but it doesn’t work. Anyone know what’s wrong?)

6. Rubicon | March 24th, 2010 at 12:34 pm

I guess it proves you have to have guts and just be willing to go out there. Of course, you need some friends to help too, since that was rather a beast of a wheelchair. The only bad part is that some actual wheelchair-bound schmuck will get crap because everyone will think he’s faking it. But at least you proved that even handicapped guys can get some action.

7. timmy | March 24th, 2010 at 5:26 pm

A brilliant late Russia era eXile classic!

Sorry to abuse the comment section for this article to say this, but I have to comment on the Lithuanian Wendel master in the news links, am I the only person who wondered for years (i’ve been reading the eXile since the NATO Kosovo) what exactly wendeling was? Some time or other way back when, I looked it up and could find anything. It was something sexual – something mysterious, funny and humiating that happened to nubile young dyevs. Letters to the eXile would often be answered with a polite request to let Ames wendel either the letter writer, their girlfriend, daughter, etc. Or the hapless corespondent would be informed that their special someone had, indeed, recently been ‘wendeled’ by Mr Ames.

Now I kind of wish I hadn’t found out the facts of life, if you will, about wendeling. Could any real life sex practise live up to the mystique of wendeling? All the mystery of sex has gone these days it seems, but there was one secret still until only a short while ago. Now that secret is gone, and what is left?

8. CapnMarvel | March 25th, 2010 at 4:30 am

Classique. All of the eXiled’s old niteclub-punking missions were epic, and this definitely counts. So many attractive, drunken dyevs. So many feiskontrol goons. So many 180 rouble Heinekens. Aww, man…why did I ever leave you Piter?

9. RecoverylessRecovery | March 29th, 2010 at 12:00 am

You need to pimp-out that wheel chair of yours my brother!

I’m talking double chromed rear-view mirrors, full upgrade to some spinning-rims and throw a little fuzzy blue velvet over those spartan armrests tovarich. Fo’ shizzle!

Don’t forget the high-end Bose boom box heavy on the base tucked under the seat for added vibrational effect.

Maybe even get one of those little pinecone air-fresheners ..just in case another hygenically-challenged девушка decides to give you a full face-forward, open-legged lap dance again.

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed