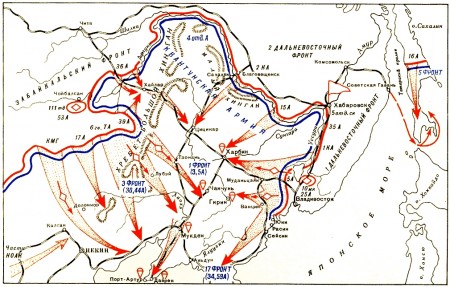

A map of Zhukov’s attack on Japan’s Imperial Army bears a strange resemblance to the inner jaws of those giant sandworms in Dune

Everybody knows about the Fall of Berlin. You Russians will be out in the streets next week doing your Victory Day thing commemorating the capture of the Reichstag, Hitler eating Luger lead, and—on a sadder note—the end of the long, sweet rape-fest Russian soldiers enjoyed on their triumphant march through Prussia.

| Browse Column |

Yes, their happy thoughts of home and hearth were tempered, as the preachers say, by the realization that their big Woodstock of free, forced love was about to come to an end.

What most people don’t know is that the Red Army had another huge triumph still to come: a crushing strategic victory on a front 3000 miles long, with 1.6 million Soviets annihilating a force that, on paper at least, totaled more than a million battle-hardened Axis troops. I’m talking about Operation August Storm, the Soviet invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria on August 9, 1945—exactly three months after the surrender of the Nazis.

That date is no coincidence. Stalin was a smart shopper, with the gift of timing—if he’d been born a little later and Wester, he would’ve got rich on eBay, gotten into breeding Shih Tsu or something, and all those people wouldn’t have had to die. Anyway, Stalin made a deal with FDR and Churchill at Yalta (Feb. 1945). It was clear by that time that the Germans were finished, and now it was the Americans’ turn to demand a second front to ease their war burden, this one against Japan.

So Stalin signed on the dotted line: he’d invade Japan’s Manchurian colony within three months of the defeat of the Nazis. The deal was, he had to meet that yardstick—it was like one of these NFL contracts with incentive clauses, the ones they do when the draft choice has loads of talent and a massive coke habit. The Big Three, Stalin, FDR and Churchill, were all smiles at the photo ops, but not stupid enough to trust each other. So Churchill and FDR put in a sweetener for their Soviet pals: if the Red Army attacked Japan’s Manchurian colony within three months of the Nazis’ final defeat, the USSR would get permanent occupation of Sakhalin Island, a big long streak of icy forest north of Hokkaido, and the Kuril Islands, a string of fog-bound rocks looping from the North end of Hokkaido to the Southern tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Not exactly Rodeo Drive in terms of valuable real estate, but those places meant a lot to Stalin: they’d been grabbed from the Russians by the Japanese in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05. It was one of those old disgraces that world powers tend to get all obsessive and unhealthy about, like Hitler forcing the French to surrender in the same lousy railroad car where they’d made Germany surrender in 1918. That was what pre-Abba Europe used to be like: never learned anything new, and never, ever forgot a grudge.

There was something kind of poetic-justice about the way the Americans were begging the Soviets to open up a second front against the Japanese, because the Russians had been begging the Anglos to open a second front against the Germans for years—two-and-a-half years, actually, counting from Pearl Harbor (Dec. 7, 1941) to D-Day (June 6, 1944).For all that time, the Soviet armies had fought alone against the Wehrmacht, the finest land army since the Mongols. And all that time they were screeching, “Hey Allies, buddies, ol’ pals, how about a LITTLE HELP HERE!”

The Anglos had some pretty good excuses, like the fact that the US was gearing up as fast as it could, passing most of its industrial production directly to its allies while dealing with the Japanese in the Pacific—but to the Soviets, who lost at least 20 million people to the Germans, those years of waiting for the Normandy front to debut seemed like a real long time. I read somewhere that there was a joke making the rounds in wartime Moscow:

Q: What is the definition of an optimist?

A: Someone who believes in a second front.

Pretty lame, joke-wise, but I guess it wasn’t adaptive for Russians to make any really smart jokes while the NKVD was listening. Anybody who got any wittier than Yakov Smirnov was likely to win a free GULAG tour package. And at least the joke makes my point: for Russia, those three years were like trying to hold off a rabid grizzly while your allies kept saying in a cheerful-asshole voice: “Be there in a sec! Just hang in there, think positive!”

So Stalin had every reason to turn the tables now, let the Americans bleed the Japanese in the Pacific up till the last moment possible, wait until the Imperial forces were a shell, then send in the T-34s. The fact that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria came exactly three months after the fall of Berlin, the maximum time allowed under the Yalta Agreement, might suggest to some of you cynical folks that the generalissimo was biding his time.

But you have to remember, Spring and Summer 1945 was a busy time for all concerned. The Russians were busy rounding up all the surviving Wehrmacht troops and allies (and the Wehrmacht had a lot more allies than anybody wants to talk about these days), maneuvering for position in postwar European power politics, and trying to deal with all the sheer destruction the Germans had visited on Western Russia. The Japanese had to watch their Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere wiped off the map, island chain by island chain. Even on the Home Islands there was a lot more than cherry blossoms falling that Spring. On March 9, the new B-29 Superfortresses dropped incendiary bombs that gutted Tokyo and killed more people, maybe—they’re still not sure but the estimates go up to 200,000—than the A-bombs that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, just before the Soviets struck Manchuria.

The Japanese had a weirdly passive, almost hopeful attitude toward Stalin anyway, going way back to the early 1930s. Right up to the end, they kept hoping he’d let them alone, or even broker a peace deal that would keep the Americans out of Japan. They were all for fighting to the death against the Yankees, but they kept dreaming that Uncle Joe had a soft spot for them.

Bizarre, but then one thing you notice when you study Imperial Japanese “thought,” if you can even call it that, is that they weren’t much on cold-blooded analysis.

Read more: eXile Classic, exile issue 288, stalin, the war nerd, Gary Brecher, eXile Classic

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed