Actually their aversion to fighting the Red Army was a lot more reasonable than most of their other zany ideas. They got it the hard way, by getting crushed in battle against the Red Army in Mongolia back in the late 1930s. Back then there were two factions in the Imperial Japanese forces, the “Northerners” and the “Southerners.” Both sides wanted Japan to go forth and conquer; it was just a question of where. The Northerners shrieked that it was Japan’s destiny to seize Eastern Siberia from the Russians, whereas the “Southerners” wanted to grab SE Asia and the Pacific Islands from the US. Roughly speaking, the Imperial Navy favored the Southern strategy, and the Army favored the Siberian option, for the same reason Bush Sr. used to give for the first Gulf War: jobs, jobs, jobs. The Siberian strategy meant the Army would have the leading role; the Pacific plan would put the Imperial Navy in the driver’s seat.

The Army got its chance to show what it could do in a mainland-Asian war against the Soviets in 1938, with an indecisive bloodbath between Japanese and Russian troops at Khasan Lake. The Imperial Army didn’t take the Russians seriously enough, and they figured that bloody draw was a fluke. One more chance and they’d stomp the Russians like they had in Port Arthur and the Tsushima Straits a generation back. You can’t blame them too much; a couple years later, a guy called Hitler had the same idea about how easy it was going to be to stomp the Russians.

Not these post-Revolution Russians, baby. This wasn’t the Tsars’ clanky old family-mismanaged business, but the Red Army (didn’t switch to “Soviet Army” till 1946). Sure, Stalin had purged the officer corps in the Terror of ‘37, but he was smart enough to keep one very important man alive, even though this guy had once been a Tsarist officer: Georgi Zhukov. I understand there’s a statue of him on horseback in Moscow, and I’d appreciate it if some of you Russian readers would lay a wreath or something by it this weekend on my behalf. I’ll pay you the next time I’m in Moscow, promise. Spa-see-bo, if that’s how you say it.

Zhukov is one of the 20th century’s great commanders. The Russians gave him the same title the Mongols gave Subotai and the Greeks gave Alexander: “the one who never lost a battle.” Weird, but I never heard much about him growing up. I knew who he was, of course, but those Cold-War books were a little stingy handing out praise to Soviet generals. Me, I’m not political. I celebrate Zhukov for what he was, a genius at combined-arms attacks. He reminds me of Alexander more than anybody else, and you can’t get higher praise than that. Too bad he was serving Stalin, sure, just like it’s too bad that magnificent Wehrmacht was serving Hitler. But I still salute the Wehrmacht and I still salute Zhukov. Hey, getting yourself a war to command is even tougher than getting a movie to direct, takes even more capital and cooperation from all kinds of prima donnas. A general’s got to go where the work is, and one thing you can say for those 1930s wacko dictators, they gave the generals plenty of chances to showcase their skill sets.

Zhukov is one of the 20th century’s great commanders. The Russians gave him the same title the Mongols gave Subotai and the Greeks gave Alexander: “the one who never lost a battle.” Weird, but I never heard much about him growing up. I knew who he was, of course, but those Cold-War books were a little stingy handing out praise to Soviet generals. Me, I’m not political. I celebrate Zhukov for what he was, a genius at combined-arms attacks. He reminds me of Alexander more than anybody else, and you can’t get higher praise than that. Too bad he was serving Stalin, sure, just like it’s too bad that magnificent Wehrmacht was serving Hitler. But I still salute the Wehrmacht and I still salute Zhukov. Hey, getting yourself a war to command is even tougher than getting a movie to direct, takes even more capital and cooperation from all kinds of prima donnas. A general’s got to go where the work is, and one thing you can say for those 1930s wacko dictators, they gave the generals plenty of chances to showcase their skill sets.

Zhukov, like a lot of the great 20th century commanders, started out as a cavalry officer. Not a great career choice in most parts of the world in the early 20th-century, but in the Russian Civil War, where Zhukov played his rookie season, cavalry was still important—lot of ground to cover, mostly flatland, no roads worth mentioning. The machine gun and barbed wire looked like they were finishing off cavalry forever on the Western Front during WWI, but a few smart horse officers realized that you could use these tank thingies not just as screens for infantry advance but as bulletproof cavalry, doing the same old dashing advances J.E.B. Stuart would have recommended. The only difference was in logistics: the new cavalry advance had to be a way more carefully prepared business than the old saber charge, with logistics assuming a huge role.

When Zhukov assumed command of the Soviet forces in Mongolia (June 1939), there’d already been two months of straggling border skirmishing, escalating from a proxy fight between the Russians’ Mongolian allies and the Japanese’s Manchurians, to full-scale armored engagements between the Japanese and the Red Army.

What Zhukov did way back in 1939 set the pattern not just for the Red Army’s successes against the Germans but for that final, perfect campaign against Japan in Manchuria in 1945. First, Zhukov dealt with his logistical problems, something the Japanese were too mystical and transcendental to take seriously. Next, he made sure all arms were in total coordination: air force, armor, infantry, artillery. That was another thing the Imperial Japanese were too snotty and quarrelsome to do: from 1919 to 1945, one of the constants in Japanese conduct in Manchuria is that the services hated each other, fought among each other all the time. In 1945 that meant that the Navy refused to lift a hand to help stranded Japanese troops evacuate the Asian mainland; back in 1939, it meant that when the Japanese air force launched a successful attack on Soviet airfields in Mongolia, jealous local commanders ordered their pilots to halt all attacks.

In August 1939—you Russians must like hot weather, you seem to do a lot of your big attacks in August—Zhukov had all his ducks in a row, and gave the word to attack. Remember, attacking wasn’t something most commanders in 1939 did easily. They’d learned in 1914-1918 that the advantage was with the defenders. Only a few guys like Patton, Rommel, de Gaulle and Zhukov realized that that wasn’t necessarily so any more. Zhukov showed how it was done by encircling and annihilating the Imperial Japanese forces in Eastern Mongolia. And I do mean annihilating, because as usual, Japanese troops just didn’t surrender, so after Zhukov’s pincer attack surrounded them and they’d turned down a trip to the GULAG, Soviet artillery wiped them out.

|

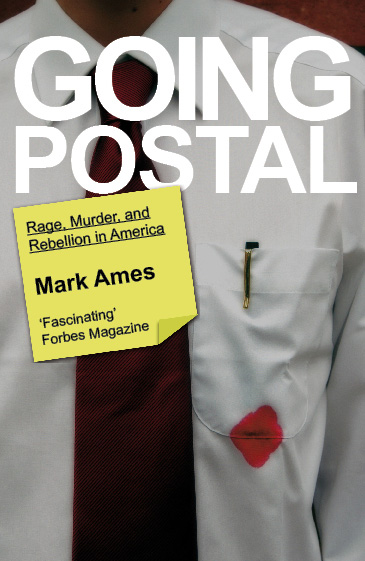

| Zhukov crippled Japan’s Imperial Army, much as this photo-caption is crippled with tasteless irony. |

Another little preview of 1945 during this battle was the way Japanese troops dealt with the inevitable, as in “total denial,” aka: “brave but stupid.” One Japanese officer supposedly led his men on foot in an attack against Soviet tanks, with his Samurai sword on high. That was a pattern you were going to see again and again, in Saipan, Okinawa, the Philippines, everywhere Japanese troops were defeated: they thought way too much of arranging glorious deaths for themselves, and not nearly enough about arranging the same thing for the enemy.

But this time, in a rare moment of reason, the Imperial Armed Forces learned their lesson: after meeting Zhukov and getting slaughtered next to that frozen Mongolian river, they lost all appetite for a land war against the Soviets. Now, the Japanese were all for headin’ south, to the sea and sun, to those balmy Pacific beaches, starting with Pearl Harbor.

That little shift in Japan’s business expansion plan kept them pretty busy. So now we can fast-forward all the way to 1945 without losing much, because while the whole rest of the world was exploding, in the meantime, the USSR-Japanese borders in Manchuria/Siberia didn’t so much as flicker from 1939 to 1945. Nothing, zip, nada going on for all that time. Stalin kept 40 divisions there (remember, a Soviet division was only 11,000 troops), but thanks to Richard Sorge’s Tokyo spy ring, he knew the Japanese weren’t interested in another big fight in Manchuria, which made planning for the German front a lot easier.

So now it’s May 1945: “Hey Comrade Stalin, you’ve just won the Super Bowl! Where are you going?” Well, it wasn’t Disneyland; “I’m goin’ to Manchuria!”

And like I said earlier, he was in no hurry to get there, because every day the Japanese were weaker. The B-29s ran the Tokyo route more often than commuter flights from SFO to LAX. The last of the island fortresses were falling—and instead of reinforcing the Manchurian Front, the Japanese Imperial Command, in its usual psychotic state of total denial about the Soviet threat, was actually sucking every decent infantry and armor unit away from the Kwantung Army in Manchuria and feeding them into the hopeless war against the US advance toward the Home Islands.

I came across an amazing story of this one cool Japanese officer who was caught in that transfer. Actually, there are a lot of amazing stories in this Manchurian campaign, but this guy is a classic: Takeichi Nishi, also known as “Baron Nishi” when he used to hang out with the stars in Beverly Hills. Nishi was a child of the Japanese elite, a nobleman and a famous Olympic horse-riding star, and he spent a lot of pre-war time going to snooty horse-riding tournaments in Hollywood, driving his convertible around waving to all those silent-movie stars.

Read more: eXile Classic, exile issue 288, stalin, the war nerd, Gary Brecher, eXile Classic

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed