He was also a cavalry officer in the Imperial forces, which wasn’t so much fun, especially when his unit was transferred from Manchuria to Iwo Jima in 1944. His unit didn’t even make it to Iwo: they were torpedoed en route and all their tanks are still rusting somewhere on the Pacific sea floor, condos for the hagfish. Nishi and his men survived the sinking, all but two of them, and made it to Iwo Jima, even got new tanks. But they were ordered to bury them up to the turrets. Not much chance for maneuver warfare; this was going to be one of those suicide stands Showa-era Japan loved so much.

The Americans were all for that, usually: “Here, we’ll hold the bayonet and you run onto it!” but—and I have to admit, this is kind of touching even for me—they knew that their old Hollywood buddy “Baron Nishi” was on the island and they didn’t want to hurt him. So they actually sent guys with bullhorns around the island saying, “Paging Baron Nishi, paging Baron Nishi! Please surrender at the front desk, you can have your horse back and everything! Free tickets to the new Clark Gable flick! C’mon, don’t be a sore loser!” But the dude was an Imperial Japanese officer; they weren’t always smart but they were hardly ever chickenshit. Eventually they found him: crisped by a flamethrower, still wearing his riding boots.

So that, in a crispy-fried nutshell, is what happened to the best units of the Kwantung Army while it waited with its head down in bunkers all along the 2000-mile front facing the Red Army: all its best troops were gone, dead in pointless outpost defenses, and all its armor was gone. The Soviets were going to have a wonderful time of it. They were going to do this like a victory lap, a tour de force, a training video.

This was a campaign between two great empires—both gone now, it occurs to me—but one, the Soviet, was at the absolute top of its game, and the other, Imperial Japan, was dying and insane. There were still about 700,000 Japanese and Korean troops holding the line in Manchuria, but they weren’t exactly Samurai-quality. A full 25% of the Kwantung Army’s strength was guys who’d been drafted in the two weeks preceding the Soviet attack. We’re talking about an army that looked like John Bell Hood at Atlanta, missing an arm and a leg and not top-drawer material to start with. The amazing thing is that the Japanese troops knew it themselves. They were the dregs, dragged out of junior-high classrooms and old-age homes and shelters for the hopelessly useless, and they called themselves names that sound like a Heavy Metal amateur night at your local bar: “human bullets,” “Manchurian orphans,” “Victim Units” and “The Pulverized.” (If you don’t believe me, check out Philip Jowett’s book, The Japanese Army 1931-1945, page 22.) Their official strength was 24 divisions, but that translated to about eight divisions of effectives, with only about 1200 light armored vehicles.

Against that was a force that God would have made excuses to avoid facing in the Octagon: 1,600,000 battle-hardened Soviet troops with 28,000 artillery tubes and 5000 tanks—and more than 3000 of those were T-34s, the best tank in the world at that time. (You tank nuts who disagree with that assessment can send me all the King Tiger sites you want; it was a nice blueprint but they tried it against the T-34s and it LOST, and I kinda go by success in battle, not bluebook-style stats.)

The Red Army had learned a lot about logistics since 1941, and some of the moves they made to prepare for the assault on Manchuria were pretty amazing. Instead of trying to transfer thousands of tanks across the whole Eurasian landmass from Eastern Europe to Manchuria, the Russian armored units like the 6th Guards Army, one of Zhukov’s best, left their tanks in Czechoslovakia before the engines even had time to cool down, hopped into troop trains and crossed the continent to meet up with fresh new tanks, shipped from factories east of the Urals, when they arrived on the Manchurian front. By August 1945, the Russian supply lines were running so smoothly that they could ship pretty much anything anywhere it was needed. Like Soviet armies always did, they took logistics and surprise both dead seriously, so they ran up to 30 trains a day across Asia, but I should say “a night,” because to keep tactical surprise they ran all those trains at night. (If you want a great detailed account of the prep the Soviets took, read Col. David Glantz’s book The Soviet Strategic Offensive in Manchuria, 1945.)

The combination of logistical superiority and tactical surprise gave the Red Army commanders a lot of flexibility when they looked at the maps of Japanese-held Manchuria. First, a little geography: Manchuria is sort of like a box, with high mountains and big rivers along the borders, sloping down to flatland in the middle. The middle part of the province was the prize; that’s where the fertile land, the population and the industry was concentrated. Most of the Japanese defensive forces were concentrated on the east side of the box, where they faced off against the Soviets along a north-south line following the Ussuri River from Khabarovsk down to Vladivostok.

The Kwantung Army commanders expected the Russian push to come from the east, and what defenses they had were concentrated there, especially around a town called Mudanjiang—tiny place by Chinese standards, only three million people in it even today.

The whole western border, butting up against Mongolia, was left all but undefended. To attack from that direction you’d have to cross the Gobi Desert, which the Japanese considered impossible, then go over the Khingan Mountains, which hit about 5500 feet and are what BLM would proudly call a “roadless area.”

The whole western border, butting up against Mongolia, was left all but undefended. To attack from that direction you’d have to cross the Gobi Desert, which the Japanese considered impossible, then go over the Khingan Mountains, which hit about 5500 feet and are what BLM would proudly call a “roadless area.”

So if you’ve read any military history you can guess where the Soviets put their biggest forces: yup, due west, ready to storm across the Khingan Mountains. Of course this put a huge strain on their supply lines, but that was nothing for a force as tough and experienced as these dudes.

Oh, that wasn’t their only attack front. In fact, they attacked everywhere. Like I said, when you study this campaign you get the sense that the Red Army was putting on a show, doing a demonstration of Suvorov’s old line, “Train hard, fight easy.” They’d sure trained hard, and lost a whole generation doing it; but the survivors seemed like they were almost having fun with it, running a clinic.

On August 9, just in time to claim Comrade Stalin’s prizes (Sakhalin Island, the Kurils, Korea), the conductor waved his baton and the whole magnificent slaughter ballet started up. They attacked EVERYWHERE. They attacked from the southwest, right across the Gobi, and one column even came up through Kalgan, in rock-throwing distance of Peking (hey, it was still Peking back then). They rushed south from Khabarovsk, and west from Vladivostok. That was the one place they ran into trouble, at that little town of Mudanjiang, where the Japanese had dug in like gophers expecting the Rapture. The Red Army had 11,000 casualties, one third of its total for the whole campaign, in the attack on Mudanjiang.

I mean, it was like they were showing off. They dropped paratroopers on Harbin, the big prize, in the dead center of the Manchurian plain, and other parachute units on Mukden. Best of all, they dropped in on Port Arthur and Darien, site of Russia’s big humiliation in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5.

Everything went right. It’s too bad we’re too stubborn to give a little appreciation to ex-enemies, because if people knew more about this campaign they’d enjoy the Hell out of it, just for the sheer beauty of the plan and execution.

Like all advances that work better than they’re supposed to, this one stalled because it literally ran out of fuel. Those T-34s got so far inside Kwantung Army lines in the first few days that the Soviet Air Force had to use DC-3s to bring in gas. By that time, it was pretty clear that the cannon fodder the Japanese had left to man the trenches had had enough, so the problem wasn’t so much defeating the Axis forces as beating the American naval task forces down to the Korean Peninsula, the one big strategic objective the Red Army hadn’t yet overrun. They made it about halfway down the Peninsula, and then had to stop because a US force had made a landing at Inchon—yup, the same Inchon that MacArthur was going to make famous a few years later. That’s how the Korean Peninsula came to be divvied up halfway down, like an Xtreme circumcision: because that’s as far as the Red Army’s tanks got before the US Navy’s landing crafts started unloading the USMC. We were still “allies,” of course, but we were already the kind of allies who playfully go for the carving knives when there’s a piece of chicken still on the table, chuckling all the way. Or as Pol Pot said of the Vietnamese in the early 70s, “Friends, but friends with a conflict.”

The Red Army still had jobs to do, because Stalin’s armies were always about more than just conquest. For one thing, they had to dismantle the whole industrial infrastructure of Manchuria—pretty considerable, too—and ship it back to the USSR “for safekeeping.” Then they had to corral the 600,000 surviving soldiers of the Kwantung Army. Most resistance was over by August 14, 1945, but a few units held out longer, until the Emperor’s surrender broadcast—which most of the Japanese alive in 1945 still remember as the most crushing event in their lives—filtered down to the bunkers and foxholes all along that 3000-mile front. When they were all rounded up—well, this IS Stalin we’re talking about, so you can’t get too sentimental; what do you think he did with them? Nah, didn’t kill ’em—too wasteful. Instead all 600,000 Japanese POWs were herded into cattle cars, the cars were boarded up, and the whole of what used to be Imperial Japan’s proudest army ended up in freezing prison camps.

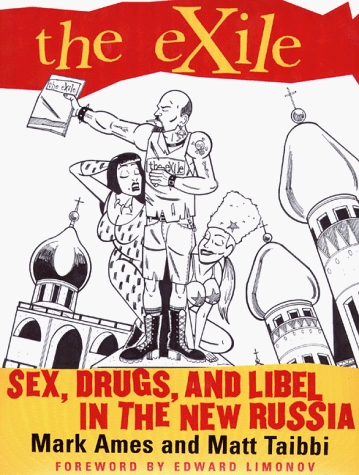

Read more: eXile Classic, exile issue 288, stalin, the war nerd, Gary Brecher, eXile Classic

Got something to say to us? Then send us a letter.

Want us to stick around? Donate to The eXiled.

Twitter twerps can follow us at twitter.com/exiledonline

Leave a Comment

(Open to all. Comments can and will be censored at whim and without warning.)

Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed