Republished from the Radio War Nerd subscriber newsletter. Subscribe to the Radio War Nerd podcast hosted by Gary Brecher & Mark Ames for podcasts, newsletters and more!

Belarus is headlining war news again — Russia is preparing a fresh offensive against Ukraine from Belarus, the main staging point for its original offensive last year to take Kyiv. Or at least that’s what they’re saying.

What’s lost in these stories is how strange and impossible it would’ve been just a couple years ago to imagine Russia being able to use Belarus as a staging ground for its military offensives. We’ve already forgotten that as recently as 2020, Lukashenko was flirting with NATO partnership, hosting anti-Russia hawks Mike Pompeo and John Bolton, and denying Russia the right to set up an airbase in Belarus (let alone hosting an entire invasion force).

Then came the big western-backed regime-change movement to overthrow Lukashenko and replace him with the West’s favorite, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya — and the next thing you know, Belarus is the Russian military’s doormat, to do with as it pleased.

Russia-Belarus relations pre-autumn 2020 regime-change movement

Russia-Belarus relations pre-autumn 2020 regime-change movement

In our end-of-2022 RWN episode, we discussed one of the biggest overlooked factors that would’ve influenced Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine the way he did, when he did: Belarus. The story is a bit complicated and can get a bit tricky to follow in a podcast, and some subscribers either had followup questions or requests for some clarification. So we figured the easiest thing to do would be to write out the scenario we discussed. Makes it easier to remember some of the names and events this way.

To recap: in December 2022, the New York Times published a massive graphics-heavy, multi-bylined investigation, “Putin’s War”, into the origins and conduct of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, using allegedly leaked classified battle plans, intercepts, and good ol’ NYT hackery. The article has everything you’d expect from the Times: it’s a slippery cocktail of lies, propaganda, and occasional revelations, and it’s up to you the reader to sort it all out, if you have the time & energy.

The stated purpose of the graphics-heavy investigation, according to one of the authors, Anton Troianovski, was to answer “one of the central questions of the war in Ukraine: Why has Russia bungled its invasion so badly?” Leave it to the Times to use that word “bungled” — you won’t ever hear it in the natural world, but by gum they love their “bungled” in establishment medialand.

Anyway, ever since the second week or so into the war, westerners have enjoyed nothing more than ruminating over Russia’s military failures. Russia’s crimes, of course, are also a hot topic; but for sheer joy and self-esteem boosting, nothing beats obsessing over Russia’s failures. Because to ask “Gosh, why does Russia’s military suck so badly?” is to gloat, O sweet gloat, and that is its own reward, more soothing now to the Acela Corridor than in living memory, after a string of 21st-c. US military defeats (or “bungles,” in the parlance of The Times.)

The problem is that while focusing on Russia’s litany of screwups reminds us how totally awesome we are (and helps us forget our egg-shaped GWOT-era war record), it distracts from one of the great mysteries of the war: Why did Putin decide to wage the war the way he did — a large-scale invasion centered on overpowering Kyiv and decapitating Ukraine’s government — when he did, in February 2022?

There’s an unspoken assumption today that could not have been simply assumed 18 months before Putin’s invasion — the idea that Belarus was always Putin’s doormat to use as he pleased. That’s an entirely new input, Belarus’s total submission to Moscow, and it can’t be relied on to last much longer if recent Belarus-Russia history is any guide.

Instead of investigating the Belarus assumption in Putin’s war plan, the NYT dabbled in weird body language quackery to try to answer why: “Some reported with concern that ‘he’s got this warlike twinkle in his eyes,’ a person close to the Kremlin said.” Serious people have put forward other theories to explain Putin’s war plan and timing: that he suffered from some kind of covid isolation psychosis, ‘roid rage, cancer, parkinson’s, a strange smell, and so on. Naturally, the Times goes there too: “A former Putin confidant compared the dynamic to the radicalization spiral of a social media algorithm, feeding users content that provokes an emotional reaction.”

But all this mushy pop psychologizing leaves a lot to be desired. For a lot of us who’ve been writing about Putin over the years, the war didn’t fit the Putin pattern — a sort of highly pragmatic, low-key malevolence – we’d grown used to. Psychologizing about the warlike twinkle in his eye may be titillating to the Times readers, but meaty explanation it ain’t.

One thing the big NYT opus reminded us of was how taking Kyiv was the centerpiece of Putin’s initial February 2022 Russian invasion plan. He calculated, wrongly, and far as I can tell very stupidly, that Ukraine would be too factionalized, corrupt and dysfunctional (ie, too Ukrainian) to put up any serious resistance — that they would be overwhelmed by the shocking scale of the invasion, and that by taking Kyiv, Russia would either capture or chase out the western-backed regime, and replace it with…with what?

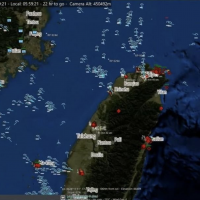

So, the plan was to take Kyiv. And the way Russia planned to take Kyiv was by invading from the closest point to Kyiv — Belarus, whose border with Ukraine is a direct line north of Kyiv, rather than from Russia proper, which is much further away, or via the heavily-fortified Donbas.

Putin’s entire invasion plan in February 2022 hinged on using Belarus

This is the part of the story that’s been lost: Belarus as the lynchpin to Putin’s initial war strategy of taking Kyiv. The initial thrusts against Kyiv all came from Russian forces massed in Belarus, whose southern border is far closer to Kyiv than anywhere in Russia or the Russian-backed Donbas. Put simply, it’s much easier to plan an armored assault on Kyiv from Belarus than from Russia proper.

Since the war started, we’ve forgotten about all the problems Russia had in its relationship with Belarus and just assumed that it’s somehow natural and obvious that Putin could use Belarus to stage his invasion. Because after all Belarus is led by another authoritarian baddie, Alexander Lukashenko. And as we’re told over and over these days, authoritarians are genetically prone to liking each other, and they do baddie solids for each other. Because that’s what bad guys do in DC or Marvel comics: they baddie up together, and laugh evilly when they’re together doing their baddie thing.

But before August 2020, there was no way Russia could have used Belarus to invade Ukraine. A year earlier, in 2019, Belarus wouldn’t even allow Russia to set up a new airbase in Belarus to station Russian Sukhoi-27s, let alone host a massive Russian invasion force.

In fact, right up to August 2020, the United States and the EU were making a huge play to peel Belarus away from Russia’s orbit, while at the same time, Belarus’s dictator Lukashenko was publicly attacking the Kremlin for “meddling” and “puppeteering” the anti-Lukashenko opposition. He was jailing Kremlin-backed Belarussian politicians, and mass-arresting and torturing Russian military contractors on charges of attempting to stage a pro-Kremlin coup. Relations were nearly at the breaking point…

And yet, 18 months later, Russia was able to use Belarus as it pleased.

What changed in August 2020 was a massive protest movement in Belarus, backed by the West, to overthrow Lukashenko and replace him with the western-backed opposition candidate, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya. It was this failed western-backed regime-change movement against Lukashenko — and the sanctions imposed by the EU and Washington to isolate and collapse Lukashenko’s regime — that once and for all forced Lukashenko to stop playing both sides off each other, and instead throw himself at Putin’s mercy to save his regime. For a couple of months in early autumn 2020, the smart money was on Lukashenko going the way of Yanukovych, Ceacescu and other color revolution losers — but Putin, after waiting for Lukashenko to get so desperate for help he’d agree to any of Putin’s demands, came in and saved Lukashenko’s regime. And in return, for the first time in their 20-year frenemy relationship, Putin got whatever he wanted from Lukashenko.

To understand how this happened, we have to go back and recover the recent history of Russia-Belarus relations, which was often thorny, as they say, sometimes outright hostile, but never as master-servant as it is today ever since the failed western-backed protest movement a couple of years ago.

Some history: Lukashenko was first elected president of Belarus in 1994 running against the catastrophic neoliberal politics — privatization and westernization and hyperinflation — that destroyed Belarus’s economy and left most people in wretched poverty, much like in neighboring Ukraine and Russia. That 1994 election is generally considered post-Soviet Belarus’s only “free and fair” election, and Lukashenko won it with 80% of the vote, promising to end shock therapy hyperinflation by freezing prices and bringing back something like a Soviet-style semi-command economy; crushing capitalist mafiosi and corruption; and moving Belarus closer to Russia rather than to the West.

Russia at that time was the poster child of Washington-backed neoliberalism, and the Yeltsin regime’s leading figures were fanatical anti-communists, so they were wary of Lukashenko’s revanchist politics catching on in Russia, where Yeltsin was deeply unpopular. But Yeltsin’s security structures were all in favor of deepening ties with Belarus — and anyone else who wanted closer security ties with Russia, a tiny club in 1994 that was shrinking by the day. And politically, just having a neighbor like Lukashenko saying he wants to deepen ties with Russia was good populist politics, even if Lukashenko rejected Yeltsin’s neoliberal program.

While Russian state television savaged Lukashenko as a throwback hick and dangerous buffoon, in 1997, Yeltsin and Lukashenko signed a union agreement that started the process of integrating the two countries — or at least, pretending to integrate them. In December 1999, just before Yeltsin resigned and handed power to Putin, he and Lukashenko created a more formal Russia-Belarus superstate with a High Council and plans to unify their currencies and other structures. For Lukashenko, a fully integrated union could have been a way for him to take control over the superstate itself — ie, Russia — given how unpopular Yeltsin was. At the very least, it meant cheap, subsidized Russian products, particularly fossil fuels, that helped Lukashenko stabilize Belarus’ economy and inflation, and allowed him to create a weird sort of semi-Soviet, semi-socialist state that actually managed to work, contra all orthodox free-market theory of the time.

And Lukashenko’s semi-soviet economic model did work. In 2018,Belarus’s GDP per capita was more than twice as high as neighboring Ukraine’s, and higher than all the FSU countries except for Russia and the Baltics. As Bloomberg noted in late 2019:

“[Belarus’s] transition from command to semi-market economy, delivered at the speed of a mud-bound tractor, has by some economic measures made this a better place to live than any other former Soviet republic, barring the three Baltic States that joined the European Union. Belarus scores better on inequality than any EU nation (including the likes of Denmark), and has a smaller percentage of people living [in] poverty than any other part of what was once the Soviet Union, half of the EU’s 28 member states, or the U.S.”

But when Yeltsin handed power to Putin in 2000, he pretty much ruined any big plans Lukashenko might’ve had of George Jefferson-ing his way on up from ruling little Belarus, to taking over a giant Russia-Belarus superstate. Unlike Yeltsin, Putin was young, healthy, sober — and popular.

Under Putin’s first two terms, Russia started getting richer and more powerful, fast. The threat shifted from a potential Lukashenko populist takeover of Russia-Belarus, to Russia swallowing up Belarus and Lukashenko with it.

The two countries needed each other and professed public love for each other, and each had a lot to offer: Russia offered Belarus subsidized fossil fuels and a large market for Belarussian exports; Belarus could provide a military and political bulwark against NATO, which was expanding eastward to Russia’s borders. The one thing the Kremlin could not allow was losing Belarus to NATO.

In practice, this meant Lukashenko’s best policy was maintaining as much Belorussian independence as possible, while squeezing Russia of all the subsidized economic benefits it could. “Da, da! Of course Brother Russia, we’ll become one with you any day now, just keep that cheap oil’n’gas flowing and it’ll happen, we swear!” That meant Luk talked the confederation talk, and allowed a certain level of military cooperation inside Belarus so long as it wasn’t too threatening… but it also meant Russian power, including Russian “oligarchs” (as Russian billionaires are called), out of Minsk.

As commodities like oil and gas prices soared in the first decade of the 2000s, the Kremlin became increasingly annoyed with Lukashenko’s game. Things first came to a head in 2004, when Gazprom tried raising prices on natural gas to Belarus — the new price was still way below-market, but higher than it had been — and demanded control over the Belorussian portion of the Yamal-Europe gas pipeline (which brought gas from Russia’s gas fields in western Siberia to European customers in Germany and elsewhere).

Belarus refused to pay more for Russian gas claiming it couldn’t afford it, so Gazprom did what your local utility would do and cut gas supplies to Belarus. But Belarus decided to play hardball, and tapped (ie, stole) gas from the Yamal pipeline, gas that was meant for Russia’s customers in Germany and the Netherlands. That meant war — you used to hear a lot about Russia’s gas wars with Ukraine and other countries not in Russia’s direct orbit, but its gas wars with Belarus were legend. Gazprom escalated by shutting down the entire pipeline in February 2004 — no gas for anybody, Belarus or Europe. It took just a day of shutting down the gas pipeline to break Lukashenko and force him to agree to the new higher prices — and to selling control over Belarus’s portion of the pipeline to Gazprom.

Ironically, this first gas dispute between Russia and Belarus played a big role in accelerating the Nord Stream-1 gas pipeline project directly linking up Russia and Germany, as a way to protect them from Lukashenko’s whims.

In 2006, Lukashenko held a rigged election in which he supposedly won 84% of the vote. It’s not that he wasn’t more or less popular — but it wasn’t like he was going to allow a fair and free test of his popularity, at least as far as the West’s rules go.

2006 was the peak era of Washington’s color revolutions. Over the previous 3 years, there was the Rose Revolution (Georgia, 2003), Orange Revolution (Ukraine, 2004), and Tulip Revolution (Kyrgyzstan, 2005), all backed by the West and our good friends at the National Endowment for Democracy. Belarus had its own branded color revolution movement in 2006, the unfortunate-named “Jeans Revolution.” Lukashenko quickly crushed the “Jeans Revolution” protests, sparking sanctions by the EU and US on Belarus, including a visa travel ban on the Batka (“big daddy”) Lukashenko himself.

Putin, on the other hand, supported Lukashenko’s election win, however rigged, and his stomping of the ”Jeans revolution.” You really have to wonder who thought that name up, “jeans revolution” — is anyone really surprised it flopped?

Problems between Putin and Luk heated up again early 2007, when they were locked in another fossil fuel price spat — this time it was an oil war. Cheap natural gas was important for Belarussian energy (and transit fees), but cheap below-market Russian oil was used for Belarus’s lucrative oil refinery industry, which Belarus exported at world market prices and pocketed the difference. Which was a hefty profit, considering how quickly oil prices were rising during Dubya-Cheney’s wretched reign.

So Russia doubled the price of the oil it sold to Belarus, and raised its export tax on oil that passed through Belarus to Europe via the Druzhba oil pipeline, effectively slashing Belarus’s take even further. Belarus responded by charging Russia more to transit its oil through Belarus, and by stealing more Russian oil from the pipeline, leading again to a full cutoff of Russian oil supplies, screaming from EU customers, and Belarus quickly caving, again.

In 2008, relations between the US and Belarus went downhill fast when a top US embassy official attended anti-Lukashenko protests, and Belarus responded by expelling 10 US diplomats. Since 2008 up through to today, there has been no US Ambassador in Belarus, and almost no US-Belarus diplomatic relations to speak of (as you’ll see, that almost changed in 2018-20).

However, later in 2008, Lukashenko’s relations with the West warmed a bit. That summer, Georgia got stomped by Russia after it tried seizing South Ossetia. To the surprise of some western observers, Lukashenko wasn’t happy about the whole Russia-stomping-its-neighbor thing. It wasn’t that Lukashenko supported Georgia, it was just frightening to behold on a visceral level. Which probably explains why Lukashenko refused Russia’s request that Belarus recognize the breakaway statelets South Ossetia and Abkhazia — and for this, the EU rewarded Belarus by easing some sanctions.

By 2008, Putin was no longer president of Russia, and a lot of foreign policy knuckleheads in Washington and Brussels thought they could cleverly peel softer, more “liberal” parts of the Russian world away – the “liberal” president Medvedev from “hard-line” PM Putin; Belarus from Russia, and so on.

Starting in 2010, these tensions started to heat up. Lukashenko was due to hand himself another rigged landslide election at the end of 2010. He was already squabbling with Moscow about a new round of price hikes for Russian oil and gas. The Kremlin had grown sick of Lukashenko’s games — pretending to be Russia’s eternal little brother to keep the subsidies rolling, while at the same time fiercely guarding Belarus’s sovereignty.

Russian state television, which beamed into Belarus, savaged Lukashenko and openly courted the leading opposition candidate for the 2010 election. There was even talk of Russia prepping its own version of a color revolution to get rid of Lukashenko once and for all and install a friendlier regime. As Der Spiegel wrote that year,

“Ahead of [2010] presidential elections in Belarus, Moscow has subjected the incumbent Lukashenko to a series of attacks in the media and is preparing to strongly intervene in its neighbor’s election campaign. Ironically enough, it could end up being Russia’s leadership — not normally known for a love of democracy — that help[s] bring about the downfall of the man commonly referred to as Europe’s last dictator.”

The number 80 must be Luk’s lucky number, because once again Lukashenko claimed he won 80% of the vote in the December 2010 election. Protests broke out in Minsk, which turned out to be a lot larger and more organized than anyone expected. The West wasn’t exactly happy about those protests — it had spent much of 2010 courting the Belarussian dictator, sensing a possible opening from the worsening relations with Russia. The bare minimum that the West asked of Lukashenko was to be a bit more moderate about his election theft — don’t steal the elections too crudely, and please for gods sakes don’t crack too many protesters’ skulls, so that we, the human rights loving West, can continue cleverly peeling you away from our rival Russia.

But Lukashenko couldn’t help himself: the police crackdown, caught on camera and shown on TV news all over the world, was too gory to ignore. So once again relations with the West cooled, and Russia and Lukashenko were besties once more. Back-and-forth, back-and-forth, only this familiar pendulum swing only accelerates.

A New York Times article on the brutal crackdown captures some of these tensions:

“Antigovernment protesters were beaten back by swarms of riot police officers on Sunday when they tried to storm the Belarus government headquarters here in an outburst of anger and frustration over the apparent and, many said, wholly unsurprising re-election of the country’s authoritarian president, Aleksandr G. Lukashenko.

“…A reporter and a photographer for The New York Times were among those who were beaten, but they were not seriously injured. The police slammed people to the ground and held them there for several minutes, pushing their heads into the snow, before suddenly leaving.

“…The rising tensions on election night belied a concerted attempt by Mr. Lukashenko to make these elections appear more democratic in an effort to get money from the West as relations with his longtime patron, the Kremlin, have declined.

“Many Western countries, particularly in the European Union, have appeared heartened by these developments, and have sought to engage Mr. Lukashenko. Poland and Germany recently offered Belarus $3.5 billion in aid if this election was deemed free and fair.”

Lukashenko’s double-game with Russia also carried over to the economic sector, where he went medieval if necessary to keep powerful Kremlin-connected business interests off of his turf. A good example of this was the so-called Baumgertner Case: In 2013, a cartel deal between Russia’s Uralkili — one of the world’s largest potash fertilizer producers — and Belarus’s counterpart, Belaruskali, fell apart, leaving the Belarusian partner in a desperate commercial position. So Lukashenko set a trap to force the Russian potash “oligarch” to back off: Belarus’s prime minister invited Uraliki’s CEO, Vladislav Baumgertner, to Minsk for negotiations. When those negotiations didn’t go Belarus’s way, they did what Lukashenko does to everyone he dislikes: threw Uralkili’s CEO in jail, accusing Russia of trying to dominate Belarus’s key fertilizer-agriculture industry. Belarus also put out an international warrant for Russian billionaire “oligarch” Selim Kerimov’s arrest (Kerimov was one of Uralkili’s largest shareholders at the time).

Kerimov was never arrested by Lukashenko, but Uraliki’s Russian CEO, Baumgertner, wound up spending over a year in a Belarussian jail before being released on bail. That was how Lukashenko negotiated with his closest friend and ally. It was never a smooth relationship.

Then came the Maidan protests & coup in 2014, followed quickly by Russia illegally annexing Crimea and supporting Donbas separatists in the breakaway Luhansk and Donetsk republics. You might think that Lukashenko would’ve been most bothered by the way western-backed protesters violently overthrew Ukraine’s democratically elected Russia-friendly president, Viktor Yanukovych. But that’s not quite how Lukashenko saw it. The Batka may not have liked the Maidan coup, but he was arguably more threatened by Russia breaking taboo and seizing Crimea, a weaker neighbor’s territory. It reminded him how precarious his own hold on power could be, especially since he couldn’t turn to NATO the way Ukraine seemed to be able to.

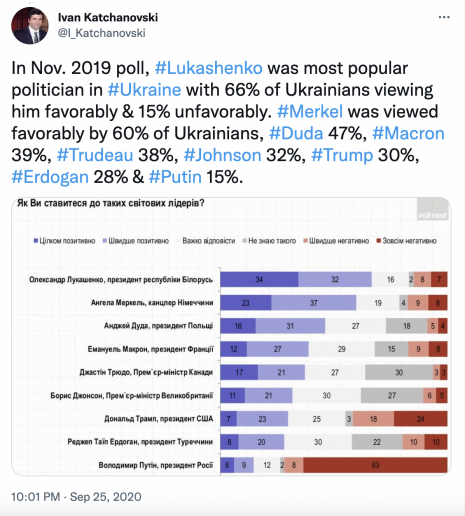

So Lukashenko surprised everyone by refusing to recognize Russia’s annexation of Crimea. That made him an instant darling in both Europe and especially in Ukraine, where polls showed Lukashenko became a hero for his stand against Russian imperialism. As late as 2019, a Ukraine poll named Lukashenko the most popular foreign leader.

The chaos that consumed Ukraine following the Maidan coup, plus the subsequent Russian invasion, also helped Lukasheno’s popularity at home. Luk brought stability and better standards of living; Ukraine and its color revolutions only brought chaos and violence.

It was Lukashenko’s independent stand on the 2014 conflict that positioned him to play the great mediator between Russia and Ukraine, along with Germany and France, in the peace talks known as the Minsk Accords.

By 2015, the West was really accelerating its play for Belarus. Luk won yet another rigged landslide election in October, registering 84% of the vote, and to the relief of NATOland, there were few protests and few cracked skulls to ruin PR efforts to rebrand Lukashenko as a potential maverick ally of the famously-humanitarian West.

Meanwhile, Belarus was also gumming up the works on Russia’s plans to build an airbase in Belarus.

Delighted with these anti-Russian moves from Minsk, both the EU and the Obama Admin softened their sanctions against Lukashenko — once again making a play to peel off Belarus.

From 2015-20, relations between Lukashenko and Putin went downhill fast. In 2018 Lukashenko appointed a new government stacked with so-called “market reformers” (read: western-friendly) led by prime minister Sergei Rumas and his new finance minister, Maxim Yermalovich.

Russia responded to this by naming a close security services ally of Putin’s, Mikhail Babich, ambassador to Belarus. Belarus was signaling that it was ready to step up the playing-both-sides game; whereas Russia, by appointing a scary silovik like Babich as its envoy to Belarus, was letting Lukashenko know it was done playing his game. Babich had previously served as Putin’s viceroy in Chechnya early in the Second Chechen War, and later Babich served as the Kremlin overseer (plenipotentiary) of the Volga Region as part of Putin’s “vertical power” structure. After the Maidan coup, Putin tried namimg Babich as Russia’s ambassador to Kyiv, but Ukraine refused to let him in and he never took up that post. So instead, in 2018, Babich took over the Russian Embassy in Minsk, where locals started referring to him as the “governor general.” Which is basically like calling him “The Viceroy.”

What Babich’s appointment to Minsk meant was that Putin was done playing Lukashenko’s game. The Kremlin was planning to bring that relationship to a head rather than waiting for a Maidan in Minsk.

Babich went to work putting the squeeze on. He publicly flaunted meetings with anti-Lukashenko opposition figures, and publicly criticized and mocked the Batka in media interviews.

Then Russia dropped a fresh economic bomb, announcing plans to end for good its oil and gas subsidies to Belarus. This wasn’t a mere tinkering with the subsidies levels as in years past, but more like a complete phase-out that would blow a hole in Belarus’s budget billions of dollars wide, and destroy the country’s vital refined-oil export industry. The squeeze was on.

Relations went from bad to worse, fast. In December 2018, Lukashenko and Putin were yelling at each other on live TV at a conference in St Petersburg. A couple months later, Lukashenko started publicly calling for closer ties between Belarus and NATO.

This opportunity was not going unnoticed in Washington, Brussels, or in the weapons industry’s ideas mill known as The Atlantic Council — where one A. Wess Mitchell, the top US State Dept official for Europe and Eurasian Affairs at the time, gave a speech in which he placed Belarus in the same exalted category as Ukraine and Georgia as key “frontier states” whose “national sovereignty and territorial integrity [offers] the surest bulwark against Russian neo-imperialism.” You hear a lot of blather these days about Russian colonialism and imperialism from DC and Brussels-linked think-tanks and academics, and from Ukraine’s point of view it’s very real. But here you have a top US official in the Empire naming Belarus as a “bulwark” against “Russian neo-imperialism” — to the applause of the Atlantic Council. To quote Michael Scott, my how the turntables have…t-…

As we’ll see, Secretary Mitchell wasn’t just spittin’ empty words. Within a year of his speech, in September 2019, Trump’s neocon psycho-at-large, John Bolton, made a high-profile visit to Belarus to lay the groundwork for the Big Peel-off. Bolton’s was the first such visit by a top-ranked US official to Belarus in over a decade. Things were moving fast.

A couple of weeks after Bolton went to Minsk for some weird happy photo ops with Lukasehnko, Russia publicly complained that their planned airbase in Belarus had been shot down for good, which Sergei Lavrov called “an unpleasant episode.”

Yes, this really happened just a few years ago

As you can see, this does not describe a Belarus that would host a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. They wouldn’t even host a frickin airbase!

And Lukashenko was just starting to flaunt his big new NATO friends. In a December 2019 interview with the liberal Russian radio outlet Ekho Moskvy, Lukashenko warned Russia to back off, or else there’d be trouble with NATO:

“If Russia tries to violate our sovereignty as some people say, you know how the global community will respond; they will be drawn into a war. The West and NATO won’t tolerate that because they would see it as a threat to themselves. In that sense, they would be right.”

Lukashenko was scrambling around for an out — how could he maintain dictatorial power without getting swallowed up by one of the two big mafias: the West with its “democracy promotion” machine, or Russia’s overwhelming military-economic power from the east?

Russia wanted to force Lukashenko to finally shit or get off the pot about integration with Russia — no more playing the two-sides game! The Kremlin made it explicit both in public and private that if Belarus wanted to keep those all-important Russian subsidies coming, it would have to agree once and for all to real integration: a single currency, a single political supra-government integrating the two countries. No more cake & eating it for Luk.

As 2020 began, Lukashenko scrambled hard to keep his options open, which in practice meant accelerating his rapprochement with Washington and Brussels.

In January, his defense chief publicly called for closer ties with NATO. And in February, Secretary of State Pompeo visited Belarus, chumming it up with the dictator and pledging first-ever US crude oil shipments to wean Belarus off Russia.

2020: Year of the Neocon Bromance

2020: Year of the Neocon Bromance

The first US crude shipments reached Belarus in May, just as Washington announced it was reestablishing relations by sending its first ambassador to Belarus since 2008 — a bigwig foreign service officer, Julie Fisher, who has spent much of her career moving back and forth between high level jobs in the State Department and in NATO headquarters.

And in case it seems counterintuitive today to imagine that Lukashenko really thought he could’ve been saved by NATO, all he had to do was look to the example of Montenegro’s notorious mob boss/dictator-for-life, Milo Djukanovic. Let’s take a minute to look at the Montenegran autocrat’s example here. Djukanovic has been ruling Montenegro since 1991, even longer than Lukashenko has been ruling Belarus. Djukanovic has a rap record in the West, and was even named “Person Of The Year In Organized Crime and Corruption” by the OCCRP. In the 1990s, he was facing the Hague for his support of Milosevic’s wars. But he flipped. And as soon as Djukanovic made good with NATO, all of his sins were magically washed away as his reward for ditching America’s official enemies, Russia and Serbia.

Montenegrin autocrat Djukanovic: from western villain…

…to Made Man in the NATO Mafia

In 2017, Djukanovic positioned himself as a victim of Russian and Serbian conspiracies to overthrow the tiny coastal country’s pseudo-democracy. While playing victim to Russia, he engineered a highly controversial (ie, rigged) vote to bring Montenegro into the warm embrace of NATO, and voila! No one talks about Djukanovic’s litany of crimes and human rights violations anymore — to do so would only play into the Kremlin’s hands, donchaknow! He’s a made member of The DC Cartel, the only mafia family that matters!

So Lukashenko could look to Montenegro’s corrupt autocrat-for-life as a clear example of the rewards he could expect if he flipped for good and delivered Belarus to NATO.

But first, Luk would have to deal with another round of Belarussian elections, scheduled for August 2020. His popularity had been falling since he stole the 2015 election — Belarus’s economy had stagnated and sagged alongside its patron Russia’s economy. And people, especially young people, were just getting sick of him. That’s the problem with autocrats who stick around too long — people don’t like seeing the same face over and over, makes it too easy to project all their failures and problems on that one face. This is one of the devious strengths of our system of oligarchy-with-democratic-trappings: keep changing those hominid faces up front, and the rest of the chimps won’t have time to work up enough organized hate, they’ll slash each other’s throats instead while dreaming big dreams about the next hominid face to pin their hopes and hates on. And Lukashenko’s notorious human rights record didn’t help endear him, especially among youngs and urban professionals.

Meanwhile, frontline NATO countries and Washington had been funding and training pro-democracy Belorussian activists as a Plan B in case Lukashenko didn’t flip. The West wasn’t putting all their chips on Lukashenko doing a Djukanovic turn, but they were pursuing that possibility with more energy than ever. If that failed, there was always the pro-western protesters for leverage.

Russia’s strategy to deal with Lukashenko was a bit more simple: squeeze Lukashenko’s economy to make him break; and support the leading opposition candidate against Lukashenko, a Gazprom-connected banker named Viktor Babariko, for leverage. It helped that polls put Russia’s candidate for the August 2020 elections ahead of Lukashenko by a pretty good margin, so Russia seemed to be in a good position to deal with a potential vassal-turncoat.

Lukashenko decided to take no chances. Elections are always a dangerous time, and you need people you can rely on. So he fired his “pro-market reformist” prime minister and government, and replaced them with Belarussian siloviki, security-services loyalists who wouldn’t flinch if they needed to get rough. But it wasn’t Western “democracy” that Lukashenko feared most. In 2020, his paranoia was mostly focused on the Russia threat.

In late June, just weeks before the election, he arrested his biggest election threat— the Kremlin-backed candidate, Babariko — and publicly accused Russia of “election meddling”. Soon afterwards, Lukashenko started rounding up all the other opposition candidates to make sure they couldn’t challenge him in August either, including blogger Sergei Tikhanovsky, whose wife, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, was allowed to run in his place (apparently Lukashenko, an old-school macho boss, thought running against Tikhanovksy’s nobody wife would be a hoot, giving him an easy election victory while keeping the Nato dogs at bay).

As things were coming to a climax, Lukashenko was developing nicely into a pro-Western transformation-of-character hero. A month before the election, the New York Times was running articles about Lukashenko’s heroic turn against Russia.

Then came the scandal that would later be known as Wagnergate.

I won’t get too deep into the weeds of Wagnergate, so here’s a quick summary: in July 2020, just weeks before the election, Belarus authorities discovered that dozens of Russian mercenaries from the notorious Wagner Group had mysteriously gathered in a third-rate sanitarium outside Minsk. Lukashenko had them all rounded up, jailed and tortured — he assumed that this was the thing he feared most, the dreaded Russian coup plot come to finally get him.

In reality, the Wagner mercenaries had been lured to Minsk by a joint CIA-Ukrainian military intelligence operation to kidnap and put on trial suspected Russian war criminals from the battles in the Donbas in 2014-15. The Ukrainians and their CIA advisors set a trap, promising the Russian mercenaries work in Venezuela, which they’d reach using a chartered jet from Minsk to Istanbul to Caracas. According to the original plan, once the chartered jet full of Russian mercenaries flew out of Belarus airspace and over Ukrainian airspace, Ukraine air force fighters would intercept it, force it to land in Ukraine, and put them all on public trial, scoring propaganda points and exposing Russian crimes. (Not to mention provoking Russia, a major goal of the time.)

But the CIA-Ukraine plan fell apart when already-jittery Belorussian authorities got wind that a bunch of shady Russian mercs, 33 in all, had mysteriously sneaked into Belarus for reasons the Belorussian KGB could only fathom, and assumed the worst. (Over the next year and a half, Wagnergate morphed into a major Ukrainian political scandal in its own right — President Zelensky claimed he was left in the dark about the original plan, and he accused those who cooked up the whole plan, mainly rivals within Ukraine’s military-intelligence structures, of using the Wagner conspiracy to plot a coup against Zelensky himself. Like I said, too much to get into here, just know that the plot Lukashenko thwarted had legs of its own in Kyiv, stretching to Langley, and we’ll probably never know the full truth…)

Russia, of course, denied that the arrested Wagner mercenaries were part of a coup plot — in fact Russia had no idea what was going on at all. At first, Lukashenko didn’t believe the Kremlin. He had good reason to be suspicious. Midsummer 2020, when the Wagnergate scandal broke, was the low point in Belarus-Russia relations. As Russia tried to get to the bottom of the Wagnergate plot and demanded answers from Belarus, Lukashenko publicly accused Russia of “lying” and sent Belorussian troops to the border with Russia, fearing an all-out invasion.

But then over the early weeks of August, everything quickly broke and flipped the other way. First, the Belorussian elections took place and once again Luk awarded himself 80% of the vote. That sparked massive anti-Lukashenko demonstrations that couldn’t be bottled up as they had been in 2015 and 2010. As the protests spread and the westerners he thought were his new friends quickly started to abandon him, Lukashenko’s intelligence officers discovered, probably via torture, that the Wagner Group mercenaries had not been sent to Minsk to overthrow him. Instead they were marks in a covert CIA-Ukraine operation.

Between western-backed democracy activists on the streets calling for Luk’s overthrow, and a CIA-led operation that brought 33 Russian mercenaries into Minsk, the Lukashenko very quickly reassessed where the real threat to his rule lay, and how cornered he really was after giving the finger to Putin over the previous couple of years.

At first, it seems Washington was caught off guard by the sheer scale of the anti-Lukashenko protests. Many of the apparatchiks in DC were still too invested in their strategy of peeling Lukashenko away from Russia. This confusion was captured in a CNN article three days into the protests headlined, “Major US diplomatic push to counter Russia may be in jeopardy amid Belarus unrest”. The split among Washington foreign policy elites was aired by two leading DC think-tanks — the Atlantic Council, whose deputy director Melinda Haring told CNN that Pompeo should continue with the diplomatic rapprochement: versus the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) called that strategy “dead.”

The protests were too large and too sustained and Lukashenko’s crackdown was too brutal — and it was all headlined too often in the western media — to continue trying the realpolitik strategy pursued by Pompeo and backed by the Atlantic Council. As the protests grew in size and strength, the EU and US hit Belarus with sanctions and unified behind the regime-change protest movement. Whereas Russia opposed the overthrow of Lukashenko, but stayed on the sidelines, waiting for Luk to get desperate enough to come begging Putin for help.

Five days into the protests, Lukashenko freed the Wagner mercenaries and said they’d all been deceived by NATO and Ukraine. His rule looked shaky; the Belorussian public, usually passive, was not standing down. The protests were growing in numbers, no matter what the authorities tried doing. For a while in the early autumn of 2020, the smart money was on Lukashenko going the way of Yanukovych…or Ceaucescu. And Putin didn’t rush to Lukashenko’s aid right away. He waited for Lukashenko to reach maximum desperation to cut the best deal possible for the Kremlin.

Finally, Lukashenko broke. He had no choice: as more sectors of the country abandoned his regime, he knew he could not survive, quite literally survive, without Russian help. But this time, for Putin, there would be no more games, no more fucking around. The days of Lukashenko yammering about Belarussian sovereignty and playing NATO off against Russia were over. A month into the protests, Lukashenko flew to Russia to publicly supplicate.

(Top) Lukashenko in 2019 wagging his sovereignty-finger at Putin for the cameras, and for his NATO friends;

(Bottom) Lukashenko in September 2020 sweating bullets as he signs over the family business to Putin in exchange for protection.

Eventually, as the protests continued into September and October 2020, Putin offered Lukashenko more and more support to keep his regime in power — everything from intelligence and policing support to massive loans. The price for Lukashenko surviving has been the end of Belarus’s sovereignty as he knew it for 26 years: no more playing NATO off against Russia, no more dithering about Russian airbases, no more jailing Russian oligarchs. Instead, Lukashenko had to agree to pro quo the biggest favor of all, one that was unthinkable all those years past: letting Russia use Belarus as a doormat into Ukraine.

“Vova, babe, did I say you can’t have an airbase? What I meant was, you can have the whole country!”

As we’ve discussed in RWN, another major political shift happened in the fall of 2020, just as Lukashenko was at Putin’s feet: Ukraine’s president Zelensky, the one-time “peace with Russia” candidate,” made a giant u-turn and was now going all-in with Ukraine’s nationalist hawks and the NATO crowd for maximum confrontation with Russia. Zelensky’s change was coordinated in Washington with people from the incoming Biden Administration and the neocons at the Atlantic Council.

So when 2021 came around, and Putin saw that the new Biden administration was determined to step up NATO integration with Ukraine and take a harder approach against Russia, Putin saw he had a rare opportunity to use Belarus however he wanted now that Lukashenko owed him his life. For Putin, this meant a rare chance to hit the heart of Ukraine from the Belarus border, just north of the prize target, Kyiv. It was an opportunity that wouldn’t last forever, maybe a year or a few years at most, given the ferocity of anti-Lukashenko protests and the mercurial nature of Lukashenko himself. If Putin waited, Lukashenko could fall, fortunes could change, Lukashenko could return to his sly old ways. Either take advantage of this moment where you can strike at Kyiv from Belarus, or lose it forever.

Bold isn’t always smart, as we know. Bold can be really really stupid. Don’t do bold, kids, would be my advice, but as they say in Russia, “He who doesn’t take risks doesn’t drink champagne.”

So thanks to the failure of Belarus’s western-backed regime-change movement in the summer-fall of 2020, Putin finally had a window of opportunity to do something really stupid: Launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine centered on subduing Kyiv and forcing into power a friendlier more amenable regime. It didn’t work, but if Ukraine’s leaders are to be believed today, Russia is on the verge of launching another invasion from Belarus any day now.

Subscribe to the Radio War Nerd podcast & newsletter!

January 23rd, 2023 | Comments (2)