Before heading back to Moscow in June 2008 to face the Kremlin “audit” of The eXile, which I knew meant the death of the newspaper at the very least, I worked out a deal with my editors at Radar magazine to blog about it for an American audience. I hoped at the very least that it might give me a bit of protection.

Radar was the only great print outlet in America, which is why it was doomed to collapse–it’s since been taken over by a celebrity gossip site. I went through the cached archives and found the old blog posts–here they are, in chronological order:

A TROUBLESOME VISITOR

With the recent inauguration of new president Dmitry Medvedev, how have things changed in Russia? Is the authoritarian freeze of the Vladimir Putin years starting to melt into a glorious new spring of freedom? Mark Ames, founder of Russian newspaper the Exile (and Radar contributor) will provide occasional dispatches in pursuit of an answer to that question … if the authorities don’t lock him up first.

June 9, 2008

Thursday morning, Moscow time, four Russian government officials came to the office of my English-language newspaper, the Exile, and conducted an “unplanned audit” of our editorial content. They are carrying out an inspection of my paper’s articles to see, in their words, if we have committed “violations.” And they specifically asked to question me, since I’m officially listed as the founding editor-in-chief.

I started up the Exile 11 years ago with a Russian publisher, and it grew into a kind of cult phenomenon, with an online readership of 200,000 visitors per month, launching the careers of Rolling Stone‘s Matt Taibbi and the “War Nerd,” Gary Brecher, but ensuring that anyone who sticks with the paper is condemned to a life of poverty and paranoia.

In all my years I’d never heard of an “unplanned audit” of editorial content. The insiders whom I contacted all said, “It’s … strange.” That’s how my Russian lawyer reacted, it’s how an American official reacted, and it’s even how the head of the Glasnost Defense Fund reacted, even though his NGO focuses on problems between the Russian media and the Kremlin.

“As far as I know, there has never been a single Moscow-based media outlet which has been audited like this,” Glasnost’s lawyer told me. “We’ve seen a few of these in the far regions, but never Moscow. But really, don’t worry about it, Mark, I don’t think you’re in any personal danger at this point.”

Whenever a Russian tells me, “Don’t worry, Mark,” or, “It’s no problem,” I start to sweat.

I first learned of the government audit last week while I was out in California dealing with a family illness. I was already in a heightened state of paranoia at the time—one week in my native suburbia is all it takes to trigger panic attacks—so when the government sent notice of the “unplanned audit” to our office, my first thought was, “Can an American get political asylum in his own country?” Then I remembered some of the articles I’d written from Moscow—for example, my post–2004 U.S. presidential election editorial titled “Gas Middle America,” and how former U.S. congressman Henry Bonilla (R-TX) once used his office to pressure the Russian authorities into arresting mebecause of a prank I’d played—and the next thing I knew, I was rifling through my mother’s medicine cabinet looking for something strong to steal.

Eventually I calmed down and flew back to Moscow in time for the audit. At 11 a.m., four officials from the Federal Service for Mass Media, Telecommunications, and the Protection of Cultural Heritage arrived—the men in shabby Bolsheviki suits, and a squat middle-age woman with pudgy arms and hands that pinched the seams of her wrists. On the advice of a Russian attorney, we greeted them with a box of dark chocolates. It was solid advice, and probably did more to protect us than a hundred attorneys’ briefs could have.

The Exile‘s office is in a radon-poisoned basement in an old part of downtown Moscow called “Clean Pond,” which refers to a toxic puddle in the center divider of a nearby road. The office is so small that we have to take shifts showing up for work. So it wasn’t easy fitting the four bureaucrats and the few Exile staffers who turned up.

The varied emotional responses to the meeting were interesting. The Westerners, who until last week supported our paper and kept it alive, immediately cut all ties with us, so they weren’t there. The younger Russians on our staff were relatively calm about it. But when our Soviet-era accountant opened the office door and saw the four squat figures in bad official Soviet outfits, she turned white and vanished, the door closing on its own. When our middle-age courier arrived, she too turned white, stopped, then put her head down and walked past us, crossing herself three hurried times in the Orthodox Christian fashion before locking herself in the design room. You have to understand, to anyone with a memory of the Soviet era, those bad suits that the officials wore are extremely menacing, like red stripes on a reptile.

Their very first question was about the writer and opposition leader Eduard Limonov, one of my newspaper’s star columnists since the beginning. It’s not surprising—the Glasnost Fund people thought that Limonov would be their main focus. When I told Limonov about the audit, he seemed proud of me, kind of like how the Goodfellas gangsters greeted the teenage Henry Hill after his first trial: “Well, it’s finally happened!” Limonov said. “You should prepare to be taken to a stadium somewhere, like they did in Pinochet’s time!” he said cheerfully.

The officials asked us why Limonov was in our paper. Did we know much about him? Why did we publish him? Why was he on our masthead as a contributor? They asked to see an example of a recent Limonov column—the first one I pulled out was titled “Mr. Limonov on Mr. Medvedev“—I quickly shoved it under a pile and grabbed the next column I could find. They took that issue, and two others, with them, and told us that they’d have experts translate and check to see if we’d violated laws on printing “extremism,” “inciting national hatred,” “pornography,” and “pro-drugs propaganda.”

Here are a few of the Limonov lines from the article I gave to the officials, written in his trademark broken English: “Russian Government is bloody beast eating human flesh. It is deeply medieval in its principle conceptions … Russian women are very, very bad. The worst of all. Russian women is like the Russian Government. Millions of bitches walking our streets. I am absolutely and positively on the side of Muslim strict code of behavior for women. Their system of separation of sexes if effective and healthy.” Imagine now that you’re a Russian government official tasked with reading this column. Because I sure imagined it. And then I imagined them sending me a new notice, which is why a voice in my head started whispering, “There’s no place like home …”

Next, they asked us to explain our newspaper’s editorial style and concept. It was a good thing that our gorgeous young sales director, Zalina, was speaking for me, because how do you explain to a Russian bureaucrat that a newspaper whose motto is “vanity and spleen” is a low-tech suicide bomb designed to destroy our journalism careers and take down a few assholes with us?

After a difficult and failed attempt at explaining ourselves—a subject they came back to a couple more times—they said that some unspecified Russians had filed complaints about the Exile because it supposedly offended Russians, and mocked and degraded Russian traditions and Russian culture. What did we have to say about it?

Zalina, bless her heart, defended me: “No, Mark loves Russia and Russian culture! Really!”

All four of them turned and looked at me; I could feel a cheesy grin straining over my deer-in-the-headlights expression. Ahem … is this mike on? Hello? So, anyone here from Tomsk-7? No? Tough crowd.

In my opinion, this is the real reason they’re moving to shut us down. What offends the Russian elite more than anything about the Exile is its aggressive refusal to play by the “serious” rules. The authorities can deal with serious print-media criticism of the Kremlin—so long as that media outlet makes everyone look serious and respectable, with serious dull language quoting serious dull think-tank analysts. These days, Russia is all about getting serious and respectable. And it’s also in the grips of a national persecution mania, in which grievances and complexes about the West have exploded into a kind of mass grievance obsession, a frenzied Easter egg hunt for evidence of Western disrespect or unfairness in order to feed this grievance jones. The fact that our paper has also exerted a lot of bile in savaging the West’s Russophobe industry is irrelevant to them, even annoying; all they care about is sifting for evidence of humiliating Russia.

At one point in the three-hour audit, they started leafing through our February Barack Obamaissue, in which we posted a comparison chart of Russians and African Americans in order to tweak Russian racism (examples: “Blacks: Freed by Abraham Lincoln in 1863/Russians: Freed by Tsar Alexander II in 1861”; “Blacks: plastic covering on furniture/Russians: plastic covering on remote control”).

The lady-bureaucrat, who headed the audit team, leafed through the issue … and stopped when she saw a bad drawing of a semi-limp penis.

“What’s this?” she asked, putting her glasses on.

“It’s a column called ‘The Recession Penis,'” I explained. “You see, the Recession Penis reacts to America’s economic crisis, so every time American banks default and housing prices collapse, the Recession Penis gets more excited. It’s, uh, humorous, you see.”

She folded up the issue and handed it to her subordinate to bring back for the inspection.

From there, much of the meeting focused on all of the newspaper’s petty administrative fuckups: missing addresses, missing license number, something should be in Russian here, a registration number there. In all, the violations led to a $25 fine, which was levied on me personally as editor-in-chief.

The official with the mullet took over one of our computers and typed up a “protocol,” which essentially summed up our three-hour meeting. I signed it, only afterward wondering if in fact I’d signed some sort of confession admitting my role in a Trotskyite plot.

After all of the nervousness and fear in the buildup to the meeting, when the three hours were up and they got up to leave, we felt fairly confident. Too confident, in fact. Because today, I’m starting to think differently. I’m thinking this:

A: I live in a gangster police state that’s hell-bent on being respected.

B: These people are now auditing my articles to see if they’re extremist, pornographic, or if they humiliate Russia.

C: Before they left, they took our most recent issue, in which I wrote that the Exile “farts in Russia’s face” and that Medvedev is so liberal our paper can “urinate into the president’s mouth without any fear of consequences,” and he’s so small he should be “zipped up in a squirrel costume and put in a Habitrail.”

THEREFORE, D: The California suburbs are sounding pretty nice to me.

The Russians I consulted with before and after the audit all came to the same conclusion: The authorities are planning to either tame us or shut us down. There’s no more room for the Exile in the new serious/respectable Russia, the Russia of fanatical consumerism and materialism and vile conformism. This is a country where two separate magazines launched proudly billing themselves as the “New Yorker without political reporting.”

In the current climate, the authorities don’t need to jail or destroy you; all they need to do is notify you that you’ve earned their attention, and if you’re on their radar screen, then you immediately comply with whatever you think they want you to comply with, and you get abandoned by everyone around you who doesn’t want to get sucked into your vortex.

And if you do fight the law, then … well, just this past week there have been two examples of what can happen. The opposition webzine ingushetia.ru was closed by court order, and its lawyer had his apartment raided last week (I was planning to use him to help the Exile until that happened); and one of Russia’s largest radio companies was raided by armed police, leaving it temporarily off the air.

Now it’s like I have the Ebola virus. Longtime friends won’t call, contributors want their names expunged from the online record. Even the American media is eerily silent about this story, despite the fact that one of their own is being attacked—could it be because we’ve spent 11 years savaging the Western media here? Or because we once threw a pie filled with horse sperm into the New York Times bureau chief’s face? Just as a single controversial article in Russkii Korrespondent led its rather brash billionaire backer to immediately shut it down last month, so this single audit means that the Exile is now, after 11 years, dead.

The biggest fear of every foreigner in Russia is becoming the focus of Kremlin attention. Any attention. Russians fear it as well, but they’ve internalized it since birth and deal with it differently. Foreigners here operate with a kind of looter’s mentality: On the surface is overconfidence derived from the general sense that there is no authority over us because we think that the Russian authorities would never mess with a Westerner, but underneath that arrogance is a constantly bubbling terror of being stopped at the border, turned back, and subjected to Russia’s arbitrary and brutal state. It’s such an alien country to Westerners that it’s easy think you operate in some kind of H.P. Lovecraft–like parallel plane with the Russians: In one reality, the Westerners as the humans; in the other parallel reality, the Russians as those flying fanged eels. Now that my paper is being examined, it’s as if everyone around me suddenly grew a giant pituitary gland, and all they see are Lovecraft’s fanged eels orbiting around my head, snapping at anyone who comes near me.

Meanwhile, I’m still here in Moscow, waiting for the Kremlin’s experts to audit my dead newspaper’s articles.

* * *

THE END OF THE EXILE

June 10, 2008

The Exile is shutting down. Last night I met with my Russian publisher to “put one in its brain,” as George Romero‘s humans would say. Except that putting this paper down is not so easy—imagine if Romero’s zombies had things like tax bills that can’t be ignored, debts to pay off, favors owed to other important zombies—because you never know when you’ll run into that zombie again.

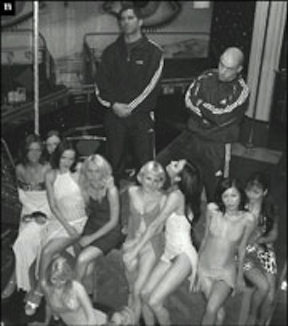

The partners who’d financed us fled for the hills, leaving my publisher and me holding the debt-bomb in our hands. This is not an easy situation. As a rule, my publisher is unusually easy-going for a Muscovite, but he’s also quite large and intimidating—I mean Baltimore Ravens defensive end large. He also runs a massive nightclub, and, well, let’s just say that my publisher knows a lot of people, including a pal of his who runs the Rasputin Gentlemen’s Club, a multi-floor fleshpot that is everything a male wishes the Winchester Mystery House would have been: rooms that lead to everywhere, to desires and fantasies that you never even knew you had, and that you’ll never admit to the following morning. Rasputin is more than a strip-club and more than a Moscow institution: It’s the apex of a flesh-network, involving scores of smaller, lesser strip clubs that feed into Rasputin like minor league teams feeding into the major league club. For nearly five years, from 2002 to 2007, my newspaper’s office was located in the back of Rasputin’s sex club; when we’d order business lunches during work hours, strippers in see-through negligees and glass high-heels brought Borsch and Kotleti to our offices for a mere 40 rubles ($1.50), leading one American former editor to spasm in dangerous palpitation sweats.

Point being: These are good friends to have, but bad enemies to make.

So when my publisher told me last night, “As far as I see it, the Exile‘s debts are yours as well, Mark,” my little saga took a very unforeseen and unpleasant turn.

And then today the media circus finally erupted here in Moscow. What set it off was an article about the Exile‘s closing in today’s Der Spiegel, which was translated into Russian for the online media. Throughout the course of the day today, I’ve been deluged with phone calls and e-mails from the Russian media, who have already begun posting articles misquoting me in that special way that only the Russian media can manage.

Edward Limonov, the politician-columnist whose articles are at least partly responsible for attracting the authorities’ attention, told me that he too was posting an article on www.grani.ru about the government attack on the Exile, and he told me that his opposition partner Garry Kasparov had called him today to ask him about us.

I’d tell you more, vaguely related stuff, like about how the northern city of Syktykvar just had all of the sand stolen from its makeshift “beach” on its river, and the prosecutor is looking for the sand-rustlers, who are believed to be operating a barge on the river … but I have to run to a meeting with my remaining employees, to give them the final death notice, and they keep ringing me as I write this.

Later tonight, FHM magazine is holding a party on the top floor of a new Moscow skyscraper. Since everyone is treating me as if I’m dripping in polonium, I plan to attend, to shake hands with everyone I can, take photos with them, thank them for their crucial support. You see, ever since I was a kid I vowed that if I wound up paralyzed and in a wheelchair, that I’d have my nurse wheel me up to restaurant windows and leave me there to drool, to make the ambulatory types squirm.

My current situation isn’t exactly stick-on-the-forehead dire, but it’s close enough. I’m going to see how people try to squirm from me tonight. Try to squirm, and not get away with it.

* * *

HAPPY RUSSIA DAY!

June 12, 2008

Today is “Russia Day.” It’s the official holiday when Russians celebrate their independence—from their own empire. On June 12, 1990, the Russian Republic’s parliament passed a resolution declaring “sovereignty” from the USSR, paving the way for Russia to “free” itself from the 14 other republics it had spent centuries conquering. It would be like Mexico celebrating February 2, 1848—the day Santa Anna was forced to sign away California and the entire Southwest to the gringos—as “Mexico Day.”

Which may explain why Russia’s state-run RIA Novosti grimly announced, “Unfortunately, the name of this holiday disorients the people completely.”

Whatever. Today’s a holiday, so I should relax and enjoy the party and forget about the fact that I’m under attack. For the celebration here in Moscow, the Kremlin is flying in none other than former French president Jacques Chirac, so that Medvedev can pin a medal on the old whore’s saggy man-boobs, to honor his “contribution to promoting Russian culture“—exactly what my paper is accused of not doing properly enough. I guess you don’t get Kremlin medals when you headline your paper that you “dare to fart in Russia’s face.” But that doesn’t explain why Chirac would agree to make such a complete ass out of himself on the world stage. It would be like flying to Riyadh so the king could honor you with a “Female Driving Instructor of the Year” sash.

Perhaps Chirac came just for the after-party. Now that Medvedev is the new tsar, he has the authority to hire his favorite band to play at his Red Square Russia Day party—and wouldn’t you know, he chose none other than Uriah Heep to rock the Kremlin walls down. If you’ve never heard of Uriah Heep—and 99 percent of you haven’t—you’re missing out: They’re a real-life Spinal Tap classic-rock outfit that packs stadiums from Smolensk to Kamchatka, even though they couldn’t land a gig on open-mike night in a Tuscaloosa saloon. True to their Spinal Tap calling, Uriah Heep pulled out of their Red Square gig today at the last minute, fucking up Medvedev’s classic rawk party, which their website blames on the “tour promoters [sic] complete lack of adherence to contractual stipulations.” I can imagine how the Heep fell out with their promoters: “You call this a sandwich, huh, Vladimir? I don’t want this! Because, look, you have to fold it like this, and then … no, it’s a fucking joke, really. I can’t do this, I won’t go to fucking Belarus if I can’t get a proper fucking sandwich.”

Heep or no Heep, there will be no rain on Medvedev’s parade, as the air force scrambled 10 rickety Soviet-era planes to disperse the clouds. And they’ve called up 6,500 police, including 550 OMON paramilitary goons, to make sure to make sure no one bum-rushes the stage when the vertically challenged leader makes his appearance. For a sample of the OMON at work and play, watch this video cut by the Exile‘s coeditor Yasha Levine:

For me, it’s a good thing there’s a holiday break today, because yesterday, my now-dead newspaper, the Exile, became the cause-célèbre story in the Russian opposition media. The attack on my paper got converted into a bag full of burning shit and tossed on the Kremlin doorstep to embarrass Russia’s president Dmitry Medvedev on the very same day that he gave the keynote address at the World Russian Media Conference in Moscow, where he pledged to “ensure media freedom and respect for human rights.” Exiled oligarch Vladimir Gusinsky‘s popular online portal, newsru.com, juxtaposed Medvedev’s speech with the closing of the Exile: “Medvedev made his announcement about supporting the press in the background of the incredible story about the Moscow-based American newspaper the Exile, which is being threatened by officials with censorship due to the newspaper’s alleged extremism.”

Eduard Limonov, the radical opposition leader-slash-celebrity, told leading opposition radio station Ekho Moskvy (the same station Condi Rice makes a point of visiting whenever she flies into Moscow for her annual missile defense hustle) that the attack on the Exile is really an attack on Eduard Limonov—and that it’s all about him. This isn’t just a case of Limonov pulling a PR stunt: On Monday, a dozen young members of Limonov’s banned National Bolshevik Party stormed the Russian government’s Railways Ministry building in central Moscow, seizing offices, smashing open windows, and unfurling antigovernment banners in solidarity with striking railway workers. It ended as it always does: The dozen activists were hauled off, and no one knows what their fate will be.

Four years ago, a similar stunt by Limonov’s National Bolsheviks led to the arrest of nearly 50 activists, a spectacular trial, and the Russian Supreme Court banning Limonov’s party.

It’s a tough and dangerous job out here in opposition to the Kremlin. Publicity is the most prized currency: It’s generally considered your best defense against a bad fate, and since most opponents are of the public-transport-riding socioeconomic class, it’s really the only defense. Everyone knows that there’s a roughly zero percent chance of winning against The Man, but losing comes in many different forms—from glorious standoff to extinction. That’s why the opposition needs to divvy up the publicity—and the exposure—as widely as possible.

And right now, I’m part of the developing story, and I’m getting sucked into the bigger battle. Two opposition media outlets, radio station Govorit Moskva and magazine/portal New Times, want to interview me early next week about theExile in the context of a wave of audits that are sweeping the Russian provinces. (My paper’s audit is still the first one ever for a Moscow-based newspaper.) New Times made international headlines last December when one of its investigative reporters, young über-babe Natalia Morar, was expelled from Russia and labeled a threat to state security. I met Morar for lunch with another American journalist about a month before she was expelled, and I left that meeting deeply annoyed by her Tracy Flick–like ambitiousness, as well as her clear lack of sexual interest in me. But after her expulsion, well, any criticism just seems vulgar and cheap. Meanwhile, Govorit Moskva called me and asked if they could put me on a live debate next week across from the chairman of the Russian Duma’s Committee on Political Information, Valery Komissarov.

I dunno, folks! I mean, should I? Should I start wearing a helmet? Or the flack jacket that’s still in our office, a gift from the first war in Chechnya? Is there a lawyer in the house who can e-mail me a little advice on this? Or would a rabbi be more appropriate at this point?

I have no idea where all this is leading, and neither does anyone else. In the meantime, I’ve just downloaded Black Sabbath’s Paranoia album, because Black Sabbath is apparently one of Dmitry Medvedev’s favorite bands. When I listen to “War Pigs,” I’m brought back to my bong-stenched dirthead youth in the San Jose suburbs—and for the first time, those dirthead days don’t seem so bad. I wonder, what does Dmitry Medvedev think of when he listens to “War Pigs”?

* * *

PAYING THE KREMLIN

June 16, 2008

Today’s lesson is that even after the Russian authorities have destroyed you, they’re not satisfied; they still have to humiliate you in little ways. And even then, they’re annoyed with you.

I went to the Russian state bank and paid the 500 ruble ($22) fine to the government for all of the little administrative screw-ups in my now-defunct newspaper, the Exile, which was effectively shut down over a week ago by the authorities. The fines I paid today are completely separate from the alleged “extremism” or “drug-promotion” or “mockery of Russian traditions” that our paper is currently being investigated for. We were indeed guilty of all sorts of little errors that starched ‘n professional media types would never flub—we forgot to put in our new address, forgot to use Cyrillic fonts in the masthead, forgot to print our license number—but more than anything, we forgot to show the appropriate enthusiasm for President Medvedev, an enthusiasm which should be calibrated just a respectable notch or so below his mentor, the slightly-less-vertically-challenged Vladimir Putin.

Now that the Russian government has successfully frightened our paper out of existence, they can start working on their new spin: this had nothing to do with censorship, and everything to do with making sure that we got our address properly written down. Sort of like how Third World despots shut down opposition media outlets for “tax evasion,” rather than opposing the local Boss.

It was a strangely humiliating experience, standing in line for half an hour in a crowded, sweaty Sberbank outlet, waiting to pay the government for the pleasure of losing my newspaper of 11 years. Two meat-heads to my left almost got into a free-for-all fight over who was ahead of whom in line—cutting is a Russian tradition, and threats of violence are all part of the line-cutting ritual.

When the teller took my passport and the ticket for the fine, she froze for about 2 long minutes, clutching my US passport like it was a live wire. What’s an American doing paying a fine to the Russian government? Doesn’t Russia only levy unnecessary fines on its own citizens? What if the world found out about this?! Clearly she didn’t relish the potential scandal that this might cause. She called over her manager, and the two of them conferred for about 10 minutes, discussing whether or not accepting an American payment for a fine could turn into what Russians call “an international incident.”

My (now former) sales director Zalina tapped on the teller window and told them that they had to let me pay, that my American passport was valid and named on the ticket for the fine, and that they shouldn’t worry, it was unlikely to spark World War Four. A Gary Powers incident at most, but nothing more.

War or no war, according to a few journalists who interviewed me today, the ministry officials are starting to get seriously annoyed with me. One foreign correspondent told me that the press spokesman for the Federal Agency for Media and Communications (as it’s now called) snapped in annoyance at his questions, claiming that the audit was “completely normal,” and that I had apparently lied about it being an “unplanned audit.” So I emailed a scan of the ministry’s official notification of their audit to the reporter, on which it reads in plain Russian “Unplanned Audit.” He wrote me back, “Do they think we’re fucking morons?”

A better question would be, “Do they fucking care?”

Another Western reporter told me that when he called the ministry spokesman, that the man “exploded” and barked, “Why is everyone calling me about theExile?!” As the reporter explained, “It sounded like my call was about the 15th call he’d taken in the last hour, and he couldn’t take anymore. It was kind of funny.”

Perhaps. But pissed-off Russian bureaucrats don’t have a bygones-be-bygones habit of popping open a Miller with people who piss them off at the end of the day. When they get angry, they have a nasty habit of…actually I’d rather not think about that right now. They already made me pay this humiliating fine for a paper that they’d taken away from me.

Tomorrow I’m to be interviewed in the anti-Kremlin media outlet New Times. Meanwhile, the story is finally getting delayed coverage in the English-language print media. I’m not sure if that’s buying me some time here, or just pissing off the ministry officials even more.

* * *

RUSSIAN MEDIA CRACKDOWN GAINING ATTENTION

June 18, 2008

Today’s Wall Street Journal brings word of a troubling blow against press freedom in Russia: “An English-language newspaper in Moscow famed for lampooning Russian and Western officialdom has shut down after it fell under the scrutiny of the government for its raucous content. The demise of Moscow’s Exile newspaper is the latest sign of the homogenization of the press within Russia, where an official crackdown on dissent has led to the self-censorship of many publications.” Of course, that won’t come as news to you if you’ve been following Exile editor Mark Ames‘ dispatches from the front. If you’ve missed them, you can read them here.

* * *

WHEN A FASCIST CALLS YOU AN EXTREMIST, YOU KNOW THINGS ARE BAD

As this article is going online, I’ve either made it out of Moscow to London, or I’m stuck in a border-guard interrogation room in Sheremetyevo International Airport. Nothing will surprise me anymore. Two weeks ago, the Russian government closed down my newspaper, the Exile. And then last Thursday, during a live Moscow radio show on which I was a guest, a Putinjugend-turned-Duma deputy accused me and my newspaper of “extremism.” That might be a badge of honor for a journalist anywhere else in the world but Russia, where the word “extremist” has serious legal and extralegal implications. During Putin’s reign, the meaning of the word “extremist” was expanded to include anyone or anything who upset the Kremlin—particularly liberal critics such as the Washington-based think-tank analyst Andrei Piontovsky, who last year faced criminal charges over two books that are critical of Putin, on the grounds that they are “extremist.”

Thursday was a bad day from the minute I woke up—it started with a rude hangover, following the Exile‘s staff funeral party. Thanks to the persuasive skills of our sales girls Zalina and Lena, we managed to cop an all-expenses-paid feast at a striptease club/bordello named Violete, located directly across the river from the Kremlin. It was our way of saying “fuck you” to The Man, heavy emphasis on the “fuck.” The party rolled on from Wednesday night late into Thursday morning—and it was a very long night indeed, abandoning the slow cocktails for entire bottles of “Platinum” Russian vodka, drowning ourselves in long lugubrious toasts, then disappearing into the dark pole-dance room, where flocks of naked girls vastly outnumbering the males pile on top of you like you’re Axl Rose, and then one of them leads you farther back into Violete’s catacombs, into one of the lap dance “cabinets” for a little “extremist” activity: a 15-minute reenactment of the Mongol horde’s plunder of ancient Rus, with me as Genghis Khan and Nastya playing the war booty. The Exiledied that night just as it was born: deep in sin.

And then, in just a matter of hours, I went from Violete to hangover-nausea to the awful news that at 10 p.m. Thursday, I’d be squaring off on a live radio show against one of the most menacing creatures in the new Putin generation: Robert Schlegel, a 23-year-old ginger-haired Kremlin tool whom a girlfriend of mine described as “looking like one of those perverts from a Todd Solondz film.”

While it’s true that Schlegel has a kind of hairless-scrotum twinkie-porn look about him, when you put that into the context of his frightening “Heil Putin” politics, and the fact that he comes from Volga German stock, you start to suspect that Schlegel isn’t entirely human the way you and I are, but is rather some kind of genetically engineered Boys From Brazil product, created so that he might one day serve a cruel and scary tyrant.

And Schlegel’s aggressively enthusiastic gig has worked out pretty damn well so far: In just a few short years, he’s risen from spokesman for the Kremlin’s young goon squad organization, Nashi, which was created to harass and frighten Putin’s critics (including even Britain’s ambassador to Russia), to taking a seat this year in the state Duma, where he promptly went to work pushing through a bill that would strangle the already strangled Russian media.

When I found out that I’d be debating Schlegel, my sweat glands started to swell up and produced a ghastly odor that I can only trace to my grandfather’s ancestors from Fez. So I did my equivalent of Tooter calling for Mr. Wizard, which in my case meant calling up Eduard Limonov, the radical opposition leader whom I was sure would have an opinion on Schlegel.

“This Schlegel is just a schmuck,” Limonov said. “He’s rather intelligent, young, but very arrogant, and really he’s a fascist. And you should tell him that, too. Really, tell him that he’s a fascist schmuck, that he’s a traitor to the motherland, because he’s really a disgusting kid.”

Limonov’s party members have been violently attacked on more than one occasion by baseball-bat-wielding Nashi youths while Schlegel was acting as their spokesman, so his contempt is easy to understand. But still, an American accusing a high-profile Duma deputy of treason and fascism can be a very expensive affair these days—in more ways than one.

I arrived late at Govorit Moskva’s studio, housed in a rundown building just a few hundred yards from the Violete striptease club. I had to run up the stairwell to make it in time. My head was pounding, and I stank up the entire room with fear-sweat as I took the headphones. Luckily, Schlegel wasn’t in the studio. Russia’s Duma deputies are currently touring the provinces for a kind of “get to know the people whom you’re oppressing” ritual they do every so often, meaning Schlegel was phoning in for the show—and I wouldn’t have to look at him.

“How long will the interview last?” I asked the radio host as I put on my headphones.

“An hour, of course,” he said.

I sank in my seat. My Russian is decent enough under the right circumstances, but in the throes of a hangover, at 10 p.m., debating a fascist hothead Duma deputy with my tongue hogtied was terrifying as hell. The only question now was how to limit the damage, and make it through without completely shaming my ancestors, my country, and my profession.

Right from the start, Schlegel was extremely confident, lamenting the fact that his censorship bill, which he rammed through the Duma this past April almost unopposed on the first reading, was then rudely smacked down by President Dmitry Medvedev. Schlegel admitted with a wry laugh that indeed he had been brought to heel by the new president, and that there was no point in reintroducing the law. But he didn’t show much respect for Medvedev’s moderation, terming the veto “his opinion.”

Then it was my turn. As I explained what happened to the Exile, how the ministry inspectors frightened our investors away, leading to the newspaper’s collapse, Schlegel dismissively countered that there was nothing unusual or frightening about a Russian ministry audit of a newspaper’s article. But when I explained to him that such government audits only take place in Third World dictatorships and not in serious countries, his tone changed, and his fangs started to show.

“The Russian media is completely free,” he claimed. “Our television stations express all the opinions of the people.”

How do you respond to that? I told him that he lived in some strange parallel world separate from the world everyone else in Russia lives in; his world was some kind of formalistic fantasy land where all of Russia ran a law-abiding state; the world the rest of us saw was one in which people hid from Russia’s cruel and arbitrary powers, so when a media outlet like the Exile gets fingered, people understandably run. Schlegel didn’t take kindly to it.

When I started to talk about the shameful self-censorship that went on in the American media in the lead-up to the Iraq war, and the disastrous consequences that followed, Schlegel loudly cut me off: “The American media was right to support the invasion of Iraq, because the American people supported that war. Of course the American media should back the president!”

“But the only reason that the American people supported the war was because the media duped them! They didn’t do what they were supposed to do!” I stammered.

“No, Bush was right to invade Iraq!” Schlegel yelled. “I absolutely support his reasons for invading, and I believe the American media did the right thing in supporting the war, because the American people supported this war.”

And that’s when the young Russian Duma deputy turned his fangs on me: “I understand what type of person you are now, Mark, after listening to you and hearing about your newspaper, the Exile, on this radio program. It’s very clear to me now that you are anextremist, and your newspaper isextremist. I have never read your newspaper, but I don’t need to now because I already have you figured out. You’re an extremist. It’s all completely clear to me now.”

It was the longest hour of my life, an infuriating and exhausting experience that left me feeling corrupted. I went home late that night thinking what Schopenhauer had said about this world being hell, where men are divided into torturing devils and the condemned. Schlegel was born to be a torturing devil if there ever was one.

When I got back to my apartment, I received an e-mail notifying me that the New York–based Committee to Protect Journalists had issued an alert on my defunct newspaper’s behalf. I felt—and still feel—oddly grateful to them for throwing their weight behind our story, but I understand that it won’t do much to help me now that I’ve been labeled an “extremist” by a Russian Duma deputy; nor will it hurt Schlegel, who can say whatever he wants.

About five hours from now, as I’m sending this off to Radar, I’ll be on my way to Sheremetyevo Airport. That vacation I’ve been talking about is now long overdue.

##

Would you like to know more? Read about the Wikileaks cables on The eXile and the Kremlin crackdown.

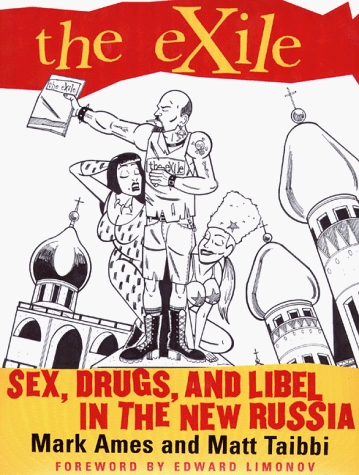

Buy The eXile: Sex, Drugs and Libel in the New Russia co-authored by Mark Ames and Matt Taibbi (Grove).

Click the cover & buy the book!

Read more: andrei piontovsky, axl rose, eduard limonov, extremism, moscow, putin, radar, robert schlegel, Russia, Schopenhauer, sheremetyevo airport, strip club, the exile, Mark Ames, eXile Classic, Russia

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

10 Comments

Add your own1. Пятое Yправление | May 26th, 2011 at 12:41 am

И ваша точка? Мы имеем долгую память. Никогда не играть против дома.

2. Thomzas | May 26th, 2011 at 3:27 am

И ваша точка? Мы имеем долгую память. Никогда не играть против дома.

Seems to translate as

“And your point? We have a long memory. Never play against the house.”

Creepy

3. somatzu | May 26th, 2011 at 8:06 am

Hmm… maybe the poster meant to say “duma”

4. Пятое Yправление | May 26th, 2011 at 10:26 am

The ‘house’. The duma has never counted for anything.

Мы управляем горизонтальной. Мы контролируем вертикальной. Мы контролируем IKEA, папства римской, и Wal-Mart.

5. Korman643 | May 26th, 2011 at 11:39 am

Мы управляем горизонтальной. Мы контролируем вертикальной. Мы контролируем IKEA, папства римской, и Wal-Mart.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wur16G_88VA

Maybe yes, maybe not.

6. Пол | May 26th, 2011 at 9:10 pm

Я тот, как вы ему, как вы мне, и мы все вместе.

Посмотрите, как они бегут, как свиньи из пушки, видеть, как они летят.

Я плачу.

7. emiliano | May 28th, 2011 at 3:42 pm

But still, you couldn’t publish the old eXile stuff anywhere except Sealand nowadays, so what happened with your debts to that whorehouse pimp?

8. DarkCloud | June 23rd, 2011 at 1:13 am

Please introduce me to Zalina.

9. BlackRussian | July 7th, 2011 at 3:57 am

So sad you tend to demonize the guys. I know you were scared and it was very personal to you but still… And yes Schliegel is a jingo but… he initiated laws that forced gambling out of into special zones, introduced strict penalties for retail outlets that sell alcohol and tobacco to kids and abolished visas for discriminated ethnically Russian citizens of Baltic republics (the so called non-citizens). All this makes him a nationalist which is not bad in the present circumstances. Given of course he is “brought to heel” every once in a while:)

10. BlackRussian | July 7th, 2011 at 4:07 am

Indeed try to do the same trick with public claims you are going to fart in the face of a nation and piss in its presidents mouth and with this sort of humor you won’t last long anywhere as a media outlet, let alone the “Most democratic of all democracies”, the US.

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed