This was first published as a Radio War Nerd subscriber newsletter on May 21, 2021. But with the total collapse of the US-backed Kabul regime, it’s even more relevant now to ask: What was the strategy?

Was there ever a plan there?

So what was supposed to happen back in October 2001, when the US forces invaded? I’ve been going through the papers of record, the NYT and WaPo, to see what the official line was, year by year. The first years of an occupation are the most important, so I’ve focused on the first five full years of US occupation, 2002-2007. You can find a good timeline of these years here, but it’s much harder to find any trace of a plan.

The US invaded both Afghanistan (October 2001) and Iraq (March 2003), but not all invasions are equal. For the DC elite, Iraq was a war of choice, while Afghanistan was just a grim preliminary chore. They had to invade Afghanistan quickly after the WTC attacks, because it was all over the news that Al Qaeda had its HQ there and the voters were angry. Public support for invading Afghanistan was higher than for invading Iraq.

But those in the know, in the three-letter agencies and the DC elite, knew Afghanistan was hopeless. They knew this because the Taliban, officially the enemy in Afghanistan, was sponsored and protected by the Pakistani armed forces. And Pakistan was never going to hand over Osama bin Laden or Mullah Omar, leader of the Taliban, to the Americans. The Pakistani intel elite, one of the scariest, murkiest groups in the world, cherished its pet jihadis as its one reliable weapon against the hated Indians. It was never going to help destroy them, or even cooperate in any serious pruning operation.

A decade after the US invaded with the supposed help of Pakistan, Osama was found in a big compound inside Pakistan, a few hundred meters from a Pakistani military. At that point even us rubes knew that the Pakistani government had never intended to betray its Taliban allies. (Note: “Taliban” here means the “Afghan Taliban,” as opposed to the later “Pakistani Taliban,” which the Pakistani gov’t, or at least some elements of that gov’t, really does dislike. Like I said, it’s murky.)

Nobody at the CIA or the 16 other US intel agencies really thought the Pakistani gov’t would give up their friends. And nobody in DC really thought that Afghans, as they imagined Afghans, would welcome American troops. So from the start, this was the poor stepchild invasion, while Iraq was coddled.

They had high hopes for Iraq. Iraqis, in the neocon dream, were really proto-Americans, just waiting for a Shock and Awe Apocalypse to free their inner Republican. Afghans, OTOH, were scary and alien. Brave, yes; remember all those Reagan-era movies on the glorious Afghan resistance?

Maybe too brave, in fact. The DC elite had heard that cliché about “Afghanistan, Graveyard of Empires” and believed it. Who wants to invade a dirt-poor country full of brave warriors who don’t seem like good candidates for transformation into suburban Americans?

The DC blob had no real hopes or plans for Afghanistan — and the stories from NYT and WaPo reflect that. These stories use several different models, which I’ll try to characterize here. They overlap, over the years 2002-2007, but they’re not in any strict chronological order. It’s more that those whose unlucky job it was to explain the invasion used whichever model retained a figleaf of plausibility at the time.

1. Revenge on a Budget

As Mark Ames said long ago, people in the US in the months after the WTC attacks acted as if the Martians had invaded. There was shock, rage, and an overpowering urge to whack somebody as soon and as hard as possible.

“Al Qaeda” and “Osama bin Laden” were the names given to this enemy, and “Afghanistan” was the place he’d hidden out to plan the attacks. So Afghanistan became a target. Not, at this stage, a project. It’s an important distinction. Iraq was always a project, but Afghanistan was just a target.

The New York Times’s series “A Nation Challenged” (2001/2) is typical of this first wave of Afghan stories. The challenged nation is America, and invading Afghanistan is just a part of America’s response to that challenge.

By making Afghanistan a “challenge,” the US played out its role as punitive invader.

Some people claim that was Osama’s plan all along: “Al Qaeda planned it that way! They knew the US would overreact and bankrupt itself in an endless ‘war on terror’!” Eeeh, I dunno. That’s how it played out, definitely, but TBH I don’t know if Al Qaeda’s leaders planned 9/11 that way or just wanted to hit the US as hard as possible. There was plenty of reason for Salafi Muslims to hate the US. Maybe they saw 9/11 as simple justice.

But if Osama hadn’t planned it, he was sure glad at the way it was turning out. In 2004 he gloated that he had managed to “bleed America into bankruptcy.” Someone in DoD circles should’ve taken that claim seriously. After all, Osama knew what he was talking about when it came to money. He came from big money and had done his bit in the Soviet Afghan War, which supposedly bankrupted the USSR.

The Afghan War was not, in fact, what doomed the USSR. But that cliché was almost universally believed, and with particular intensity in the DC Blob — so you might think US intel would at least have considered the possibility that this was Al Qaeda’s plan.

Here’s a typical story from the New York Times’ ‘Challenged’ series, October 8 2001:

“[Mr. Rumsfeld] said the goals of the military operation were to punish the Taliban for ‘harboring terrorists,’ to ‘acquire intelligence’ that will help future operations against Al Qaeda and to weaken the Taliban so severely that they will not be able to withstand an opposition assault.

“Another goal, Mr. Rumsfeld said, is to provide relief aid ‘to Afghans suffering truly oppressive living conditions under the Taliban regime.'”

Helping Afghans barely gets a mention, as “another goal.” That was a low priority at this stage.

You never get much sense of the Afghans themselves in these early stories. They’re a vague, hostile presence, an unknowable barbarian people. This was very different from the way Anglo media portrayed Iraqis, who were seen as lusting for democracy and commerce.

Like I said, Iraq was the real prize, Afghanistan was a chore that had to be done first. The reason was simple: Osama’s base (Qaeda) was in Afghanistan and every news consumer knew it. So the place had to be cleaned out, as quickly as possible, so the juggernaut could move on to Iraq.

This made for a quick, dirty, low-cost Rumsfeld plan for Afghanistan: lots of air strikes, low numbers of troops, mostly various “special forces” units, and little interest in the whole hearts-and-minds side of war. That was saved for Iraq. Afghans were supposed to get out of the way while the hunt for “terrorists” went on, mostly in the Pashtun southeast.

The initial campaign was very quick. One month after 9/11, the US and 40 reluctant allies started bombing.

It would be wrong to call this stage an occupation. Most of the countryside was untouched except by bombing raids. The rural patriarchy in the south, which was the Taliban, melted back into the villages after the fall of Mazar-i-Sharif. Some had been killed but even they had brothers and cousins who were happy to replace them when the time came. These guys were not typical Afghans, but then neither were the minorities and city folk who wanted change. And this first phase of the occupation did nothing to placate either part of the population.

The one cliché about Afghans we all knew was that “they hate foreigners.” Nobody asked Afghans about that generalization. And as it turned out, it was wrong.

Many Afghans were sick of the Taliban, who were mostly hick bigots, and were glad to see them overthrown. City people, educated women, and minority groups like the Hazara were especially happy to see the grimly enforced Pashtunwallah of the Taliban smashed, but even in some rural areas there was relief and hope that some money would flow in. As the NYTimes later wrote,

“The perception was that Afghans hated foreigners and that the Iraqis would welcome us,” said James Dobbins, the administration’s former special envoy for Afghanistan. “The reverse turned out to be the case.”’

Rumsfeld’s plan, heavy on air strikes and low on intelligence, wiped out that initial goodwill. “Air strike hits wedding party” became a standard headline, because from orbiting F-16s, a wedding can look a lot like an insurgent gathering. Or maybe any gathering was hostile by definition, in the years after 9/11/. The point was to hit somebody, never mind who.

A few reporters were recording the wedding attacks, but the light-and-quick strategy went on, and the “mistaken” air strikes with it.

2. Get ’er Done

No one in DC was worried about these mistakes. The point was to get Afghanistan done so they could move on to Iraq.

A year after invading, the NYT reported the fact that US troops just might have to stay a little longer as a surprise:

“October 13 2002

“A YEAR after the United States attacked Afghanistan, more than 9,000 American forces remain inside the country, hunting down remnants of Al Qaeda, building roads and schools, and struggling to adjust from a combat role to what looks more like a nation-building mission.

“Plenty of problems persist. Osama bin Laden, the Qaeda leader, may or may not still be alive, and Mullah Mohammed Omar, the former head of the Taliban, remains at large. Efforts to train a new multi-ethnic Afghan national army that would bolster the central government’s authority in lawless regions of the country have taken longer than expected. Regional warlords are feuding, posing new challenges to President Hamid Karzai’s government. Aid has been slow to reach many parts of the country.

“All this has led American commanders to acknowledge that United States troops will remain in Afghanistan at least another year and, more likely, much longer than that.”

The saddest thing about this paragraph is that it could be a 2020 story. “Much longer” turned out to be an understatement.

But back in 2002, the collateral killings were seen as blips, annoying but minor, in the Brain Trust’s big plan. By the spring of 2003, Rumsfeld announced that combat in Afghanistan was over:

“Mr. Rumsfeld said it had taken longer for a smaller force to root out elusive Qaeda terrorists than for the military to trounce the Iraqi armed forces, but he suggested that Afghanistan could be a laboratory for Iraqi reconstruction efforts. This is Mr. Rumsfeld’s third trip to Afghanistan since Sept. 11, 2001, and he praised the progress he had witnessed.”

3. Afghanistan is Like Kosovo, Sorta

Analogies, the dumber the better, were popular in these early days of the war. Michael Ignatieff, mercifully forgotten today, was a big name in those unlucky times. He had hope for Afghanistan under American occupation, based on its well-known similarities to…Bosnia. Yeah, that’s Afghanistan, the Bosnia of Central Asia. Here is Ignatieff writing in July, 2002:

“It will take years before the national government in Kabul accumulates enough revenue, international prestige and armed force to draw power away from the warlords. But Bosnia shows it can be done. Six years after the war, the Muslim, Croat and Serb armies are rusting away, the old warlords have gone into politics or business and a small national army of Bosnia is slowly coming into existence. The problem in Bosnia is corruption, and that is a better problem to have than war.”

This nonsense was taken seriously in part because Americans were hearing similar nonsense about Iraq. For example, Ken Adelman, who could give Doug Feith a running for “dumbest guy in the world,” actually wrote this in the pages of the Washington Post:

“I believe demolishing [Saddam] Hussein’s military power and liberating Iraq would be a cakewalk. Let me give simple, responsible reasons: (1) It was a cakewalk last time; (2) they’ve become much weaker; (3) we’ve become much stronger; and (4) now we’re playing for keeps.”

Hear the playground woofing, “now we’re playing for keeps”? That stuff was how America’s elite talked in the Millennial ear. You almost expect little Ken to add the slogan from Jaws 4: The Revenge — “This time it’s personal.”

As the US was gearing up for the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the NYT/WaPo stories about Afghanistan fill with talk about “multiple” theaters of war and the hope that NATO proxies will soon take over in Afghanistan. Like this:

“In his article today, Ambassador Burns praised NATO for showing ‘it is serious about a transformation that has been in the works for almost two years.’

“General Jones noted that the alliance was moving from the ’20th century defensive bipolar world’ into a multipolar world requiring a flexible and rapid response to a myriad of threats. He called it ‘a signal moment in the history of the alliance.’”

4. We Were Always Here for the Long Term

In March 2003 the US invaded Iraq. This invasion was far bigger, better-planned, and much dearer to the hearts of Cheney’s buddies than Afghanistan had ever been.

It was so much more important to the DC elite that long before US troops actually entered Iraq, the US was diverting people and money there from Afghanistan. This was despite the failure of all aspects of the initial US plan in Afghanistan

find and kill bin Laden, Zawahiri, and the rest of the Al Qaeda elite

put Taliban leader Mullah Omar on trial

crush the Taliban in the countryside

Osama wasn’t caught and killed until 2011. Mullah Omar has never been found. Zawahiri continued broadcasting his cave-side chats for years and may still be alive somewhere, watching his blood-sugar count and sending legalistic quibbles to jihadi whippersnappers.

“Ramadan travel rules during Jihad? You young punks don’t know a thing about…”

5. Afghanistan is Like 1946 Germany, Sorta Kinda

What, then, was the US still doing in Afghanistan? No one seemed to know. And careers would be ruined if “we” left the place after failing to catch a single one of the WTC planners. So a new mission was devised. “We” were going to transform Afghanistan the way the US had transformed Europe after WW 2.

Yes indeed, there was a “Marshall Plan” for Afghanistan. George W. Bush announced it in 2002, and the NYT obliged by ribbing the boss a little about his sudden U-turn toward “nation-building,” then added this ponderous litotes:

“The parallel for Afghanistan that Mr. Bush drew with the Marshall Plan is both apt and inexact.”

Welp, they were half right. The NYT concluded,

“Mr. Bush said recently, ‘We fight against poverty because hope is an answer to terror.’ This is true, and suggests that the Bush administration is reshaping its view of nation-building. Afghanistan will be its first test.”

Those of you young enough not to have lived through eight years of GWB, take a good long look at Bush’s line: “We fight against poverty because hope is an answer to terror.” That kind of pious gibberish, with its wildly unmoored jump from “poverty” — a real fact about Afghanistan — to “hope,” an intentionally meaningless term, and “terror,” an even crazier noun which was supposed to explain all resistance to the Cheney Plan — that was the “civil” discourse squishy liberals revere GWB for.

Like a lot of GWB’s blather, it’s hard to come up with a translation. The closest you can get is roughly: “We’ll throw some money at Afghanistan too, but let’s get on with Iraq.”

So in this stage, the plan became “nation-building,” long after the moment when any such project could have worked.

6. Ayn Randistan

This was the moment when America’s devout belief in the free market ran up against reality in Afghanistan. You can’t exaggerate the rigid faith in The Market which possessed the US elite around the Millennium. The Market would solve all problems; that was obvious to everyone.

Thomas Friedman, high priest of elite stupidity, had a famous epiphany: No two countries with McDonald’s franchises had ever gone to war. Or, he suggested, ever could go to war. Bomb Kabul with prefab golden arches and watch peace’n’prosperity break out.

The trouble was — well, first of all, “the free market” doesn’t exist and never has. Quoting from the WaPo’s Afghanistan Papers:

“In developing countries, ‘the idea that there are perfectly functioning markets without subsidies is pure fiction, fantasy,’ Rubin, a New York University professor and leading academic on Afghanistan, told government interviewers. ‘Every late-developing country happened by government picking winners.’“

There were trained people ready to transform Afghanistan. But they were socialists — commies, in the US view.

“There was a solid pool of educated, enthusiastic, honest Afghans with bureaucratic experience. But they wanted to recreate the socialist society of Afghanistan’s ‘Golden Era’ of the mid-20th century.

“…several U.S. officials told government interviewers it quickly became apparent that people who would make up the Afghan ruling class were too set in their ways to change.”

“’These people went to the communist school,” said Finn, the former ambassador. A common Afghan fear, he recalled, was ‘if you allow capitalism, these private companies would come in and make profit.‘”

As the US occupation of Iraq went from bad to worse around 2005, there was even less energy in DC to worry about the pattern of stagnation in Afghanistan.

By 2007, the NYT was already doing post-mortems with titles like “Afghanistan: How A ‘Good’ War Went Bad,” detailing the complete failure of the ludicrous “Afghan Marshall Plan”:

“When it came to reconstruction, big goals were announced, big projects identified. Yet in the year Mr. Bush promised a ‘Marshall Plan’ for Afghanistan, the country received less assistance per capita than did post-conflict Bosnia and Kosovo, or even desperately poor Haiti, according to a RAND Corporation study. Washington has spent an average of $3.4 billion a year reconstructing Afghanistan, less than half of what it has spent in Iraq, according to the Congressional Research Service.”

All remaining investment in Afghanistan went to the war, not development.

“…[A] senior American commander said that even as the military force grew…he was surprised to discover that ‘I could count on the fingers of one or two hands the number of U.S. government agricultural experts’ in Afghanistan, where 80 percent of the economy is agricultural. A $300 million project authorized by Congress for small businesses was never financed.”

7. Dark Matter in Crates off a C-130

Maybe that money is the real story here. Because there’s something missing. Why did this mess go on so long when it never had anything resembling a reasonable plan? It makes no sense.

It makes no sense as a military operation, as nation-building, or as Imperial expansion. There’s something skewing the numbers, like the Dark Matter that makes cosmologists drink, turn religious, or just sob in their offices at night.

In the Physics of the Afghan occupation, I suspect that that Dark Matter consists of big ol’ globs of cash. Maybe the waste of two trillion dollars was the point.

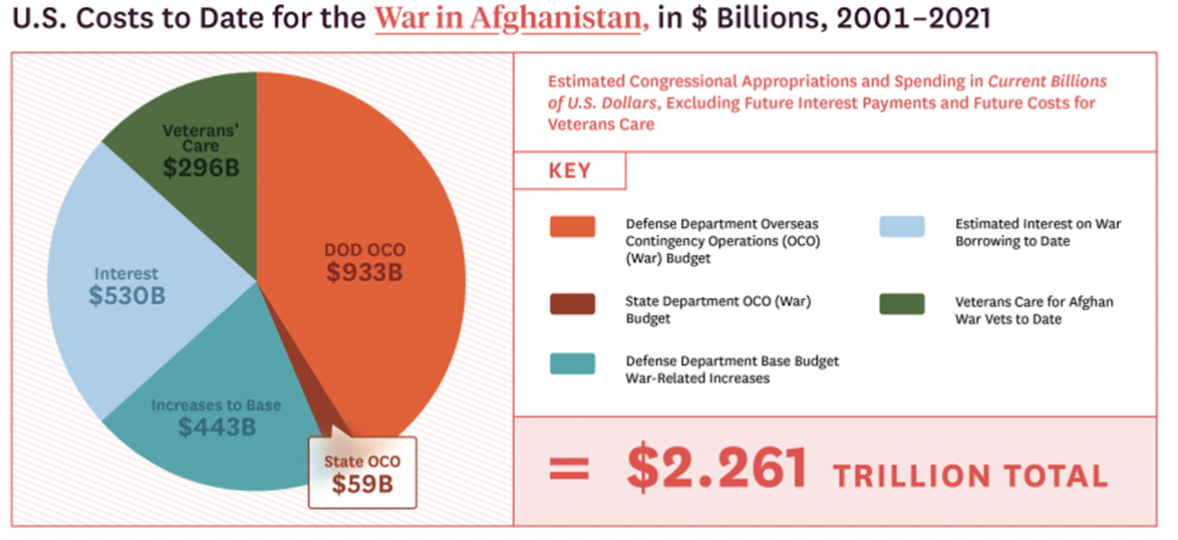

If you look at this breakdown, you see how little of it has anything to do, even in theory, with helping Afghans. Most of it is money for keeping untenable bases in Afghanistan and the rest is cost-of-doing-business, including a giant chunk for veterans’ benefits.

Here’s another breakdown showing the same massive tilt toward the Blob and its shareholders.

You can’t miss the tilt, with almost the whole 2.1 trillion dollars going to DoD contractors and a miserable $24 billion spent on economic development. That means that over two trillion went to dividend holders, private contractors, spies, and moonlighting cops.

The wonderful thing about this kind of spending, in the deeply corrupt lobbyist world of DC, is that it shunts tax dollars directly to the stockholders, connected military firms like Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, et al., legislators, military brass milking the DoD/corporate link, and even lowly CIA contractors like Johnny Spann —without angering a single taxpayer or benefitting them in any way.

When I say that this sort of obscene spending does not upset taxpayers, I’m speaking from bitter experience. You cannot get normal Americans to be upset about the price of junk like the F-35. I’ve tried. You can’t do it.

The only item in this breakdown which would upset most people is the $24 billion that might have made its way to Afghans. If you mention any of those other expenses, you’ll get “Freedom isn’t free” in one of its many variations, which vary only in diction. Try it! Hours of non-fun!

Who wouldn’t feel the temptation to prolong a money-spinning machine like this? So why wouldn’t the occupation become its own justification, the company business of DC, always a company town?

And so, rather than upset their fellow shareholders, GWB, then Obama and Trump, just nodded and smiled at the conveyor-belt of $100 bills.

Once you consider this theory, some strange trends make sense.

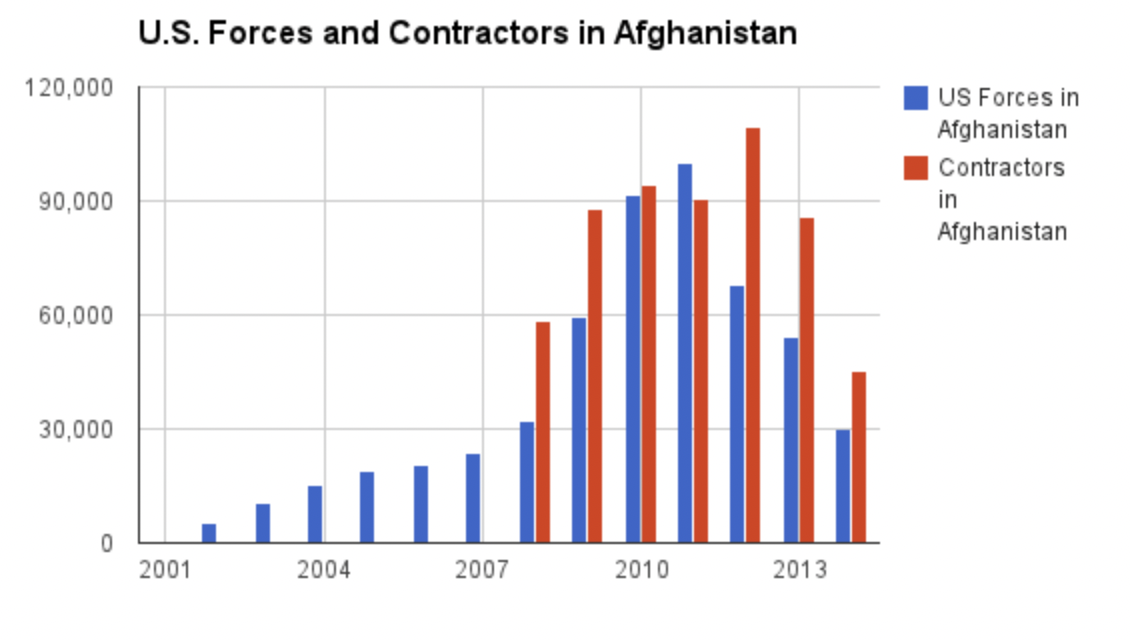

The one that struck me is that in 2007, when Iraq was in crisis and Afghanistan was clearly lost, Cheney’s people made a big, expensive switch in the Personnel Department, drawing down the much cheaper and more effective US Army troops and flooding Afghanistan with much more expensive, less effective private contractors. You wouldn’t do that if you wanted to win in Afghanistan, but you would if you wanted to spend money within the Blob (specifically the Erik Prince wing) and insulate a doomed Afghan war from public criticism by keeping official US Armed Forces casualties low.

It’s an appalling vista, as Lord Denning might say. But it’s the only way to make any sense of this story.

8. “Yeah We Messed It Up But It’ll Get Worse When You Make Us Leave”

And so we come to the final stage, which in this case is not “Acceptance” but muttered sulking. It’s been a while since anyone claimed “we” could “win” in Afghanistan. The only argument for staying is that “things will get worse if we leave.”

“…If the US left, that war would be much worse, and you’d probably see the Afghan government collapse pretty quickly. Even though we do have war now, it’s not an all-out civil war with no state: We have a state, we have an Afghan security force.”

You can probably guess the most famous voice in this chorus — Hillary herself:

“Asked about the president’s decision by CNN’s Fareed Zakaria on Sunday, Mrs Clinton said, ‘Our government has to focus on two huge consequences,’ notably the resumption of activities by extremist groups and a subsequent outpouring of refugees from Afghanistan.”

That’s Fareed Zakaria interviewing Hillary Clinton…in 2021. It seems impossible, unreal, that these zombies are still walking around — and not just walking but talking. That’s the unreality of the US- Afghan War, 20 years of sinking slowly into the dirt like that Beckett play, while keeping up a constant, insanely sanguine and sanguinary chatter.

The two US invasions will be covered thoroughly in future histories of American decline, but Afghanistan will be remembered very differently from Iraq. Iraq was the great, shining disaster, the full-speed collision of world-building fantasy with actual world. Afghanistan was something else, smaller yet even darker.

It may well be that those who mattered in the US elite never even thought that the Afghan part of the grand plan would work. It was doomed many times over: by the well-known collusion of the (Afghan) Taliban and the Pakistani state; by the caricature of Afghans as noble savages, brave but hopelessly primitive; by the warped free-market doctrine that sidelined Afghanistan’s leftist elite; by competition from the preferred Iraq project; by the massive profits to be made stateside, no matter how badly things went on the ground.

Those profits are still available, which means this withdrawal won’t really happen, or will be yet another bit of show biz, with private contractors (who can be paid via unspecified agency money) staying on, doing various kinds of work, both wet and tech. Afghanistan may still be good for another trillion or so — off the books, of course.

Gary Brecher is the nom de guerre-nerd of John Dolan. Buy his book The War Nerd Iliad. Hear him read his comic memoir Pleasant Hell in audiobook format.

Subscribe to the Radio War Nerd podcast & newsletter!

August 16th, 2021 | Leave Comment